Songwriting Lessons from Neuroscience and International Politics

I studied international politics in college, and one question in particular has always bothered me: when it comes to war, why can’t humans be rational, and simply bargain about what they are fighting for? For example, if Vladimir Putin, in his mind, knows he only has a 25% chance of conquering Ukraine, why wouldn’t he try to negotiate for one quarter of Ukraine’s land? Yes, these theories seem a bit silly, but there is a deeper truth revealed about the human psyche, and why something that makes perfect sense logically doesn’t work out in reality. Academics essentially agree that if every world leader just decided on war by trying to bargain instead of fight, many human lives and resources would be saved. Of course, the science of the brain reveals why this is: the strength of the emotional mind is simply stronger than the more sophisticated judgements of the higher mind. Interestingly, we can apply this knowledge beyond international relations and neuroscience, and even into music.

I studied international politics in college, and one question in particular has always bothered me: when it comes to war, why can’t humans be rational, and simply bargain about what they are fighting for? For example, if Vladimir Putin, in his mind, knows he only has a 25% chance of conquering Ukraine, why wouldn’t he try to negotiate for one quarter of Ukraine’s land? Yes, these theories seem a bit silly, but there is a deeper truth revealed about the human psyche, and why something that makes perfect sense logically doesn’t work out in reality. Academics essentially agree that if every world leader just decided on war by trying to bargain instead of fight, many human lives and resources would be saved. Of course, the science of the brain reveals why this is: the strength of the emotional mind is simply stronger than the more sophisticated judgements of the higher mind. Interestingly, we can apply this knowledge beyond international relations and neuroscience, and even into music.

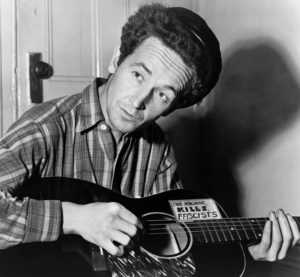

So let’s talk about songwriting. Have you noticed that the most timeless popular songs and genres in the last hundred years, let’s say, have an emphasis on minimalism and simplicity? Yes, classical music will always be revered, but in terms of songs that are loved, many of them are not necessarily academically interesting in terms of chords, lyrics and arrangements. Think about songs like, “This Land Is Your Land.” It consists of three chords, a basic melody and straightforward lyrics. As I try to write great songs, that I can personally love and not just intellectually revere, I’ve consistently found that simplicity is often more difficult than complication. Maybe that’s why in the writing world, editors are often considered above writers? Of course, that’s not to say that being complex is not a positive trait in music – after all, many of the considered greatest albums in modern US history like Sgt. Pepper and Pet Sounds are remarkably complex. However, these albums I believe always prioritize and retain emotional strength, so that any academic and experimental complexities added in addition never come at the expense of the former. Here again we see that emotional strength is the fundamental, and complexity only helps a song if this already exists.

Two Types of Thinking

This distinction between emotion and logic is roughly found in many other fields of inquiry beyond songwriting and international politics. For example, Daniel Kahnman’s famous Neuroscience book, Thinking Fast and Slow, separates the brain’s thinking processes roughly into “System 1” and “System 2” thinking. The first is “fast, intuitive and emotional,” in songwriting, what might be akin to John Lennon’s advice to George Harrison, which was to finish your song in one sitting. The second is “slower, more deliberative, and more logical.” George Harrison and Leonard Cohen’s natural tendencies to stay with a song until it had even the smallest details correct might mirror this style. After all, you may have seen that clip of George trying to get one of the last lyrics to “Something” just right. Meanwhile, John, in his typical more intuitive style, told him just to say whatever came to mind each time until it felt right.

Another scientific experiment tested subjects ability to match colors and numbers effectively, even in confusing combinations. For example, a card with the word “red,” written in a red color, is easy for a reader to identify as red. However, a card with the word “blue” but written in the red color, takes some time for a reader to identify as written in red. What they found was that people were more prone to eating fatty foods, which we normally crave after intensive mental labor, after the second, more confusing task. Of course, it was because the second task required the System 2 thinking that takes a lot more energy than basic instinct. In general, the more recently evolved parts of the mind take substantially larger amount of energy than going off our basic instinct. In the same way, tasks like theoretical mathematics and philosophical discussion take a lot more energy than simply casual conversation.

Songwriters might take a page out of this research by realizing that to appeal to sophistication and academic complexity is impressive but can be exhausting for an audience. That’s not to say that we should aspire to be the Ramones with their brilliant simplicity, but relative lack of academic sophistication and ambition. There is nonetheless a possible lesson to learn that we don’t always have to just impress the listeners with a wide array of rhythmic and chord changes for their own sake.

Of course, artistry for its own sake has value even if an audience isn’t ready for it. After all, on a higher level, what’s the point of creating something that is comforting for where we are at a current moment, but doesn’t inspire us to yearn for more? How would we feel about the Beatles if they had never created anything beyond the early records, where they sang only “I want to hold your hand” and “she loves you”? And how would we feel about the Beach Boys if they never made God Only Knows and Good Vibrations and kept singing about cars, girls and the beach until the end of time? Once again, some sort of balance has to be found, between using rhythms and melodies that are familiar enough for a listener to stay engaged with, and yet has elements of artistry and yearning towards a new frontier that engages the mind and inspires the soul. It’s a hard thing to find this balance. I think one thing that makes a timeless artist is exactly that ability to be on both sides of that coin.