Christine Gunn: Brain, Bow and Paint

in which we talk about art, music, childhood, glial pruning, and inter-brain synchronization

Christine Gunn performing in the FolkWorks private showcase at FAR-West 2025

I first experienced Christine Gunn (along with her musical partner, Reggie Garrett) in the process of helping organize FAR-West 2023. I’d already been a fan of Reggie’s work, but the two together are magical…so I had to find out more about Christine. I found out she painted Van Gogh’s Starry Night on her cello. Yeah, whoa.

Reggie told me I should connect with Christine if I wanted to compare art and music. What I was not expecting was the interweaving of science into this constellation, and neuroscience, no less. These are a few of my favorite things! Turns out this was the conversation I didn’t know I needed.

me: So for you, what came first? Art or music?

CG: I mean, you go back to childhood and I can say they kind of co-evolved. I was always doing artistic projects like you do when you’re a kid. That’s the thing, I just never stopped.

me: Never stopped being a kid.

CG: That’s one way of putting it. I never stopped, but I think even back then when I started music, I didn’t think: “I’m going to do this professionally.” It was just a part of life.

me: How old were you when you started music?

CG: Well, it’s kind of the same with art. I just was always doing it and never stopped. I started playing cello at 10, and I knew I was going to keep playing cello when I got that cello, but I didn’t think, “oh, this is what I’m going to do for a living.” For a living, I was going to be a scientist, but I just knew that I was always going to play cello.

me: Oh, good. So we can loop science into this conversation too.

CG: Sure.

me: I’m excited about that! So I agree: Art starts kind of naturally because when you’re a child and the adults want to keep you occupied, they’ll give you something. Here, scribble on this paper. Make something, just occupy yourself.

CG: Right, but I mean, I don’t know your age, but I’m Gen X, which is like, we were just not really raised. They didn’t even say, here, go occupy yourself. They were just gone. So you occupy yourself.

me: This matches my experience.

CG: I was always doing projects. My carpet when I was a kid was just filled with dried paint and melted crayons… I had a Lite-Brite, but I used to put a piece of paper on the back of it and it would get hot, and then I could melt crayons into the paper. Or if I wanted doll furniture, I would just take a cardboard box and a little knife. I didn’t have an X-acto knife; I’d get a kitchen knife, and I made some really cool little models.

It was the same with music – as a kid, you’re singing all the time and listening to music…my dad had an Ocarina and I figured out how to play that. My sister brought home a violin from grade school when I was still too young to be in orchestra, and I just thought it was magic. I would constantly beg her play “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” again. I couldn’t believe you could just make a melody out of the thing. It was so exciting. That enthusiasm, it just never stopped.

CG: It was a few years later that I got my first cello and I was completely enamored with the sound. I would play the same low C note on the open string over and over. I don’t know for how long because of course your sense of time is different when you’re a child. But it seemed like hours to me. It was just magic to be able to make that sound. And I’ve never stopped being in love with it. Whenever I can, I will sit someone down in front of the cello and just play for them so they can see what it feels like to have that vibration go through them.

me: When inspiration comes to you, is it clearly defined: can you tell immediately “this is going to be art” or “this is going to be sound”?

CG: I’ll get melodies that just kind of come out of nowhere. If it’s in the middle of the night, which is always when it happens, I’ll take out my phone recorder and I’ll weakly try to sing the melody into the thing and play it back later and go, okay, that’s the song to be developed.

For projects, I’ll just get an idea in my head. They evolve, right?

Once I was out just having a moment in the woods one October, taking a ton of pictures, trying to get a different eye. And it wasn’t because I thought, “Oh, I’m going to publish these pictures” or anything. I was just trying to capture that moment.

I took one of those and started playing with it digitally until it kind of felt the way I wanted it. And then I took that and painted it, and then that painting was sitting in my studio one day when the sun started coming through the back. So now I’m going to put lights behind it because that’s what I want to see. So the project sort of evolved for me. And my painted cellos, I wouldn’t think of those as artworks necessarily…

me: Wait, how many painted cellos do you have?

me: Wait, how many painted cellos do you have?

CG: Three.

me: Cool!

CG: Those are exercises in painting, because I’m imitating great works. So I have a Monet and the Van Gogh…

me: I knew about the Van Gogh.

CG: But I’m actually getting into it and looking at it really carefully, making the paint strokes look like the original artist. I still think there’s an art to that even, you know what I mean?

me (emphatically): Yes.

CG: Because I’m creating a thing, but again, it’s not for sale, but because it’s a thing that I want to exist in the world, so I want to make it, but making art is also the process. I get really obsessed too; with that Van Gogh cello, I was trying to pace myself, but I did it all in about 12 straight hours.

me: WOW. so fun. And I’m thinking, when you’re talking about how you pay attention to the minute detail and the process, that’s science leaking into it.

