This Machine… Does Things

Number 5 - January 2026

This Machine

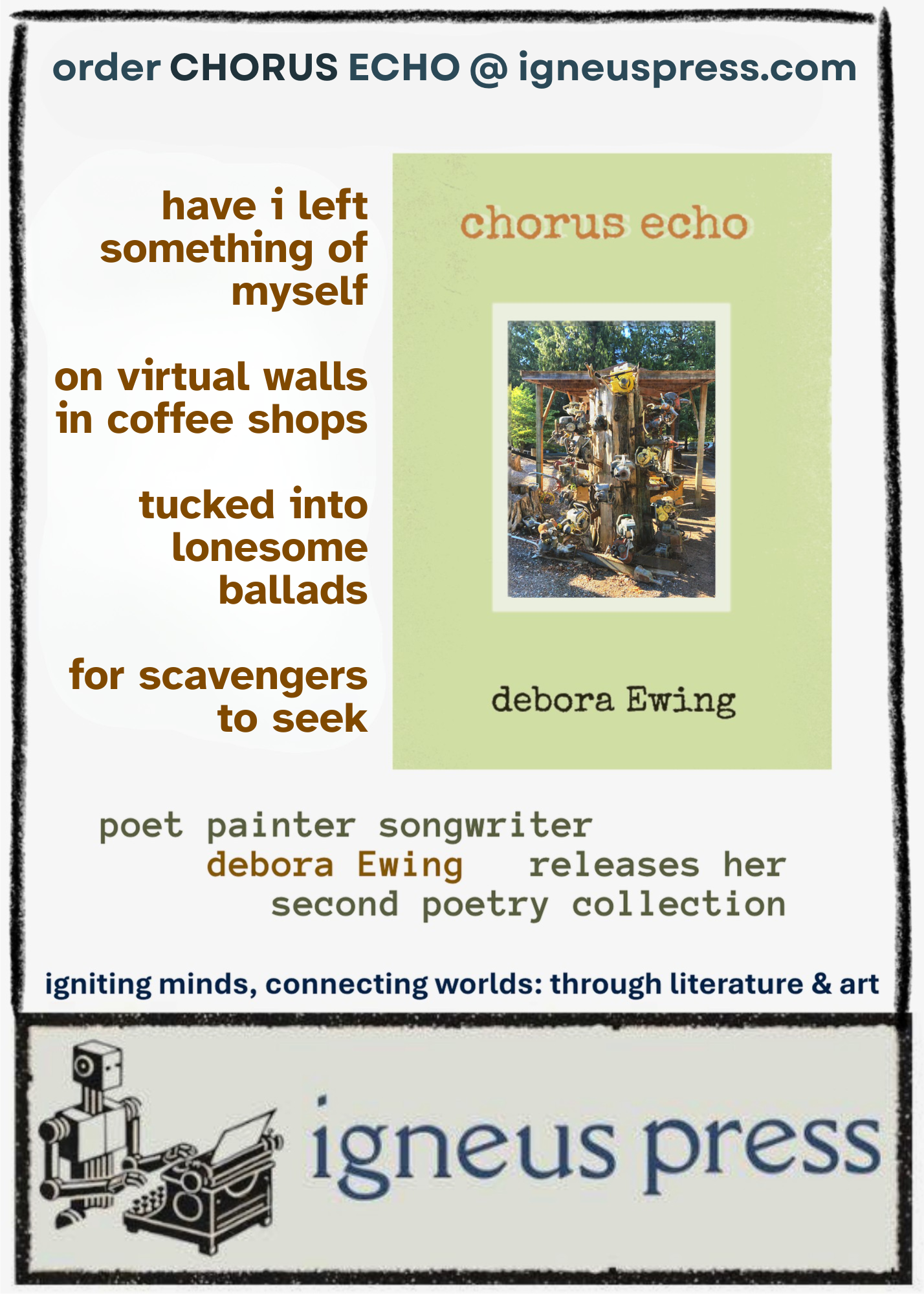

“This Machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender” — carefully lettered on the banjo of epic figure, Pete Seeger. The immortal words in a ring, painted in black around the head of his instrument, like an anthem that pulled itself back from the brink of being too intense, until it became useful again to rally around. It implies but does not explicitly speak about the force that music, as collective action, can take. Music which can be, and often has been, much more direct in its call to activism. I looked at the internet, to find what “scholars” ™ had to say on the matter of the slogan. Most called it “violent” or “militant”. Militant?!?! I guess you could say that, if thoughts and getting people to think are inherently charged and dangerous. But I think they do something far more valuable, they make resistance approachable.

