Joel Rafael – Bringing Woody to the World and Back

in which we discuss Italian art, Spain, Okemah OK, co-writing with Woody Guthrie, defending the nameless, and how doing things leads to other things

I met Joel Rafael in person at the FAR-West 2023 music conference, where we commiserated over inadequate technology (the Conference App Which Shall Remain Nameless.) But he got my attention through Facebook with beautiful pictures of Bird-of-Paradise flowers, and a spectacular desert skyline.

I met Joel Rafael in person at the FAR-West 2023 music conference, where we commiserated over inadequate technology (the Conference App Which Shall Remain Nameless.) But he got my attention through Facebook with beautiful pictures of Bird-of-Paradise flowers, and a spectacular desert skyline.

Over the years I’ve become aware of Joel’s quiet but persistent presence in the Folk community, beginning with a story in which he couldn’t believe his song “Goldmine” was being played on the East Coast by some acoustic duo (Lowen & Navarro.) He’s like that in person, too: quiet, persistent. If he’s speaking, something important is being said.

Listen to his songs: they speak of unadvertised tragedies, from a man working in the fields to a train crash, to someone looking out of a sinkhole in the middle of a long committed relationship. Joel Rafael is a master of carefully-placed description: You know where you are, and how far the sun is sinking, because he’s painted a picture with words. Conversation reveals Joel’s attentiveness to what’s around him. And his footprints are all over FolkWorks: He wrote “Some Words On Woody Guthrie” and has been mentioned in several other articles, like “Ribbon of Highway – Jimmy LaFave Interview” by Terry Roland.

There’s an impression that this man is reclusive, a lone coyote, but every story he tells is punctuated with the name of someone else involved. He brings them all along with him.

Joel agreed to speak with me over Zoom. I wasn’t expecting the art that surrounds him in his work area. I was intrigued. So we started there.

Woody Guthrie portrait, Charles Banks Wilson

me: I’m looking at that picture over your shoulder.

JR: Let’s see… Charles Banks Wilson is the painter. And the original painting was commissioned by the Oklahoma State Historical Preservation Fund and dedicated at the Oklahoma State Capitol in July of 2004. This Republican congressman had requested a painting from Charles Banks Wilson. He’s a famous Oklahoma painter. There’s several paintings of his already hanging in the Capitol and they wanted to commission one more painting basically before he died.

He said, “I’ll do a commissioned painting. I don’t paint meadows with buffalo in them anymore, so whatever I paint, you just have to accept it. It’s up to me.”

And they said, “No, no, we just want one of your paintings.”

So he painted this, and then when he delivered it, he told them: “There’s two conditions. One is that it will always have to hang in a public area. It can’t be in some back room somewhere. And you can never paint the cigarette out of Woody’s mouth. You got to leave the cigarette in his mouth.”

So they had a dedication. A bunch of us went to the capitol – it was right during the festival – Arlo was there that year, and he sang “Pretty Boy Floyd” in the State Capitol of Oklahoma, which was kind of cool.

Me: That’s very cool. Until listening to Woodeye – and I’ve been really smitten with that CD for the past two days – I was never familiar with that song, “Pretty Boy Floyd.”

JR: Oh, really?

Me: yeah. I know.

Joel got up and brought me closer via camera to another angle of the room.

painting by Franco Ori

JR: Here’s another big painting… I played a festival in Italy around the same time as the centennial of Woody’s birthday, and the festival I was playing was called the Sarzana Acoustic Guitar Meeting, and it was mostly luthiers. But there were some performers there too, and they had me there because of my co-writes with Woody. They call it a fort, but it was basically like a castle, an ancient castle in Sarzana. I walked across the drawbridge – because literally there was a moat around it – across the drawbridge and into the main part of the castle.

It’s a big open kind of area, and that’s where they had the whole festival set up with chairs and the stage and everything. And all around the edges of the area were these paintings like this one hanging up: Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and the Woody Guthrie one this guy was painting. It wasn’t done yet – he was working on it. I was just in awe.

And then the promoter came walking up, and I said, “Wow, this is amazing. Is he selling these?”

And the promotor said yeah, he’s selling ‘em for 300 euro apiece.

(me, in my mind: That’s pretty cheap.)

JR: And I thought, well, that’s pretty cheap. Then the promoter said something in Italian to the painter, whose name is Franco Ori. And Franco Ori looks back at the promoter and says something in Italian, and then the promoter says, “He’ll sell you this one for 100 Euros since you’re the Woody Guthrie guy.” So of course I bought it.

Me: Oh, hell yeah. How did you get it home? (Folks, this painting is massive.)

JR: he finished it that day, and I was there for a couple of days, so it was dry by that night or the next day, so he took it off the frame and rolled it up for us.

We drove from Sarzana, Italy across Southern France to Spain where I had three shows. A friend that we stayed with in Southern France helped us send it home, and it got home the day after we did.