CG: Definitely. It’s color theory and shape and I start to realize: I think only had three colors on this palette.

me: Whoa. I have a three-color paint process.

CG: – and you just mix it all together on your palette, right? Well, take a look at Starry Night some time. I used three, maybe white, but not black. It was just such a dark blue. So I get into the minutiae and the detail of how does this work and the shape of it. So that’s kind of a science too.

me: It’s also what science does – breaking it down into the smallest possible measurable amount. I work with a bunch of scientists who use poetry to convey the beauty of what they do, hoping to help people understand it.

CG: I think of Carl Sagan as the ultimate poet-scientist. “A still more glorious dawn awaits, not a sunrise, but a galaxy rise. A morning filled 400 billion suns…

me: …and who doesn’t want to be made of star stuff?

CG: The best way to describe stuff.

me: It helps you understand how we all are connected, and that’s what music does, I think more so than visual art. Visual art, to me, feels like it’s more of a one-on-one relationship between yourself and the piece. Music feels more connective: to the piece and everyone else, too.

CG: Yes, definitely. My field of interest in science is cognitive neuroscience, specifically interactional synchrony and hyper-brain networks. Music is something that feeds into synchrony, when brainwaves start syncing up and they act like a single large brain.

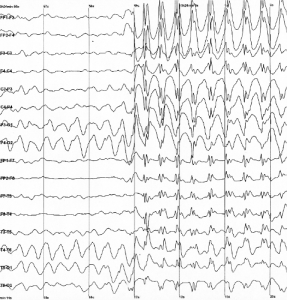

Epileptic spike and wave discharges monitored EEG (from Wikipedia Commons)

The studies that have been done connect EEGs to a guitar duet to see how they play together. And it acts like a single brain. One person is like a leader, with prefrontal cortex kind of waves, and the other one follows. And then they’ve done studies where they hook up an entire audience to EEGs, and they’re watching a live band. And as people kind of get into it, it starts getting those synced brainwaves. So again, it’s acting like one big brain.

As a control, they’ll do the exact same performance, but it’s recorded instead of live, and it doesn’t have that same level of synchrony. So live music literally turns people into a giant singular consciousness, which is so –

(both of us): Amazing.

CG: And when I go back to school, that’s what I would like to be focusing on. When my kids grew up and moved out, I went back to school and got my bachelor’s in integrated chemistry and biology, and I thought, okay, now I’m just going to pursue this for a while. But at the end of the last quarter, I just wanted to play music again for a little.

me: That makes sense. I think once you have your brain loaded with all that, and then you’re playing music to relax, it’s going to probably synthesize some of what you learned.

CG: When I do go back to school, I’m going to balance it better with the music. I was hardly playing at all while I was in school. I probably would’ve enjoyed myself more if I would’ve stopped and played music every once in a while; it’s like breathing to me. At no other point in my life did I just stop.

me: The different parts of your brain need exercise too. I hate using the term muscle memory for brain, but it’s the term everybody understands. Is there a different term for that for the brain?

CG: Yeah, definitely. If you’re talking about the reuse of a neuron to make a connection, that’s myelination. And the more times you go over a specific connection, it creates those glial cells that basically stay over the outside of it. That creates passageways between the synapses. And the more that you do something, the more myelinated it is. And you also have glial pruning, right? When you’ve been busy working on one thing and you’re totally overwhelmed and not functioning, to switch gears allows pruning of the things you’re not using. You could kind of imagine it if you were crocheting and looked behind you to see all the yarn was getting knotted up. It makes it a lot harder to move fast. I don’t know if you crochet or not.

me: It’s one of the things I suck at, but I do understand the concept completely.

CG: Okay. So imagine if while you were working, your yarn was getting all tangled up and all you had to do is go to another project and the yarn would magically untangle itself.

me: Oh God. That’d be great!

CG: It doesn’t really work as an analogy, because yarn doesn’t do that, but you picture it, right? That’s why it’s really important to step away from things because that’s exactly what’s going on. You’re getting yourself so tangled up, it’s not really effective use of your brain space.

me: Yeah, it makes sense to me – a lot.

CG: I’ve heard, I don’t know if it’s apocryphal or not, but I’ve heard that Einstein, when he would get stuck on a particularly rough problem, would go play his violin, and then when he would come back to it, it would be easier to work out.

me: That makes sense.

CG: So yeah, when I go back to academia, I will keep the cello going.

me: So you’ve got three cellos that you have painted. Do you pay any attention to how the thickness of the paint is going to affect the sound of the cello?

me: So you’ve got three cellos that you have painted. Do you pay any attention to how the thickness of the paint is going to affect the sound of the cello?

