REMEMBERING GUY CLARK

Remembering Guy Clark:

Goodbye to a Great One You Never Knew

Guy Clark, an unquestionably influential artist, has left us. Johnny Cash was the first to record one of his songs. Next, Bobby Bare made the top-40 with another. All en-route to a number-one by Ricky Scaggs with a third. There were more. And it wasn’t just his writing. He received two Grammy nominations for albums of his own, and there was a Grammy nom for the two-disc tribute by lots of big names singing from his deep catalog of originals.

Guy Clark, an unquestionably influential artist, has left us. Johnny Cash was the first to record one of his songs. Next, Bobby Bare made the top-40 with another. All en-route to a number-one by Ricky Scaggs with a third. There were more. And it wasn’t just his writing. He received two Grammy nominations for albums of his own, and there was a Grammy nom for the two-disc tribute by lots of big names singing from his deep catalog of originals.

I interviewed him twice, once for print, once on live radio, where he sang with his guitar and longtime side man Verlon Thompson, and rang the phones off the wall. Both occasions were truly memorable. We’ll get to that.

“His songs were recorded by Johnny Cash, Ricky Skaggs, Rodney Crowell, Emmylou Harris, Vince Gill, Brad Paisley, Alan Jackson, George Strait, Bobby Bare, Jimmy Buffett, Kenny Chesney, Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson and legions of others,” notes one writer.

His songs celebrated the struggles of life in our time, especially those of the working class, they grasp the universality of bittersweet thoughts of love and lost times and those still hoped for, all the way to the simple joys of eating what you can grow in your own garden. There is always a freshness to a Guy Clark song.

Folkies still love singing his decades-old Homegrown Tomatoes, recorded and sung on big concert tours by everyone from John Denver to John Prine. And we could have cited a dozen similar examples of other artists doing the same with his other songs.

If you don’t know Guy Clark’s name, you should. Your life will be better for discovering his music.

Don’t bother with the so-called “entertainment news” today. You aren’t likely to find coverage of his legacy or, for that matter, of any respected artist there who is vibrantly working or recently dead and immediately missed. Not there, where they’ve never been featured amidst the drivel of the self-aggrandizing, excruciating annoying, inscrutably pampered famous-for-being-famous, whose tantrums, pet monkeys, my-publicist-says-it’s-time-for-some-bad-behavior, practitioners of wholly artless antics who own that turf for absolutely no justifiable reason.

Let’s talk about a real artist.

Like Desperadoes Waiting for a Train, a beloved Willie Nelson – Kris Kristofferson hit, was a Guy Clark song. It originally debuted on Clark’s first album in 1975 when he was a 34-year-old performing songwriter who looked impossibly young compared to how most of us envision him. It was one of so very, very many songs from his albums of originals that others would also record and propel. “L.A. Freeway” was another. We’ll get to more, including some that rode into lofty places on the charts.

And mentioning the music charts reminds me of a second meaning of the word, because Guy Clark did his writing on graph paper, longhand.

That’s one of the bits I must organize from the Gestaltic flood of so much about him that comes with learning of his passing.

In and out of major news sources last night, I suddenly encountered and immediately read the sad news of the death of Guy Clark and immediately thought, “No, not him. Not this kind of news again. Not such a great and greatly influential musician. Not that gruff ol’ folkie who had been so generous to me with his time, so willing to exchange thoughts.” It was a bit later that I realized the trust it represented that he had done that sharing and not taken the opportunities he was given to ease me out.

Last night, I had been otherwise occupied with the results of the Oregon and Kentucky Democratic primaries, focused on Bernie Sanders and whether America was more or less likely to achieve that future we can believe in.

But Guy Clark was dead. Someone whose music and outlook was expressed so lyrically through his prolific catalog of originals. And it was all there, derailing something else, as his music was always able to do. Through good times and bad — for me, for him, for those he knew and plenty he didn’t — for the history and culture and events of the times. And through plenty of select songs penned by others to which he imparted deeper meaning than the original versions.

All of it just brings anything else you’re doing to a complete halt.

Early this morning, I found a late-night message from a friend in politics and music who must have felt very much the same thing.

That message read:

“Guy Clark November 6, 1941 – May 17, 2016

That dash held a lot of life and love and music.”

