CHRIS KING AND THE MUSIC OF EPIRUS

Part 2 of 2: An Interview with Christopher C. King

CLICK FOR PART 1: A PROFILE WITH CHRISTOPHER C. KING

“Every time the needle hits the grooves, a miracle is performed.” – Chris King

“Every time the needle hits the grooves, a miracle is performed.” – Chris King

I had the opportunity to chat with Chris this past August, a week before he left on another extended trip to Epirus:

I had the opportunity to chat with Chris this past August, a week before he left on another extended trip to Epirus:

PS: You are well known as an archivist, collector of 78 records and as a curator & producer of a growing number of CD and vinyl compilations from your extensive collection. Can you share how you came to 78 collecting?

CK: I began collecting 78s at the age of 15 when I discovered a small stack of pre-war discs; many black gospel but also some blues, hillbillly, Cajun, within an old shack on my grandparent’s farm. My dad also collected music–including 78s but his taste was quite different from mine. And we were both natural-born collectors, so I just inherited the gene but modified the organism.

PS: I first became aware of you a half decade ago via the JSP box set of Epirotika and have become something of a rabid consumer of everything that has followed. How did you first come across the music of Epirus and what was it that drew you in so completely?

CK: I first discovered the music of Epirus and southern Albania when I bought a dozen or so beat-to-hell 78s in Istanbul around eight years ago. Among those discs was one by the clarinet player, Kitsos Harisiadis. When I sat and listened deeply to the music I became very aware that there was some intentionality inherent in the music–something behind or underneath that made the music purposeful beyond simply listening or dancing. It was this unknown purpose that drew me in, that I wanted to investigate.

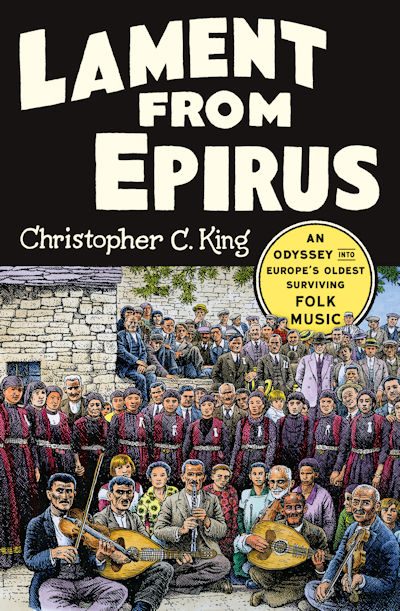

PS: Your Kitsos Harisiadis: Lament in a Deep Style 1929-1931 compilation was just released this summer on Jack White’s Third Man Records. It has been in nonstop rotation at our house for the past few months and from the opening Skaros to the closing Mirologi, this is a really beautiful record. In your new book Lament for Epirus, you discuss the importance of the relationship between the musicians and the traditional, rural cultures that nurtured them, citing seminal North Carolina musician Tommy Jarrell and the generations of musicians that he has inspired as a case study. Can you share what you mean by “What is etched in these curious black discs no longer exists in the world.”?

CK: What I mean is that in the rural American south, the traditional context of necessity between music and lifestyle…of music and culture, has largely disappeared. The context within which Tommy Jarrell played in rural Toast, North Carolina made his music necessary and it also insured a degree of continuity and a passing-down of traditional sounds and functions within the music. But those generations of musicians that learned Tommy’s style lacked the tightly knit cohesive social structure in which Tommy’s music existed. When these younger musicians moved away, they could not create this context because context is organic, not synthetic. They might be playing the right notes, the right bow style, the right ornaments, but the music is no longer being played for a particular group of people for the particular reasons in which is originally existed. It used to be vital music. Now it is optional music. And when I say that the music etched in these curious black discs no longer exists in the world, I mean that when it was captured…Delta blues, Appalachian banjo tunes, Polish fiddle tunes, the music had a necessary context that made it relevant, vital, and necessary. This context no longer exists and without the context the music also dies.