CG: Well, I wouldn’t paint a good cello. One of them is the same plywood cello that I had when I was much younger when I used to play at the Pike Place Market. It’s got this great bassy tone. It’s been broken a bunch of times. And that was the first one – that was the Monet. I painted it with a friend, actually. And then the Van Gogh, I thought would be great to get another cheap cello that I could electrify, but it’s built poorly. I got it for like 60 bucks at a pawn shop, and it’s almost not playable. It really isn’t playable. So it’s really just a display piece.

The Klimt cello – I was going on tour with the Chautauqua group – they travel around to small towns and bring a big performance, and there’s a marching band. And they wanted me to play cello in the marching band. So I got a little three-quarter size cello, actually my oldest child’s cello when they were very young. They never stuck with it. So it was just a cheap Chinese three-quarter size cello. And I think, oh, this will be small enough that I could use in the marching band.

The Klimt cello – I was going on tour with the Chautauqua group – they travel around to small towns and bring a big performance, and there’s a marching band. And they wanted me to play cello in the marching band. So I got a little three-quarter size cello, actually my oldest child’s cello when they were very young. They never stuck with it. So it was just a cheap Chinese three-quarter size cello. And I think, oh, this will be small enough that I could use in the marching band.

Then I wanted to make it another art cello anyway. I thought I would go with gold to look good with all the brass – that’s why I went with Klimt. It’s fine to play. It never sounded very good anyway.

I would never paint a fine instrument. Obviously that’s going to affect the sound, but these are so sh*tty (pardon my French.)

me: But you do still play them sometimes, depending on the situation.

CG: I do. The Monet is kind of my campfire cello, although it’s needed some repairs; the neck is kind of broken again. And yeah, the Klimt is specifically for marching band work.

me: Well, I hope you find some more opportunities to do that, to march in a band with a cello, because that’s pretty awesome.

Is there something you’d like to learn creatively that you haven’t started yet? What’s fascinating, but still on the horizon?

CG: Let’s see. When I get interested in stuff, I just pick it up. So I’m trying to think if there’s something that I haven’t done yet that I would like to do. I’ve done metalsmithing. I’ve done a lot of fiber arts, knitting and crochet and macramé; wire working with jewelry, painting. Oh, sculpture. It would be nice. Or I kind of like to get into ceramics, actually.

me (ebullient): I love ceramics so much because dirt is one of my favorite things. I went to college as an adult and took ceramics every semester. Sometimes I was the only person in my class. Yeah, it’s yet another thing you can do with dirt, and it’s awesome.

CG: Isn’t going back to school as an adult the best? That’s what I did. I was 47 when I went back for my degree. I was worried at first that because I was going to school with people that were younger than my kids, that they were going to be like, “What’s this old lady doing here?” But they were really cool too. All the younger students, I think they wanted to work with me because I was a good bridge to the professor – a professor would be my peer, and they felt safer sitting at my table.

At some point I will. Eventually I’ll get a kiln out here, I’m sure.

me: …because the logical next step is to own all the equipment.

Do you have any topics that you would like to platform, any statement you’d like to make about music or art, or really anything?

CG: Here’s one that I’ve been mulling around lately. Because you do this: You’ll have a thought that’s kind of a filter through which you’re looking at the world in that moment.

me: Yes, I get that.

CG: So again, from a neuroscientific perspective, but also as a musician and a storyteller and an artist, the fact that we as humans view the world as a singular narrative. You look at your life as a story, and it’s all about context. You take moments from your life and you’ll string them all together, and it’s like a dot-to-dot picture. But you could just as easily take completely different moments and make a completely different picture.

And the fact is that we see things as these simple narratives. It’s just not actually how things are; it’s a turbulent system. It’s just the way our brains interpret the data. Any time you’re interacting with somebody, or in any situation, you know that your brain is trying to put it into a story.

me: we are pattern extractors.

CG: Right? I’m thinking of – specifically right now – not just the patterns, but the storytelling part of it.

And you tell yourself a story: Mom was the good guy, and dad was the bad guy, and this is what happened. But it’s so much more. I think that the way people are reacting to the input that they’re given…they’re easily manipulated because people know how to tell the story. I think that as a storyteller, as a musician, as an artist, as a person that’s just getting older, I think as you’re looking at the story of your life, you realize that it doesn’t have any meaning as such.

me: Right? I get really bogged down with that sometimes, when I get to that part of my story where there’s not a real meaning. But you can go back and choose different points, and that makes a different narrative. And none of them are wrong. They’re all true stories; it just depends on how you connect the dots.

CG: Exactly. I think as we get older too, it’s easier to just sort of function in reality as it is because you’ve seen things go up and you’ve seen things go down. What it felt like when you were in the middle of something – what you thought that narrative in that moment was about turned out to be completely insignificant in the grand scheme of things.

So turn that to the current moment: Go, “Okay, whatever is going on in my life in this moment, how much significance is this going to have to me in five years? Can I alter that based on my decisions right now, can I change the significance of this moment? Can I use whatever it is and create the narrative that I want to create?”

