Valentines Beware!

The Tale of The Lyttle Musgrave

VOICE NOTES: A FOLK DIVA’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY Number 56

February 1, 2024

Number 56, February 1, 2024

Valentines Beware! The Tale of Lyttle Musgrave

February is considered by some as the month of love because of Valentine’s Day on February 14. As you have probably noticed, the stores are already chock full of Valentine’s Day stuff ~ cards, candy, flowers. But as the ancients always remembered and talked about, there is, can be, a lurking danger in love, even dangers that can lead to tragedy.

I don’t mean to throw a wet blanket on the celebrations of love that we participate in, get to appreciate and enjoy. But as a scholar of Jean Ritchie’s ballads I see another level.

In the tale of “Lyttle Musgrave” the way love can lead us astray is borne out in an astonishing and ancient fable.

Background

In Vol. 2 of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads” by Francis James Child, entry #81 appears as “Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard.” The description identifies this “ancient” ballad as deriving from the mid-17th century, and is described as “popular” because it was quoted in many “old plays.” Child then goes on to describe the versions he uncovered and all of the variants. These variants revolve around small details, while the story itself remains unchanged. In reading this material, I often wonder, in fact I know, that these were handed down partly as morality tales or warnings to future generations of what could happen in romantic situations, in this case, among landed gentry/royal figures showing us the way of harm. In fact, the last stanza of “broadside C” states:

This sad mischance by lust was wrought;

Then let us call for grace,

That we may shun this wicked vice,

And mend our lives apace.”

Given the length of the centuries of time that separated these earliest records of “Little Musgrave” and the version that traveled and survived all the way to the Appalachian hills of Kentucky in the early twentieth century as “The Lyttle Musgrave,” it’s absolutely miraculous that we have this ballad, today printed in Jean Ritchie’s “Singing Family of the Cumberlands” and her “Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians.” This song was taught to Jean by her Uncle Jason Ritchie, a collector and curator of a wealth of ballads and other songs during his lifetime. Jean notes in the second volume referred to above that the spelling of “Lyttle” comes from Uncle Jason himself and was perhaps influenced by the presence of an old English dialect within the language of the lyrics. It’s still pronounced as “little.”

On the day that Uncle Jason taught “Lyttle Musgrave” to Jean, he has a dialogue with her that is recounted in her Singing Family of the Cumberlands:

‘Now what song of all the ones I sung you today did you like the best? That one about the Lyttle Musgrave? It is a pretty thing, the language of it, and the dainty music. Reason I asked you is I aim to sing your best liking to you for a parting.’ Whereupon he stood up very straight, put one hand on my shoulder, and looked away off somewhere into the pale fall sunset and sang that lovely lonesome song. The little branch waters sang along in a sweet dulcimer drone, like its music was made just in tune for the ballad. Uncle Jason’s tall, black-clad frame swayed to the quavery ups and downs of the song and his eyes clouded over with memories. He sang the whole song, all twenty-seven verses of it, and I don’t have to tell you that I was black dark getting home.

Story synopsis (link below for complete Wikipedia article):

Little Musgrave (or Matty Groves, Little Matthew Grew and other variations) goes to church on a holy day either “the holy word to hear” or “to see fair ladies there”. He sees Lord Barnard’s wife, the fairest lady there, and realises that she is attracted to him. She invites him to spend the night with her, and he agrees when she tells him her husband is away from home. Her page overhears the conversation and goes to find Lord Barnard (Arlen, Daniel, Arnold, Donald, Darnell, Darlington) and tells him that Musgrave is in bed with his wife. Lord Barnard promises the page a large reward if he is telling the truth and to hang him if he is lying. Lord Barnard and his men ride to his home, where he surprises the lovers in bed. Lord Barnard tells Musgrave to dress because he doesn’t want to be accused of killing a naked man. Musgrave says he dare not because he has no weapon, and Lord Barnard gives him the better of two swords. In the subsequent duel Little Musgrave wounds Lord Barnard, who then kills him. (However, in one version “Magrove” instead runs away, naked but alive.)

Lord Barnard then asks his wife whether she still prefers Little Musgrave to him and when she says she would prefer a kiss from the dead man’s lips to her husband and all his kin, he kills her. He then says he regrets what he has done and orders the lovers to be buried in a single grave, with the lady at the top because “she came of the better kin”. In some versions Barnard is hanged, or kills himself, or finds his own infant son dead in his wife’s body.

See Wikipedia article here.

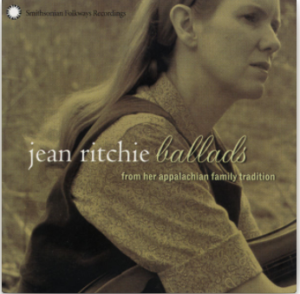

Here is Jean’s recording from her album “Ballads” on Smithsonian Folkways. Lyrics are below as found in her Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians.

Here is Jean’s recording from her album “Ballads” on Smithsonian Folkways. Lyrics are below as found in her Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians.

