Ears of the People

Smithsonian Folkways Announces First Full-Length Album of Senegalese Ekonting Music,

The Ekonting is the key ancestor of the American banjo, but this album shows it’s also a remarkably vibrant instrument in the hands of the Jola of Senegal and the Gambia, tied to wrestling ceremonies and songs of village life

The Ekonting is the key ancestor of the American banjo, but this album shows it’s also a remarkably vibrant instrument in the hands of the Jola of Senegal and the Gambia, tied to wrestling ceremonies and songs of village life

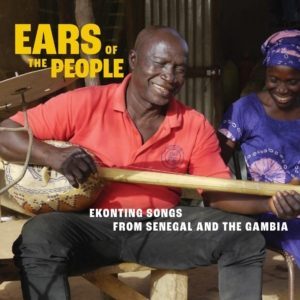

The first album of West African ekonting music, Ears of the People: Ekonting Songs from Senegal and Gambia is a testament to the endurance of music and tradition across the gulf of centuries and some of the most brutal history imaginable. It’s also a showcase for living traditions in West Africa, and for the wealth of stories and beauty that a humble, handmade instrument can hold. Though it’s generally acknowledged today that the American banjo came originally from Africa and should be considered an African instrument, for many years the question remained as to what African instrument exactly was the source of the banjo? Scholars, including Pete Seeger, pointed to instruments like the Wolof xalam or the Mandinka ngoni as possible antecedents, but it took the work of pioneering Gambian ethnomusicologist Daniel Laemou-Ahuma Jatta (who also wrote the album’s foreword) to show the Senegalese and Gambian ekonting (also spelled “akonting”) as a particularly likely source. In the evening, after work, Jatta’s father played this three-stringed, gourd instrument popular among the Jola people.

Ekonting player Jules Diatta earned the nickname “Ekona” (meaning “wrestler”) from his youthful wrestling prowess, which brought him all the way to national wrestling competitions in Dakar. Today, he lives in the adobe house where he grew up in the village of Mlomp. He farms rice, harvests palm wine, and leads the ensemble Sijam Bukan, meaning “Ears of the People.” The group is a flexible collection of friends and neighbors: Ekona sings lead vocals and plays ekonting, David Manga plays tumba drums, Prosper Diatta taps spoons on an iron pot, Marie-Claude Sarr and Diankelle Senghor clap palm leaf stems called uleau, and Gilbert Sambou leads a chorus of singers and dancers sucked in by his contagious enthusiasm.

Music accompanies every stage of a Jola wrestling match. Young wrestlers strut their way to the center of the village backed by a parade of supporters singing their praises. There, they join a ring of other wrestlers dancing around the large slit log drum called bombolong or ekonkon, which is the word for both wrestling itself and the accompanying dance. (It also shares the common linguistic root kon, meaning “to knock” or “to strike,” with the ekonting.) Stomping up clouds of dust, they brandish swords, spears, and flags to ramp up their excitement. After the match ends, ekonting players from different neighborhoods may face off in competitions of their own. They do so at their own risk: the loser’s ekonting may be smashed to pieces by the superior player.

This song, “Mamba Sambou” is typical of wrestling songs: short and lively, with pithy lyrics using vocables (such as oh, ay, and ee) that make it easy for the whole crowd to join in. Other songs use stock phrases like ekondoorool mang (“his neck is made of iron”) or busolool bugoliit tetam (“his back never touches the ground”). In this case, Sijam Bukan alternates between the name of their wrestling champ, Mamba Sambou, and the leader of their ensemble.

Ears of the People

Smithsonian Folkways Announces First Full-Length Album of Senegalese Ekonting Music,