Big Woody in the Rafael home

Me: I had on my list to ask you about any overseas shows that were especially impactful.

JR: Well, I’ve been really fortunate. A lot of performers, it’s kind of a bucket list thing: “I wonder if I could go to Europe and perform.” The audiences are very receptive and they really like American folk music. Now I’ve been to Europe about 14 times. I’ve been to the Netherlands four times, Italy three times, the UK four times. I’ve been to Spain four times. And Northern Spain is my best stronghold over there.

me: I believe it. They’ve got such a reverence for music, for acoustic music, and for history.

JR: That time when we had the painting, we drove over to Spain from Italy in a rental car that we had to drop off in Oviedo, up in Asturias in the north of Spain. The guy who had agreed to book three shows for me picked us up, doesn’t speak any English, and I, at that time, spoke very little Spanish. Somehow we just connected. And the three shows were in Irish pubs.

me: I love the Spanish-Irish connection.

JR: It’s so great. The North Coast is right across the Atlantic. So the whole north of Spain is really different than the rest of Spain, Celtic influence and everything. But he invited me back the next year and was able to pay me enough to bring a couple of musicians with me.

A couple years after that, he invited me back again. I took John Inmon and Terry Ware with me that time. And then within a year or two after that, we had the pandemic and everything kind of got put on hold. He invited me in 2022, but it was too soon. I wasn’t ready to get on a plane yet. In 2023, he invited me. And at that point, I’m getting up in age. I’m going to be 76 in May.

I just felt like I couldn’t pull it off. My wife and I had both gone the times before, and the promoter and his wife had actually come over in the interim and spent a week with us; so we’re really good friends. They wanted us both to come, but we figured out that if I went alone, it would actually be profitable in a certain way. I wouldn’t make a lot of money, but I could pay for the whole trip and not come home empty-handed: If my wife Lauren stayed home, she could feed our cat, make sure everything got watered, take care of the place, that kind of thing. And she kind of didn’t want to go; she’d been three times. Finally I ended up booking this two and a half week trip to Spain. And it was a total success.

me: Wonderful.

JR: I’d really worked hard for the last couple of years on my Spanish. I’m not fluent, but I was so much more aware of everything, driving around. Every building, I knew what it was, what they were doing there. It was a very fulfilling trip. And that was just last year. So I’m hoping I’ll go again maybe one more time, we’ll see how it goes.

me: I made friends during pandemic with a Catalonian folk duo, Lauzeta, and I’ve always wanted to go to Morocco. So my bucket list trip would be to fly to Morocco, drive to Catalonia, and then fly home.

JR: I had one show in Catalonia that was near Barcelona, and at my shows, I’d prepare some things to say in Spanish. It really helps to endear yourself to the audience if you can try to reach out in their language and attach to their culture a little bit. But when we went to my show outside of Barcelona, on the advice of my promoter, we rewrote the things I was going to say in Catalan.

me: Oh, did you? Oh, good. My understanding is a lot of the Catalonians can speak Spanish, but love their language. To respect Catalonia – that’s big.

JR: It’s really a very interesting cultural mix of people in Spain, from the Basque country to Catalonia to Southern and Northern Spain. It’s just like every section of our own country is regionally kind of different culturally.

Me: It is. Now, you played the Kennedy Center also, correct?

JR: Yeah, I did. And I was just watching the news a little while ago, and they were reporting on Vance getting booed at the Kennedy Center, I guess yesterday. He showed up in the box seats, and the whole audience just booed him.

me: Oh, fantastic.

JR: It was viewed by some as unpatriotic, but it was probably the most patriotic thing you can imagine.

me: That’s what I’m saying.

JR: I did get to play there for the Woody Guthrie Centennial, and there were two people on the show that weren’t as well-known as some of the others. And that was myself and Jimmy LaFave.

me: I’ve not met him. I know about him.

JR: We both had been in the trenches for Woody for a long time, and when these concerts started to come down, these centennial concerts – which they did several in 2012 – we were included in some of ’em. But the big one was going to be at the Kennedy Center in October. And the powers that be, which was basically at that point the people from the Grammy Museum in conjunction with the Woody Guthrie Archives and Woody Guthrie publications, were understandably trying to get the biggest names they could. And so we had to really fight to get onto that show. But somehow Jimmy and I got on the show, so it ended up being what I call a Who’s Who and Who’s That of Folk Music. We were the “who’s that?”

me: Right? In 2012 I lived in DC and I actually considered going, but life didn’t work that way. I was almost there. So what steps did you take to help make sure you could be on that roster?