Lyttle Musgrave

One day, one day, one fine holiday,

As many there be in a year,

We all went down to the old church house,

Some glorious words to hear.

Little Musgrave stood by the old church door,

The priest was at a private mass,

But he had more mind of the fair women

Than he had for Our Lady’s grace.

The first come in was a-clad in green,

The next was a-clad in pall,

And then come in Lord Arnol’s wife,

She’s the fairest one of them all.

She cast her eye on Little Musgrave,

As bright as the summer sun,

And then bethought this little Musgrave,

This lady’s heart have I won.

Quoth she, I have loved thee, Little Musgrave,

Full long and many a day.

Quote he, I have loved you, fair lady,

Yet never one word durst I say.

I have a bower at the Bucklesfordberry,

It’s dainty and it’s nice,

If you’ll go in a-thither, my little Musgrave,

You can sleep in my arms all night.

I cannot go in a-thither, said little Musgrave,

I cannot for my life,

For I know by the rings on your little fingers,

You are Lord Arnol’s wife.

But if I am Lord Arnol’s wife,

Lord Arnol he is not home,

he is gone unto the academie

Some language for to learn.

Quoth he, I thank you, fair lady,

For this kindness you show to me,

And whether it be to my weal or my woe

This night I will lodge with thee.

All this was heard by a little footpage,

By his lady’s coach as he ran,

Says he, I am my lady’s footpage,

I will be Lord Arnol’s man.

Then he cast off his hose and shoes,

Set down his feet and he run,

And where the bridges were broken down,

He smote his breast and he swum.

Awake, awake now, Lord Arnol,

As thou art a man of life,

Little Musgrave is at the Bucklesfordberry

Along with thy wedded wife.

If this be true, my little footpage,

This thing thou tellest to me,

Then all the land in the Bucklesfordberry

I freely will give it to thee.

But if it be a lie, thou little footpage,

This thing thou tellest to me,

On the highest tree in the Bucklesfordberry

It’s a-hanged thou shalt be.

He called up his merry men all,

Come saddle to me my steed,

This night I am away to the Bucklesfordberry

For I never had greater need.

Some men they whistled and some they sung,

And some of them did say,

Whenever Lord Arnol’s horn doth blow,

Away, Musgrave, away.

I think I hear the noisey cock,

I think I hear the jay,

I think I hear Lord Arnol’s horn:

Away, Musgrave, away.

Lie still, lie still, my little Musgrave,

Lie still with me til morn,

Tis but my father’s shepherd boy

A-callin’ his sheep with his horn.

He hugged her up all in his arms

And soon they fell asleep,

And when they awoke at ear-lie down

Lord Arnol stood at the bedfeet.

Oh how do you like my coverlid,

Oh how do you like my sheet?

Oh how do you like my fair lady

Who lies in your arms so sweet.

Oh I like your handsome coverlid,

Likewise your silken sheet,

But best of all your fair lady

Who lies in my arms so sweet.

Arise, arise now, Little Musgrave,

And dress soon as you can;

It shall not be said in my countree

I killed a naked man.

I cannot arise, said Little Musgrave,

I cannot for my life,

For you have got two broadswords by your side

And I have got nary a knife.

I have two swords down by my side,

They both ring sweet and clear,

You take the best, I’ll keep the worst,

Let’s end this matter here.

The first stroke that Little Musgrave struck,

He wounded Lord Arnol full sore;

The first stroke that Lord Arnol struck

Musgrave lay dead in his gore.

Then up and spoke this fair lady,

In bed where as she lay,

Although you are dead, my little Musgrave,

Yet for your sake will I pray.

Lord Arnol stepped up to the bedside

Whereon these lovers had lain,

He took his sword in his right hand

And split her head in twain.

Happy Valentine’s Day everyone! And as always, thanks for reading!

Love and Blessings,

Photo by Cam Sanders

Susie

________________________________________________

Award-winning recording artist, Broadway singer, journalist, educator and critically-acclaimed powerhouse vocalist, Susie Glaze has been called “one of the most beautiful voices in bluegrass and folk music today” by Roz Larman of KPFK’s Folk Scene. LA Weekly voted her ensemble Best New Folk in their Best of LA Weekly for 2019, calling Susie “an incomparable vocalist.” “A flat out superb vocalist… Glaze delivers warm, amber-toned vocals that explore the psychic depth of a lyric with deft acuity and technical perfection.” As an educator, Susie has lectured at USC Thornton School of Music and Cal State Northridge on “Balladry to Bluegrass,” illuminating the historical path of ancient folk forms in the United Kingdom to the United States via immigration into the mountains of Appalachia. Susie has taught workshops since 2018 at California music camps RiverTunes and Vocáli Voice Camp. She is a current specialist in performance and historian on the work of American folk music icon, Jean Ritchie. Susie now offers private voice coaching online via the Zoom platform. www.susieglaze.com

Valentines Beware!

The Tale of The Lyttle Musgrave

VOICE NOTES: A FOLK DIVA’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY Number 56

February 1, 2024