I met Pete Seeger when I was very small (6 years old or so) at my first peace march, when he was out in San Francisco for a demonstration against nuclear proliferation, and for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. He was wry, astute, and friendly to an inquisitive and precocious kid, but he had flint in his eye for the purpose at hand. He was travelling to embolden and light up cities whose people had fallen asleep at the helm. He had a thing he was doing here in CA: visiting his old buddy Faith Petric at her Clayton street San Francisco Folk Club gatherings in her living room, and galvanizing post flower child San Franciscans into action. Lauded as some kind of savior by the other attendees, I think his message, of hard lines and deliberate restraint wrapped in song with an unbendable moral fibre at its core, rang true. His message was of inclusion, and of care, and of “you too can do great things if you’re brave enough.”

And I was surprised at the contrast of celebrated perspectives in those same song session rooms. How could folk music contain such different souls or intentions simultaneously? Well, it did and it does. Because people contain multitudes, and always have. Amid retroactive speculation about a sort of polite nod to political friction being too much in the face of fascism, I remembered to look back with open eyes. There was grit and hardness from one end of the spectrum; at the other, in another room, there was something easy and feel good-ey but light. Love songs, that were just as simple as unexamined love can be.

The stronger position puled toward revolution, and the plights of common people. One end of the spectrum, no less enduring than the ever-present declarations of “loooove”. But maybe more fervent. And I noticed that the moderate position, touted as radical, is nothing of the sort. It’s not a call to do anything harmful, or hurtful, or inciting to physical damage in any way. It’s a sternly worded letter when presented next to the inspirational message painted on Woody Guthrie’s Guitar: “This Machine kills Fascists”, it says. And he meant every word. Each chord, each word, directly stating the hard truths of damage already begun, and the people doing them, named explicitly. Guthrie says, directly in opposition to class eradication in the face of systemic pressure, that the crowd is allowed its anger. He names the violence already begun as violent, and claims the response to violence is about survival.

A musical instrument and its player employ the weapons of words, of psychological effect, and of indirect response. But is a response an escalation? The conversation between folk music icons then takes new shape, while reviewers and historians soften the tone and tenor of the artist in order to be palatable to more communities. Some singers, some writers, take things an additional step, into subversive universes. And the shift in view to one of less intensity re-centers the conversation around the fundamental question of our age. What is “violence”? Does that definition include economic, medical, environmental, gender-based, accessibility, or ideological deprivation? When people are removed from all lifesaving options, have they experienced something we’re allowed to name as “violence”? Does that get to include hate messaging? Is it only limited to when someone speaks or sings, or pushes back? And where in the discourse is any response at all seen as ratcheting up the temperature?

I think Pete asked these questions very carefully, and ignored a certain amount of violence done to him, by establishment studios and industry professionals, by political figures, and arts funders, and by those too terrified to take any responsibility for themselves. (As one example, Burl Ives’ inclusion of Seeger’s name on a list of potential radical Communists forever altered his career prospects and trajectory.) So now, have we come to it again? Who is anti-fascist? Who gets to hold that label? How is it used? Pete instead asked each of his concert goers to consider: “where is your line?” or “which side are you on?”. And how much has to happen for you to find your answer? His music posed a fundamental vision of inclusion into a future that comes after fascism? What happens if there is one? Well maybe we build coalitions and communities underneath and around all the destruction of state-sanctioned dehumanization. Maybe we plan to continue conversations, and coalitions.

Pete Seeger in the 1990s

When I visited the Traditional Music School in Barcelona, a decade ago, I saw newspaper clippings on the walls of press from the shows he nearly didn’t get to perform in, a few dozen years before. He was allowed into the “Kingdom” of Spain, to perform in Barcelona, the birthplace of Anti-fascism, under the condition that he not sing the most subversive of his collected songs… even denuded of the direct calls to action found in Woody’s more intense rhetorical flavor. And so instead, he played the chords… and invited the audience to sing the words over that banjo’s dulcet tones. It became a moment of collective empowerment that galvanized and heartened a new generation of Catalonians, because it left the door open for their own responses, hearts, and intentions for action in the songs, and in the bigger picture. There was room for everybody to sing, and ask the question: where had all the flowers gone, and why? Viva La Quinta Brigada in all of us.

This Machine… Does Things

Number 5 - January 2026