JR: Well, I had management at that time, and my manager had worked in conjunction with the Woody Guthrie Center and Woody Publications. And it was just basically kind of a lobbying thing from her, and us expressing our desire to be on the show. “We’d love to be there, and if we can help in any way…” And I was lucky, I was on the L.A. centennial concert, and I was on the Austin one and the Washington DC one; I think there were about five altogether throughout the year. There was one in Tulsa I wasn’t on, but Jimmy was on that one. I think Nora Guthrie probably had the final word on it, and I think she really wanted both me and Jimmy on the show, but it was more of a thing of trying to figure out if there would be enough name acts on the show to sell it, for balance. As it turned out, it sold out in 20 minutes.

me: That might be why I didn’t go. I would assume that the Guthrie Family Foundation knows who you are by now.

JR: Oh, yeah. I feel really fortunate to, well, to be in the co-write club.

Joel Rafael, Sarzana IT, photo by Lauren Rafael

me: Yeah. So how did that come about?

JR: Well, I kind of initiated it. I guess anybody could have done it. However, there’s a lot of different ways to go about something like that. I didn’t know Nora Guthrie at the time, but I knew Arlo – not well. We’d met, and this was back when the Woody festival first started in 1998. That was the year that the Billy Bragg and Wilco Mermaid Avenue album came out. And Billy Bragg actually came to the first festival for the Wednesday show. And so there was kind of a buzz around that album and the whole idea that some of Woody’s unfinished songs were being handed out to some people.

I had been, at that point, a Woody Guthrie student for most of my adult life and the idea just really intrigued me. I thought, wow, that just sounds like something I really would like to do. Didn’t really know how to go about it, but I had a lot of Woody Guthrie materials at that time.

I found a lyric in a compilation of Woody’s work called “Born To Win” by Robert Shelton. The title was “Dance A Little Longer.” I wrote a letter of introduction to Nora Guthrie asking if I could put music to the words, and after doing a little background checking, she gave me the go-ahead. Then later, I was invited to the Woody Guthrie archives which was still in NYC at that time, and I was given four more of Woody’s songs to complete.

I’ve been collecting resources on Woody since I was probably around 20 years old. When I was in my twenties, there wasn’t a lot to find. Most of the stuff, even Bound For Glory was pretty much out of print. You were lucky if you could get a used copy of it. But finding Woody Guthrie records or recordings was very difficult. I found a couple of compilations of Woody and Cisco Houston songs; I got my hands on the children’s songs that he and Marjorie wrote. So that’s the stuff I had in my twenties. And then there was some books, like there’s a book called Hard Hitting Songs for Hard Hit People. Have you ever seen that book?

me: No, I’ve heard of it, but I haven’t seen it yet.

JR: The songs were compiled by Alan Lomax, and then Pete Seeger actually wrote the musical notation for the songs. Then Woody Guthrie wrote the literary introductions for all the songs.

And they’re categorized as farm songs, protest songs, union songs, like that. There’s only about five Woody Guthrie songs in the whole book. But his commentary is on all of the songs, and the songs of Woody’s that were in there, some of them were familiar. “Pretty Boy Floyd” was in there.

Just before the first Woody Guthrie Festival in 1998, I grabbed that book, and I went back through it to find those five Woody Guthrie songs. It was really only about a month before the festival; I knew I had to take a song that no one else would have. I knew “This Land is Your Land” would obviously be taken; “This Train” would definitely be taken, probably all of the standards. I knew some of the songs in this book I had were obscure. So I dug back through it to see what was in there, and I found a song in there that Woody wrote around 1940, about an incident that happened in his hometown of Okemah (pronounced oh-KEE-mah) in 1911, a year before he was born. There was a woman hanged, a woman and her teenage son lynched outside of Okemah named Laura Nelson. It must’ve been such a traumatic event that it was talked about. And Woody heard about it during his childhood.

When he got to New York in 1940, he finally wrote a song about it called “Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son.” It’s in the first person so it’s like Woody was there and heard this woman screaming from the jailhouse. And even when he wrote the notes about it, he described it that way in his notes. You thought he was actually there, but then you check the dates and it’s like a year before he was born that it happened.

So I kind of naïvely took that song to the first Woody Guthrie Folk Festival.

me: Oh, hell yeah.

JR: …to sing in the center of the Red State. I told a couple people about it. I asked Arlo if he’d heard of it – he was there that year – and he said no, he’d never heard of it before. It’d slipped by him. The things you can take for granted, depending on how you’re looking at stuff or where you’re looking at it from.

me: Yeah, exactly.

JR: I told Ray Wiley Hubbard about it, and he said, “Are you actually going to sing that here? Oh my God.” I said, well, yeah, I was planning on it. And he says, “I’ll have the car running out back behind the stage in case you have to leave really quick.”

me: I mean, this is all adding up to be the Woodiest thing you could have ever done.

JR: Yeah, absolutely, but I take no credit. I did it naïvely. I just wanted to have a song that nobody else had.

I knew that Woody wrote on sensitive subjects. It just didn’t occur to me how sensitive that would be in Oklahoma, in the town where it happened. People were pretty taken aback. Some people didn’t know it was a Woody song. “Why would you,” thinking of me as the songwriter, “why would you write a song like that? Why would you sing a song like that?”