Then, some quoted lyrics:

‘Oh Susanna, don’t you cry, babe

Love’s a gift that’s surely handmade

We’ve got something to believe in

Don’t you think it’s time we’re leaving’

“Thanks for the music and the memories, Guy. We will miss you.

“Rest his soul.”

Indeed. Those lyrics are a tribute to his wife, who died in 2012. She was hugely important as the love of his life and source of inspiration. Both of them were painters whose work included front-cover album art for iconic musicians.

Guy and wife Susanna “were ringleaders in a Nashville roots music circus that included luminaries,” notes the Nashville “Tennessean,” a force that includes Emmylou Harris, Rodney Crowell, Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, Mickey Newbury, Billy Joe Shaver, and so many more.

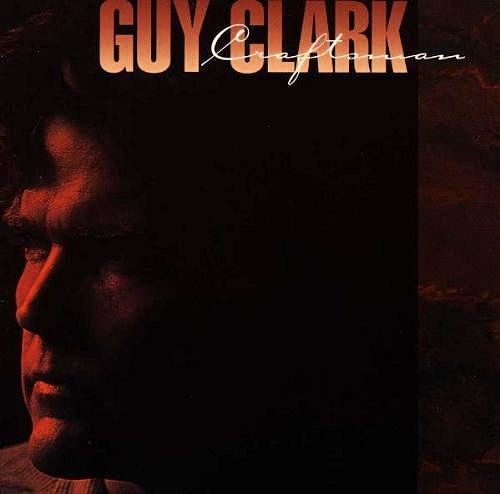

“The patron saint of an entire generation of bohemian pickers, Guy Clark has become an emblem of artistic integrity, quiet dignity and simple truth,” wrote Robert K. Oermann more than two decades ago for the liner notes in Clark’s 1995 Craftsman CD.

“The patron saint of an entire generation of bohemian pickers, Guy Clark has become an emblem of artistic integrity, quiet dignity and simple truth,” wrote Robert K. Oermann more than two decades ago for the liner notes in Clark’s 1995 Craftsman CD.

Into recent years and even as his health failed, Guy Clark’s world was an amazing mix of interacting with the energetic innovative now of young songwriters and keeping the past vital and alive. For decades, Guy Clark did so very much to make sure the musical legacy of Townes Van Zandt continued to be played and talked about and recorded and heard. Townes was Guy’s closest friend, and “T’ooow-enns,” as Guy sometimes drawled for effect, had died way too early.

The most known Townes Van Zandt song, If I Needed You, was one he wrote in the spare bedroom of the Clarks’ home on Chapel Avenue in East Nashville. Guy and Susanna were great pals of Townes seen together in Music City venues.

Later there was similar esteem expressed on stage by Guy in his adoption of the songs of Verlon Thompson.

Guy didn’t need to do anything for either Townes Van Zandt or Thompson, since his own superb songwriting brought so many top artists to record HIS songs. Plus, his strong performance ability, which in later years included anecdotes, banter and stories that brought favorable comparisons to Mark Twain — were enough to take him to any stage, anywhere.

He was, indeed, the soul of that entire Golden Age of Texas-based rootsy folk music, when Austin was the center of gravity. Even though he was based in Nashville for four decades, influencing a generation of artists and writers there.

His first album “was received really well, right from the start,” he told The Nashville “Tennessean” newspaper in 2009. He noted, “I got this great review in ‘Playboy,’ and Willie Nelson’s ‘Red Headed Stranger’ got kind of panned in that same issue.”

Writing yesterday, that newspaper’s Peter Cooper added, “History would protect the good name of ‘Red Headed Stranger,’ and it would also confirm Mr. Clark’s significant place in the songwriting continuum.”