PS: In Lament for Epirus, you dedicate a chapter each to clarinetist Kitsos Harisiadis as well as violinist Alexis Zoumbas. It’s certainly not difficult to hear the effervescence in Harisiadis’ playing, even in his laments. In contrast, Zoumbas’, who emigrated to America, playing is dark and brooding.

PS: In Lament for Epirus, you dedicate a chapter each to clarinetist Kitsos Harisiadis as well as violinist Alexis Zoumbas. It’s certainly not difficult to hear the effervescence in Harisiadis’ playing, even in his laments. In contrast, Zoumbas’, who emigrated to America, playing is dark and brooding.

CK: Yes, I intentionally juxtaposed these two chapters, side-by-side, of Zoumbas and Harisiadis to illustrate this notion of musical inspiration. Zoumbas’ music hurts. It is sourced from xenitia, a longing for one’s homesoil and a privation of place. Harisiadis’ music is sourced from a place of belonging, of peace and place. Zoumbas’ music is dark. Harisiadis’ music is light. Musical inspiration can come from pain or it can come from happiness. I think it is essential to know that you can trace this, detect this, in music particularly from the music of this region. Zoumbas and Harisiadis would have been contemporaries and they would have shared nearly identical experiences when growing up and learning the music. Where everything diverged…separated between light and dark, is when Zoumbas moved to the US and Kitsos stayed in Epirus.

PS: You write about hearing Zoumbas’ Epriotiko Mirologi for the first time describing “As the needle tracked out into the dead grooves, I felt as if I had been taken apart and rearranged.” I had a very similar experience, playing that title track of Alexis Zoumbas – Lament for Epirus 1926-1928; inexplicably tearing up as I played that title track over and over for the better part of an hour and countless times since. How do we explain the impact of this on the human psyche and why this affects us in such a way?

CK: This is a very good, very interesting question because I have no real explanation. I hear this same or this similar response from a very broad section of friends, colleagues, villagers, urbanites…Christ, just about everyone has this reaction and yet we all struggle with an explanation. There are though, at least, a few valid responses. Several people have suggested that the pentatonic structure of the mirologi which contains both the major pentatonic and the minor pentatonic in the say key note is a primal musical motif. That it taps into something arcane and primeval in our souls. And the specific structure of the mirologi with its embellishments and repeated motifs was designed to illicit a response from our psyche. Because it is ancient, I think there is some truth to this. Other people have suggested that one needs to be psychologically inclined or trained to have this reaction. We need to be able to experience vulnerability with the music we hear. I think there is some truth in this as well.

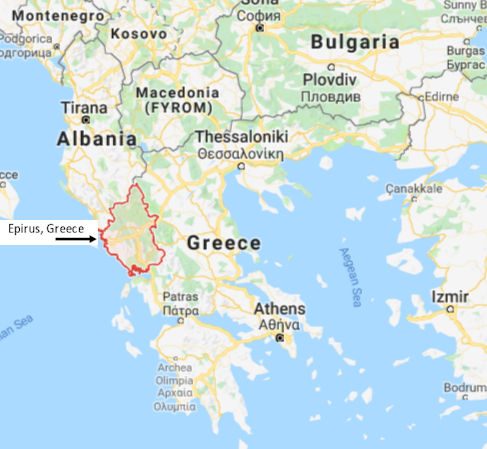

PS: I gather that you have spent quite a bit of time doing field work in Epirus?

CK: Yes, I have visited often over the last seven years, and practically every visit has involved some aspect of field recording and field work. So far I’ve issued three CDs of field recordings.

CK: Yes, I have visited often over the last seven years, and practically every visit has involved some aspect of field recording and field work. So far I’ve issued three CDs of field recordings.

PS: What keeps you coming back?

CK: I keep on returning because rural Greece is a vast unexplored musical territory. It almost seems boundless. Because Greek music theory and culture at one time predominated the southern Balkans. There are so many musicians that I haven’t heard and so many small pockets of musical eccentricity that I have yet to explore. I’m afraid I’ll never exhaust the musical riches of the region.

PS: In your book you recall explaining to a villager that you are in Epirus because you love their music and he replies: “Are you sure? Most people don’t like this music. Especially Greeks. Have some more tsipoura (moonshine).” Why is that, do you suppose?