Other people were aware of it, so I was asking questions of people that I’d met and kind of made a connection with. “Hey, do you know where this happened? Where did this take place?” And over the next few years, I got a lot of information. At that point, the younger people didn’t really know about it. The older folks knew about it. I got sent to several places in town where it didn’t happen, about as far from where it happened as you could get. I’m not sure if any of that was on purpose or if people just didn’t really know.

So I didn’t find the location until many years later. I kind of gave up on it, and I stopped playing the song. But I was known for playing that song.

That song, along with two of my co-writes, made it into the 100 Songs For 100 Years Songbook that came out for Woody’s Centennial. I’m really proud of that because I have two co-writes in there, and then they put “Don’t Kill My Baby and my Son” in the book, and even put the introduction that I used – you’ve got that record that’s on, Woodeye, right?

me: Yes, I do.

JR: After a time I stopped playing that song, but I was still always kind of interested in that story. My sister-in-law lives in Hawaii, and she is an anthropologist archeologist.

me: Oh man. If I could have done what I wanted with my life, that’s what I would’ve been, probably.

JR: When she lived on the island of Maui, she worked for the state finding historical landmarks to keep developers from wiping them out. She does a lot of research with aerial photography. And she had been in an accident the year before, laid up at home, and we were at the festival, my wife and I, and she was kind of following us vicariously on Facebook. She knew all the stories about this song and that we had looked for the place it happened and failed. She noticed on these aerial photographs, and in a photograph of that lynching… because during that time, in the early 20th century, early 1900s, there was a time period in the South when they took these photographs of lynchings and they’d be made into postcards. You could go into drugstores in the deep South that would be on the postcard rack, pictures of lynchings.

Me: Yeah, I know about that. People’d go down and have a picnic.

JR: And one of the most famous ones was of Laura Nelson and her son hanging from a bridge with a whole bunch of people standing on the bridge looking down at her. And the photo was taken from down the river, looking at the bridge.

***Sensitivity Alert: This is an image of a lynching, published on a postcard****

My sister-in-law knew about all that stuff. And so she texted us: “I think I found maybe where that happened. They said it was a railroad bridge, but in the photograph that’s not a railroad bridge. The bridge that people are standing on is like a cart bridge. It’s not strong enough to hold a train. That’s just like a bridge the horse carts went on before they had cars.” She said that road was probably replaced with a paved road, and that bridge was probably replaced with another bridge where the other road was, or right next to it. And she said, “I was looking at aerial photographs today, and I found two footings next to a bridge.” Actually a bridge where we’d looked at one time, and it even looked like the background in the picture along the river.

Me: Holy cow.

JR: But we never knew if it was really the place. There was no evidence of the old bridge pilings or anything that we could see, but we were looking the wrong direction. We were looking south. And she said, “No, you got to go and look on the north side of the bridge.”

And so we went back out there and looked over the north side of the bridge, and sure enough, there were two really old cement footings on each side. So then we went down underneath the bridge that’s now the road, and there was all kinds of graffiti down there. This is where it happened. And so we knew.

The day I went back, that was a Sunday. And on Sunday when the festival is over, they call it a Hoot for Huntington’s, and it’s unofficial, but whoever’s left in town will play a song at the theater starting at noon. They’ll go for maybe an hour and a half, and everybody will play one more song, and they’ll pass the hat, raising money for Huntington’s Disease.

I just said, man, I’m going to play that song today. I’m going to play, “Don’t Kill my Baby and My Son” today at The Hoot. I mean, it just was so emotional to find that place after so many years of searching.

So I went back, and I was on just before the intermission. I played that song. At the intermission, sometimes I’ll walk down into the audience just to see some friends and say hi. It’s very casual. As I came down the little steps into the theater from the stage, people were going up to use the restroom or get some snacks or whatever. So there’s a lot of empty seats, people milling around.

I saw this Black woman walking towards me, and I realized she was the only Black person in the theater. I just waited for her to get up to me. And when she got up to me, she said, “Thank you for playing that song.”

And I felt funny, her saying thank you for playing a song about a woman that was lynched.

It was kind of strange. And she said, “When I came into the theater, I sat down in the front row, right in the center, in the front row, and three people came in and sat down behind me and said some things that were so hurtful that I can’t even repeat them. And then you sang that song and it made everything all right.”

She gave me a big hug, and then she went back to her seat. When we resumed the show, I peeked through the curtain to see who these three people were that were sitting behind her, and there were three empty seats.

me: Oh, shit. Wow.

JR: And you don’t expect that at the Woody Guthrie Festival; the people that are hardcore right-wing, you don’t expect them to be there. But these three people wandered in and sat right behind this woman, and then said some ugly things to her. I still don’t know what, but I’m sure it was awful. And so I wrote another song that’s on my album, Baladista, about that incident called “Sticks and Stones.”