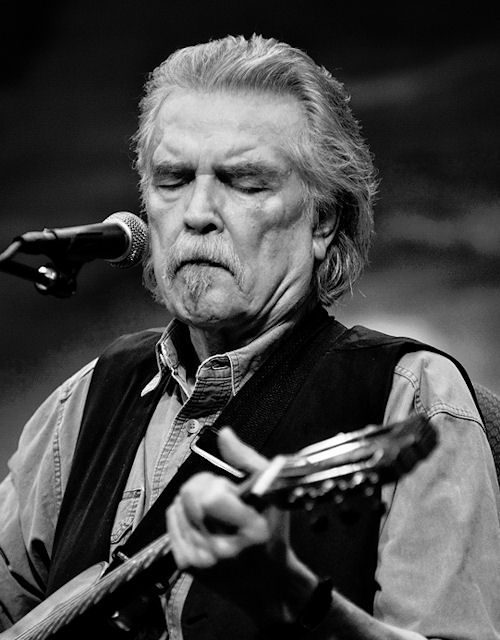

When he died yesterday he was only 74 — “only,” because he seemed to have always been there, and the effects of his infamously incessant smoking which gave him the cancer that eventually killed him — had, years earlier contributed to his weather-beaten appearance, famously gravelly singing (and speaking) voice, and skin that looked like desiccated old leather.

I remember shaking hands with him was a bit like a Brillo pad, but he gave you just the right amount of lingering grasp and focused eye contact so you knew he was focusing the moment on interacting with YOU.

That’s something every performer could learn — a true essence of making a fan or a music journalist or anyone else feel special, giving them a personally important memory that’s forever after involuntarily recalled, at any mention of his name or recorded note of his music.

Aside from translating to sales of concert tickets and CDs, it is the essentially fundamental stuff that propels that contextual fame based on musical prowess into the building blocks of music legend: making fans and sealing the deal, meaningfully, one at a time.

I got to interview him for over an hour in 2002, in the reasonably quiet backstage of a huge Canadian music festival. That interview ran in a long-extinct publication, and my reporter’s notebook was stolen a few years later with most everything else I owned. So all I have is memories. (Though I should go see if I ever quoted from or referenced it in the Acoustic Americana Music Guide, or in FolkWorks, or anywhere else with an archive.)

I just can’t compile a complete list of all who recorded his songs. A partial has to include Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, Kris Kristofferson, Johnny Cash, Ricky Skaggs, Rodney Crowell, Vince Gill, Brad Paisley, Alan Jackson, George Strait, Bobby Bare, Jimmy Buffett, Kenny Chesney, John Denver, John Prine, Mickey Newbury, Billy Joe Shaver — and surely that still omits some genuine luminaries.

When I was privileged to have him as a performance-interview guest on my “Tied to the Tracks” radio show in the late double-aughts, he performed his own Boats to Build and Homegrown Tomatoes, a couple of Townes Van Zandt songs, and a couple by Verlon Thompson.

I was sure he didn’t remember our hour-plus spent together in that 2002 interview in Canada, but he assured me he did, and that was why he wanted to do the radio show. That was more flattering than is obvious, because he had received so many journalists for interviews in his basement room at home where he built guitars and wrote his songs — longhand, on his ubiquitous graph paper.

Otherwise, I have abiding memories of that radio performance and our live on-air chat, which in no way diminish the time he so generously gave me backstage at that festival.

Just he and I, both times. In Canada, he chased out Thompson — twice — who came to rescue him after predetermined intervals. “No, no, I’m fine,” he had said, the second time adding, “I’m enjoying this,” all rather contrary to his gruff image.

Indeed, it was a widely-ranging conversation in which he both spoke my name and called me “pardner” several times — some in agreement, some as a challenge in the way you dialog when you care what someone else thinks. And of course, I have and treasure the memories of seeing him performing on those and even more occasions, including at the Stagecoach Festival in Indio.

I’m sure the “Austin City Limits” online video archive will get heavily trafficked today for the shows he did with them over the years.

And there is this: highly recommended, unusually thorough, it’s an obit tribute by Peter Cooper in the Nashville Tennessean. Do yourself a favor and go read it:

His song, That Old Time Feeling, begins:

That old time feeling

Goes sneaking down the hall

Like an old grey cat in winter

Keepin’ close to the wall.

The cat’s out, somewhere, probably fixated on a butterfly. Winter’s past. No need for sneaking or staying close to walls in the wind. But there’s plenty of that old time feeling.

Adios, Guy. Vaya con Dios. And if your old guitar is nowhere to be found, we’ll know where it’s gone.

You can read Larry’s Acoustic Americana Music Guide with its extensive descriptions of upcoming folk-Americana and acoustic renaissance performances, and its companion, the Acoustic Americana Music News; both are updated frequently. He contributes regularly to No Depression. Contact Larry at tiedtothetracks@hotmail.com.