CK: It is because of globalization, cultural homogenization, a general trend of humanity to move towards bland uniformity. This is more acutely felt in the US and in parts of Europe where most ethnic or rural music has disappeared. But in Greece, there are significant numbers of people that strive to become more European. Therefore, tastes need to be modified. Change is expected. So, some Greeks simply dislike traditional music. More importantly, throughout Greece there is a diversified sound of traditional musics found in villages and in sub-regions. A person from Crete may love Cretan music to the expense of all other Greek music, including that of Epirus. Same thing goes with many of the different chains of islands in the Aegean, regions of Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly, Peloponnese. These regions have their own musical identity and it kinda dictates that you identify with your musical region. And Epirus is a small, sparsely populated region. Therefore, many Greeks just simply can’t “get into” the tonalities of the music found in Epirus–particularly if you are not from there.

PS: You’ve had a number of “celebrity” endorsements including two of my favorite filmmakers Jim Jarmusch and Terry Zwigoff as well as artist Robert Crumb who has also contributed covers to a number of your recordings as well as your new book. How did you two meet?

CK: I met Robert…jeez…like around 10 years ago when he came to Richmond, Virginia, a city near me, to give a dog and pony show for his book Genesis. We met after the event and really hit it off both in terms of friendship but also in terms of swapping records, ideas, writings.

PS: Your production company, Long Gone Sound, has worked with a number of different record companies and most recently with Jack White’s Third Man Records. Can you share how that relationship came about?

CK: I formed a relationship with Third Man Records through two people; my friend and graphic designer Susan Archie and my friend and fellow producer/boss Dean Blackwood of Revenant Records. Both of them encouraged me to approach Third Man with my peculiar projects and they in turn got the ear of Ben Blackwell and others at Third Man. It has been a sublime symbiotic relationship with Third Man.

PS: I stumbled upon a photo of you playing laouto. You play this and other music?

CK: Well, I play Epirote-style laouto and Epirote-style violin. My first instrument was the banjo. I inherited my grandfather’s banjo from the 1930s. Then I started playing finger-picking style guitar, basically country ragtime guitar. I can play some old-time fiddle tunes and one of my early loves was Cajun fiddle. I can get around on a Cajun diatonic accordion and the same with a mandolin but I’m not terribly good at any instrument. I mainly learn them so that I can learn the particular language of the music; the scales, the techniques and ornaments that are unique to a particular form of folk music.

PS: What’s next for you, Chris?

CK: I’m writing two books; one non-fiction and one novel. The non-fiction is called Dead Wax: Murder, Music and Memory. It’s about murder ballads and collective memory. The novel is called An Offering. It’s about a murder that takes place in 1929 in southwest Virginia. It is a story about a man, a deer and a train. I’m also producing and remastering a collection of violin music from India from 78 rpm discs, both Hindustani and Carnatic. Finally, I’m establishing an Archive of Epirotika Music in the village of Kato Pedina in Zagori, Epirus. So, I have quite a few things on the horizon.

Chris King’s book Lament for Epirus: An Odyssey into Europe’s Oldest Surviving Folk Music as well as his CD releases of Epirotika can be found on amazon.com

Additional related great CDs:

Five Days Married & Other Laments: Song & Dance from Northern Greece 1928-1958

Beyond Rembetika: The Music and Dance of the Region of Epirus 1919-1958

Vitsa: Takimi of Epirus (Field Recordings from Zagori, Epirus 2014)

Parkalamos: Yiannis Chaldoupis & Moukliomos (Field Recordings from Pogoni, Epirus 2014)

Demotika: Authentic Village Music From Greece 1917-1955

CLICK FOR PART 1: A PROFILE WITH CHRISTOPHER C. KING

Pat Mac Swyney is a Los Angeles based musician and teacher who plays Trad. Jazz with The Swing Riots Quirktette; Balkan with Nevenka; and Old-Time with The Shakytown Ramblers, Dead Rooster & Sausage Grinder.

CHRIS KING AND THE MUSIC OF EPIRUS

Part 2 of 2: An Interview with Christopher C. King