And the woman, she still comes to the festival every year. She’s a volunteer at the festival every year, and we’ve become really good friends now for years.

me: That’s amazing. But this also helps me understand something. I remember what Tim Z. Hernandez said: “Joel Rafael was the only person who reached out and said, what can I do to help?”

And I have a better feel for why he would say that: that you would get ahold of what he’s doing because you also seek out the location. You were recently with him at readings for his latest book, They Call You Back. How did that go? Did did he have a decent audience show up?

JR: Really fun. Yeah, big turnout at both of them. His readings were really well attended. His publisher’s behind him pretty strong, which is nice. And it’s such a powerful story; it kind of picks up where All They Will Call You left off. Then what happens is a voice inside keeps calling him to look at his own life.

me: And that’s what I mean: He explains how something innate was encouraged in his childhood; different things that happened in his family helped reinforce that natural calling to be able to hear. I would say – this is me interpreting, not his words – that he can hear the voices of the lost, wanting to be found.

JR: Yeah. He talks about ghosts a lot.

Me: Yeah. And I intuit a little bit of that in your story about looking for the bridge.

JR: Well, Tim references that in his most recent book. In one of the chapters, he goes to the bridge, he’s with me and my wife and another guy. I took him there, I guess it might’ve been the next year after I’d found it. I took Will Kaufman and his wife and Tim Hernandez out there because they wanted to know what it was. I was pretty secretive about it at that point. I didn’t want everybody just going out there.

***Sensitivity Alert: This is quilted fiber art titled Laura got Lynched from the Bridge****

What happened is when he put that event together to dedicate a headstone at the mass grave in Fresno, a lot of people got invites. Somehow, he must have hooked up with a mailing list from Woody Guthrie Publications or something. So a lot of people that have been kind of involved with Woody over the years got a notification about it happening. And when I got my invite, in an egotistical way, I thought to myself, “oh, well, maybe I’m getting this invite because maybe he needs somebody to come up and sing ‘Deportees’ for the event.” I mean, that was pretty unrealistic of me to think that looking back…

me: Yes and no, because that’s a natural assumption; it makes sense that the song needed to be there.

JR: And I didn’t know how many people had heard about it. And so I contacted Tim, and what I didn’t know is a whole lot of other songwriters had been contacting him as well, but they all wanted the names (of the Mexican nationals.) And in a way, to Tim, his perception was it just felt very selfish. All they wanted was the information so that they could be the ones to spread the word about it.

And when I called him thinking that maybe he needed me to come up there and sing that song, I didn’t say, “Do you want me to come sing this song?” I wasn’t presumptuous in that way, and I didn’t ask him for the names, even though I was just as curious. For me as a person, the way I approached it was to say, well, “Is there anything I can do to help you?”

Me: That’s what I got from reading the book: that he was impressed by your manner.

JR: Quite frankly, his answer to me was, “No, not really. We’ve got it covered.” And I thought, well, okay. And then we had to decide if we were even going to go or not, and then we decided, well, we had to go. We couldn’t not go, just because of my history with that song and with Woody and all that. So we went, and that’s when I met Juan Martinez, who was the one who inspired my song “El Bracero.”

There was a dinner the night before at a Mexican restaurant owned by Jaime Ramirez whose uncle and grandfather had been victims of the plane wreck at Los Gatos. I commented on how ironic it was that a song by Woody written decades earlier would ultimately help find the names of the victims.

…he (Juan Martinez) told me about an event he was coordinating,” Rafael continued, “it was like two weeks later, to dedicate a portion of California US 101 as the Bracero Memorial Highway, because the victims of the plane crash in Woody’s song were not undocumented workers, like everybody thought… being known by the name ‘deportee.’ They were actually in the States legally working under contract under the Bracero program, which is a program that was instituted around the beginning of World War II to supplement the labor force in the agricultural areas of our country.” – Zebra.org

Then Juan asked me if I’d heard about the make-shift transport vehicle that exploded and killed 14 Braceros. And did I know about the 32 Braceros that were killed when their bus was stuck on the railroad tracks in Chualar, CA. and was hit by a train?

When I said no, he said, “That’s because no one wrote a song about those ones.”