And in that way, though, a lot of my life right now is just enjoying it while I’m here. Also in that vein, in a weird way, memories are more important than experiences.

me: There’s something that gets lost. There are things that get pruned.

CG: Yes. Allowing your memory to be the thing that encapsulates that moment allows you to create a narrative around it too. And it gives you a different kind of significance.

me: And that’s where the art comes from. When I want to try and convey the feeling I had from being there in that moment – if I want to paint that, it’s going to come out as something that affects the next audience differently. Now it’s been translated into a different medium.

CG: We were talking about the difference between the visual art and the music thing. I like the magic of a musical moment that is gone once it’s happened. It’s like a sand painting. It’s the process, and then whew, you blow in it and it’s all gone. All that’s left is just in the memories of the people that got to experience that.

me: And maybe that’s how visual art gets to be more isolated and one-on-one: because it’s static. It doesn’t change. Your interpretation of it can change; your perspective, your angle, but it stays solid. It is what it is once you let go. Although, I’m hesitating because sometimes there are paintings that I really have to promise myself that I am not going to work on it anymore, because otherwise…I found out songs are like that too. You can keep tweaking forever.

CG: For me, creation is kind of a selfish act. There’s a moment that I want to exist in the world, or a song that I want to exist or a thing that I want, and so I make it, and that’s been since I was a kid. Like I said, that I wanted doll furniture. I would make the doll furniture. I wanted the art to exist, and so I made it. I wanted painted cellos, so I painted the cellos. A song that I want to hear: Reggie and I just wrote a song.

I wanted something that specifically says, “the world’s going to just keep spinning, so just all I can do is enjoy the life that I have right now.” And so we wrote that song. I wanted it to exist. So for me, it’s not just about an obligation, or…I don’t know what inspires most people, but I think for me, it’s like I want something to happen, and so I make it happen.

me: It’s interesting you say the word “obligation,” because it feels like that to me. Sometimes I feel like there’s something that I can perceive and other people can’t. And so it’s my job to bring it into a format that they can see.

CG: I do understand that. One of my main focuses with academia is I thought, well, I have something to contribute. I have a perspective and I should do that. But it’s very freeing when I pull back and I realize that these studies were happening, whether I was contributing to them or not.

me: I think it was in a songwriting class where somebody said: “Don’t worry if you’re not able to catch the muse, because somebody else will.” You can move on to the next one. It’s really okay.

CG: Exactly.

me: So how did you end up meeting Reggie Garrett?

CG: We ran in a lot of the same circles 30 years ago, and we’d seen each other play, and he was doing a recording (in ’93 or ’94) with people I knew. They said, “Hey, we should get cello on this. Let’s call Christine.” And so that was the first time we actually played together, but we didn’t really play together. I just did some recording on his CD. We’d crossed paths every once in a while over the years. And then he moved to Olympia. I moved to Olympia from Seattle 19 years ago. He moved down a couple of years ago.

A mutual friend of ours I invited to a party…I don’t know if you remember Trillian Green…

This was a band I had many years ago that was quite popular. We have reunion shows every once in a while. So we were having a concert at my house, and I invited this mutual friend who said, “Hey, I’ve been playing with Reggie Garrett. How about we come and do a set?” Yeah, sure. So Reggie came out to my party and he played, and it was wonderful.

He was reminded of my playing, because I played with my band, like, “Oh, yeah, those guys are really good.” I’m like, “Yeah, you’re really good.” The mutual admiration, that was it. But then about a year or so later, he had been given a concert at a local venue called Traditions. He thought, instead of getting his whole band to come down from Seattle, see if Christine wants to play.

And I did. Yeah, definitely. So he gave me about 30 songs to learn in about a month, which is a lot, but I really wanted to do it justice. The thing with Reggie is his singing and his playing are so beautiful. He’s such a good songwriter, and his voice is just mesmerizing.

me: Yes.

CG: I felt like if I was going to play with him, I wanted to actually add to it and definitely not take anything away. So I really did my homework. I wanted it to feel good. And yeah, the first couple of times we practiced together, I think we both could say, “Oh, this is really good. This is something special.” Then we played that show, and we knew we were going to keep playing after that. When you’ve got good musical chemistry with somebody and there’s nothing impeding it, you just go for it.

me: It’s magic. Yeah.

CG: Oh, yeah. No, we can definitely feel it. I mean, the cello works so well with his voice and his playing is just beautiful. I like a simple setup like this. The duet is nice. It’s easy to connect with just one other person that way musically.

Garrett & Gunn’s new album, The Road Taken, is available on Bandcamp. Get some of that magic for yourself. I believe I even spy the Klimt cello on the cover. Christine designed that cover.

Here’s a live recording of Garrett & Gunn performing “A Place in This World” from the new album. Please enjoy.