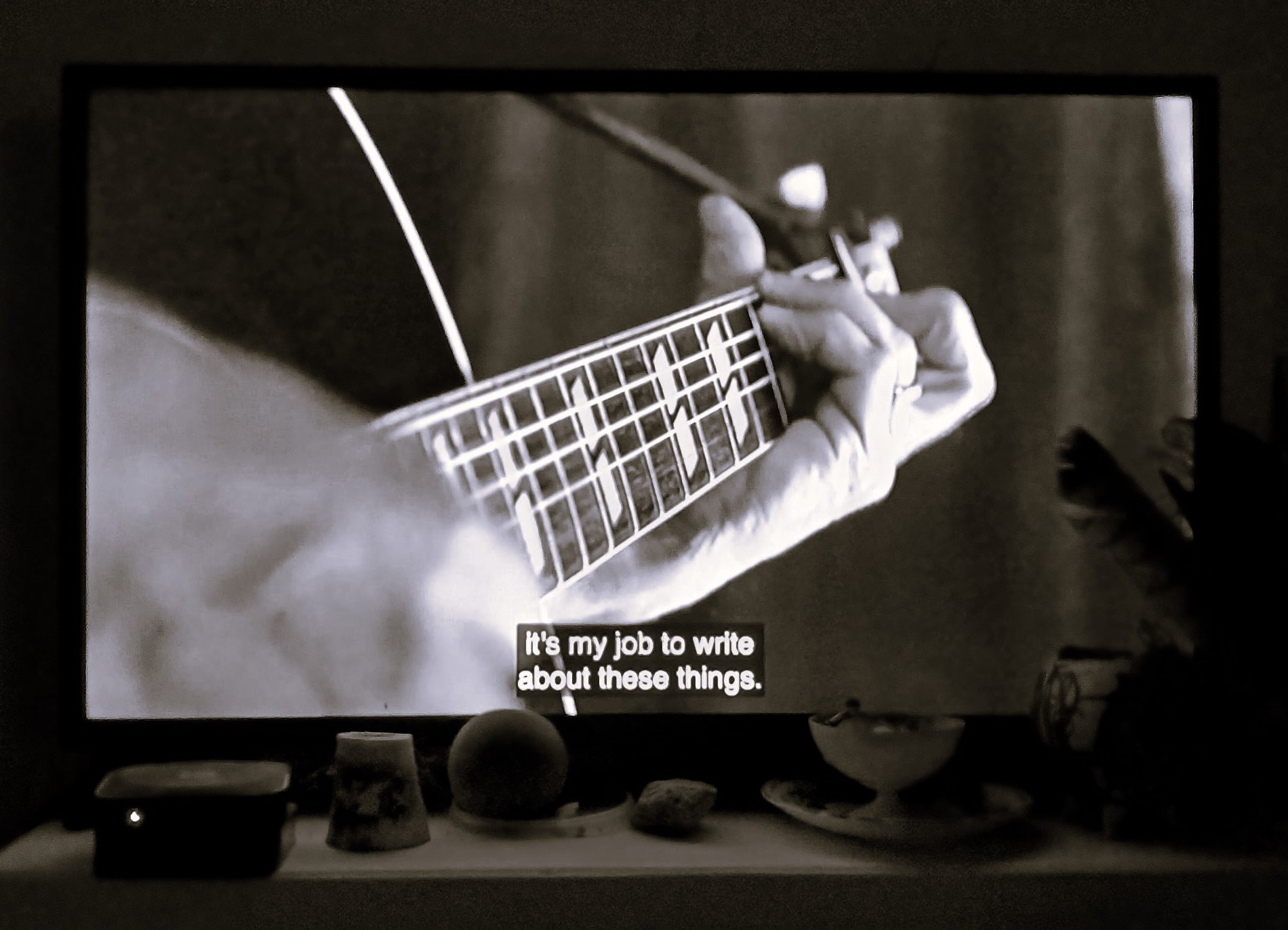

The two of us ended up in a movie called A Song for Cesar.

It’s a documentary about the music that drove the movement to create the United Farm Workers Union. I wasn’t part of that. Those were people like Joan Baez, Crosby and Nash, Carlos Santana, and a lot of Chicano artists that were the musical element of that movement. And so these two guys that made the movie, Andres Allegro and Abel Sanchez, contacted my manager’s office. I was managed by the same management as Graham Nash at that time. And because Graham and David had done a song called “Field Worker,” that they wanted to use in the movie.

“It’s my job to write about these things.” – Joel Rafael, A Song for Cesar

My manager told them about my song “El Bracero,” which I’d written after going to the Tim Hernandez event, and they ended up using it. They used the instrumental part under Dolores Huerta’s interview, and that was a great honor. Then they ended up having me come up and lip-sync the song as if I was recording it at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, and then had these two girls that it turns out are from the group Los Cenzontles (The Mockingbirds) which is the group that’s in the other movie that I have a song in, Linda and the Mockingbirds.

I never made the connection until about a year after both movies have come out. I go, wait a minute, those are the same kids that are in the other movie.

me: Kind of cool.

JR: So I just offered to help. That was my way of saying, well, if he’s going to ask me, I’m not going to offer to come up and sing a song, but I’ll ask him if there’s anything I can do, and if that’s what he’s got in mind, he’ll say something. And he just said, no, we’ve got it totally covered. And he didn’t know who I was. I just happened to be on a list that got the invite. But Tim and I have consequently become really close friends, and he’s pulled me in for his book readings and presentations that are nearby or that make sense for us to do together.

me: I personally really, really appreciate the combining of literature and music.

JR: My whole thing is that creativity is creativity.

me: Me too. My statement is: All these things are all the same. They’re different vocabularies. Sometimes you gotta use paint. Do you paint also?

JR: Yeah, I dabble with it. I’m not a painter, but I do dabble with it. I’ve taken watercolor classes before.

me: Watercolor’s so hard. I can’t.

JR: Yeah, it’s so different than acrylic or oil. You got to use the paper. Watercolor’s all about the light, letting the light shine through you and using the water to make the paint grow at. But my art instructor said…

(Joel gets up to show me a photo on the wall.)

Doug Durrant painting, watercolor art by Joel Rafael

Here he is. Can you see him? He’s no longer with us and his name is Doug Durrant. He was my drawing instructor at the community college. And we became really good friends. One of the things he pointed out is that literally everything you look at in our lives is a representation of art. The faucet in your bathroom, somebody designed that. Somebody drew that and made up what the shape was going to be and how that was going to look. Your furniture, just everything around you was designed by an artist.

And so art is so critical to our world, but here in the United States, it’s the always first thing they cut when they’ve got to cut the budget; it’s the first thing they eliminate, but it’s so essential to everything. It’s all around us, 24-7: a light switch, a handle on a door. They were all created by a designer. People take stuff for granted in the political times we’re living in right now; the things that we take for granted are the things they’re going to take away.

me: And that’s what folk is, in my opinion. Folk is preservation; it’s why those things we take for granted will be able to survive our current political environment – because those things reside within people.

I say all the time that we hold our emotions in items. And so when I’m writing a song, I’m adding things like this teacup that belonged to my grandmother, this rock I found, because those are where my emotions are hiding. So in the song format, if I’ve done my job correctly, the person listening will know: Maybe she doesn’t have the teacup from her grandmother, but she might have something else that means the same to her. You understand the job that tangible item is doing.

JR: Right. The energy of ancestors.

me: That continuum is the one thing I feel is so lost in mainstream American culture – not our real American culture, which is more of a patchwork blanket made up of real stories – but the American culture that thinks art and music are dispensable. But folk music, folk culture is how we will survive as soon as it’s safe to breathe.

JR: Well, it’s like my friend John Trudell said, the big lie is that civilization is civilized because it’s not. It’s the opposite. The history of this country has been a violent one, and it becomes so evident when we’re going through the kind of stuff we’re going through now.

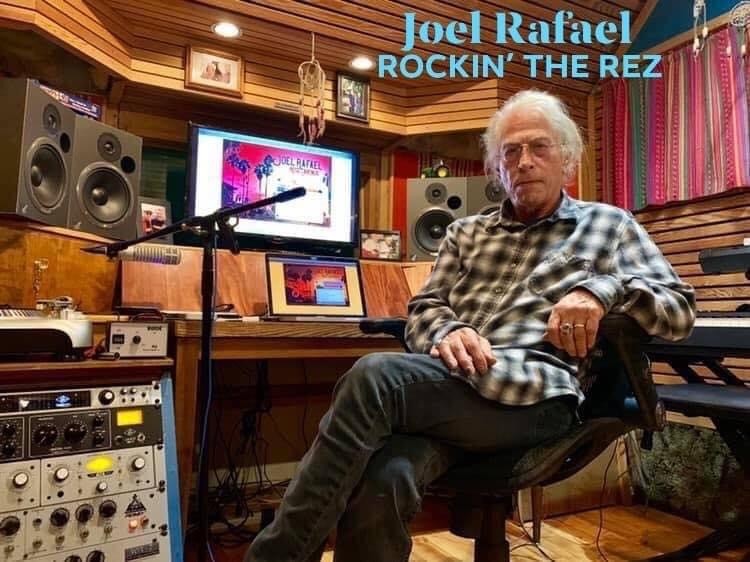

me: I want to talk about Rockin’ the Rez. Speaking of preservation of culture, you’ve been doing that for a long time.

me: I want to talk about Rockin’ the Rez. Speaking of preservation of culture, you’ve been doing that for a long time.

JR: Yeah. Going on 14 years.

me: So how did you decide that was the thing you were going to do? How did that come about?

JR: Well, I don’t really consider myself like a DJ.

me: No, but you’re the guy that sits in the chair. You choose the music, correct?

JR: Full disclosure: my wife Lauren curates the playlist and I assemble and host the show, so we do it together. I never set out to be a DJ, but I’ll say as a younger person one of the things I explored was going into radio because I’ve got the voice for it, but historically it’s been very difficult to get into. Very locked in community.

As musicians and performing artists, we try like hell to get our stuff on the radio. At one time, if you could get your stuff on the air, that meant you could make a living. It doesn’t mean that anymore, but it did at one time, so as a younger performer, I was always trying to get stuff on the radio, and even trying to get on the radio as a host, but I never could. So I just kept pursuing things as I did and I became a performing artist and went down the roads I went down, and kind of carved a niche for myself. At some point, as radio opened up a little bit, some of my songs got airplay. In the 90s, when the AAA format and the Americana format came about, my songs started to get played. And it was amazing for that to happen. And at some point along the way, Sirius was playing some of my stuff.

I was asked at a certain point to do a guest DJ spot for Sirius. I just brought in a bunch of my favorite songs. Mary Sue Twohy was the one who arranged it; she set me up in the studio and introduced me, and then I just kind of took the hour. They do that with artists from time to time. And so I had this guest show, but I wasn’t really pursuing radio in any way. And this was about 14 years ago.

About 15 years ago, there were some very bad fires, a bunch of ’em in my area, and a lot of people were evacuated. There’s a lot of Indian reservations in San Diego County, and there’s one that’s right near us called the Pala Indian Reservation. After the fires back then, they decided to establish a community radio station so that they would have an emergency information system on the Rez that people could tune into. They just thought it would be a good communication tool to have. So they started a community radio station. And at a certain point, the local paper ran an article about the station and about the program director, and one of the things they said was that they were looking to have a few more local programs.

I was just sitting there talking it over with my wife and thinking of all these years that I’ve tried to get my stuff on the radio. The way things are in radio now, everything streams worldwide. So if he wanted to have me do a program of some kind, that would be an hour of FaceTime streaming internationally every week. It wouldn’t be all my music, but I could play a song or two of mine and then play other songs from our collection. I have a lot of friends in music, and when you get to be my age and you live through the musical era I lived through, you’ve got some resources in that respect. So we talked it over and we thought, well, it’s on the Pala Indian Reservation. John Trudell is a close friend. Maybe we could use his song, “Rockin’ The Res” as the theme song.

me: Oh, yeah, okay!

JR: He was cool with it, so I went down there and saw the program director. I took him the Sirius show that I’d done, and told him I had this idea for a show.

He said, “Well, why don’t you make me three shows so if I like it, we can put it on and I’ll have a couple back-up shows so it’s not a scramble.”

So I came home and I made three shows. He said, “Okay, I’m going to give you Saturday morning at 10 and a repeat on Sunday night at eight.” So that’s been my time slot. But one of the problems is most of his shows are done in their studio, and I didn’t want to drive down there every week and do a show down there. I’ve got a studio here, so I do it here.

We’re now a Pacifica syndicated show, so I have no idea how many people hear the show, but it’s all over the country and all over the world. We have fans in Europe, in places I’ve played, and it’s given me more visibility, given me that airtime.

The show always starts with our theme song, Trudell’s “Rockin’ the Res.” There’s always at least one more John song, and usually a couple, because our show really is kind of dedicated to him. We like to keep the show as content-focused as we can with support for the common people.

me: I have a quote that I pulled out of somebody else’s interview with you: “I’ve been drawn to speak out for the disenfranchised.” You do it from a place of sincerity, because those voices are speaking to you and want to be heard.

JR: And because sometimes we’re honestly outraged about stuff, and I just have to talk about it. Graham Nash said to me once, “Yeah, you’re an activist.” I mean, I never really thought of myself particularly that way, but it turns out that’s what I do.

me: It is what you do.

JR: But as Graham said to me, “There’s a price to pay for that.”

me: People here in the States seem to think of art as entertainment, as an escape. It’s a commodity. It’s something you buy like a sandwich –

JR: Go out and have a drink and and forget about the issues of the day, whereas in Europe and other parts of the world, Art is all about the issues. So it’s right in your face and you have to have an opinion. There’s a certain element of society that doesn’t want to hear what I might singing about. They just want to be entertained, and sometimes I just don’t fit that bill.

me: Same here.

One of the radio stations promotes Rockin’ the Rez as ‘hosted by Joel Rafael, Keeper of the Flame for John Trudell and Woody Guthrie.’ That’s a tangible example of people really understanding the value of Folk culture preservation. Joel doesn’t advertise himself like that, but he puts in the footwork.

Joel Rafael is an artist, making pictures with words: you can “see the man bending down with the short-handled hoe.” In this song, “El Bracero,” he counts the voiceless, the nameless, through bridge of a song that could be the story of any one of them:

28 to the Canyon de Los Gatos

14 when the truck van exploded

32 when the train hit that bus

We died without our names

Do they seek him out? Maybe. Maybe people will hear their stories now.

debora Ewing writes, paints, and screams at the stars because the world is still screwed up. She improves what she can with music collaboration, peer-review at Consilience Poetry Journal, or designing books for Igneus Press. Follow @DebsValidation on X and Instagram. Read her self-distractions at FolkWorks.org and JerryJazzMusician.com.

Joel Rafael – Bringing Woody to the World and Back

in which we discuss Italian art, Spain, Okemah OK, co-writing with Woody Guthrie, defending the nameless, and how doing things leads to other things