Woody Guthrie’s Home Town Lynching

A Bridge Over Troubled Water

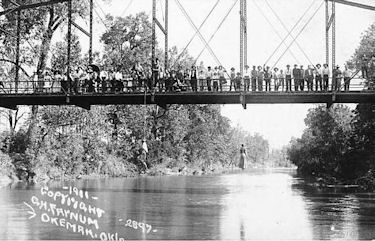

Okemah, Oklahoma was the town that Woody Guthrie described as, “one of the singingest, square dancingest, drinkingest, yellingest, preachingest, walkingest, talkingest, laughingest, cryingest, shootingest, fist fightingest, bleedingest, gamblingest, gun, club, and razor carryingest of our ranch and farm towns, because it blossoms out into one of our first Oil Boom Towns.” He left out one small detail. It was also one of the lynchingest—the town that the year before he was born hosted one of the more horrific lynching parties that had ever made its way north of the Mason-Dixon line. Captured in a news photo of the time forever and for all to see, “our town” seemed to have nothing to hide—not a flicker of shame colored the glowing faces of the frenzied lynch mob of onlookers and supporters.

Okemah, Oklahoma was the town that Woody Guthrie described as, “one of the singingest, square dancingest, drinkingest, yellingest, preachingest, walkingest, talkingest, laughingest, cryingest, shootingest, fist fightingest, bleedingest, gamblingest, gun, club, and razor carryingest of our ranch and farm towns, because it blossoms out into one of our first Oil Boom Towns.” He left out one small detail. It was also one of the lynchingest—the town that the year before he was born hosted one of the more horrific lynching parties that had ever made its way north of the Mason-Dixon line. Captured in a news photo of the time forever and for all to see, “our town” seemed to have nothing to hide—not a flicker of shame colored the glowing faces of the frenzied lynch mob of onlookers and supporters.

That they have practically to this day never acknowledged their only famous native son speaks volumes about how far removed in spirit, culture and values Woody Guthrie was. Somehow he became everything his home town was not: a social outcast who embraced all races, creeds and religions, who when he was asked to indicate his religious preference upon admission to Greystone Hospital for the Huntington’s Disease that would eventually take his life put down “All.” When challenged to be more specific Woody added, “All or none.”

In stark contrast, this pristine home town example of Strange Fruit qualifying the high-toned inclusiveness of whether this land was really made for you and me does not even rate a mention in the vast array of workshops and encomiums that fill out the USC Conference on the Woody Guthrie Centennial; nor is it the subject of any of the Grammy Museum programs on the same theme; nor does it invite the scrutiny of any similar programs, conferences and concerts featured on the massive website. This is the Centennial story the big guys missed.

But it certainly did not escape Woody’s attention. His song, Hangknot, Slipknot, reveals a firsthand knowledge of some of the seedier aspects of his upbringing.

Woody simply had no patience for the legacy of racism derived from what historian C. Van Woodward so memorably termed “The Peculiar Institution” of slavery. When he brought his black friends and fellow musicians Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee to a fundraiser for American troops during WWII, only to be told that his friends would need to enter through the back door, Woody promptly strolled up to the refreshments table, grabbed the edge of the table cloth, and ripped it out from under the Champagne bottles and fruit and salad bowls decorating it, before picking up a gallon bottle of wine, circling it threateningly around his head like Will Rogers rolling out a lariat, and telling the assembled crowd, “This war against fascism has got to start right here—in our own back yard.” Then Woody, Sonny and Brownie all left together—through the front door.

To have come from Okemah, Oklahoma with these beliefs was an extraordinary departure, knowing the odds were all in favor of him perpetuating the racism that led to the lynching of both Laura Nelson and her 14-year old son Lawrence W. Nelson.

The following account of this dark chapter in Oklahoma history is quoted from the exhibit Without Sanctuary, the source for virtually all of the versions available on the Internet:

“America’s newspapers, while decrying the savage brutality of the lynch mobs, in general gave only loosely detailed, ultimately sympathetic reports that absolved the communities and officials of any collusion or guilt.

The following account of the lynching of Laura and L. W. Nelson was drawn from Oklahoma papers: A teenage boy, L. W. Nelson, shot and killed Deputy George Loney, whose posse was searching the Nelson cabin for stolen meat. Laura Nelson, trying to protect her son, claimed to have shot Loney. Her innocence was determined weeks before the lynching. The boy’s father pled guilty to stealing cattle “and was taken to the pen, which probably saved his life.”

Forty men rode into Okemah at night and entered the sheriff’s office unimpeded (the door was “usually locked”). The jailer, a man named Payne, lied that the two prisoners had been moved somewhere else, but when a revolver was “pressed into his temple,” he led the mob down a hall to the cell where L. W. Nelson was sleeping. Payne unlocked the cell, and they took the frightened boy, “fourteen and yellow and ignorant,” and “stifled and gagged” him.

“Next they went up to the female jail (a cage in the courthouse) and took the woman out.” She was “very small of stature, very black, about thirtyfive years old, and vicious.” Mother and son were hauled by wagon six miles west of town to a new steel bridge crossing the Canadian River “in a negro settlement,” where they were “gagged with tow sacks” and hung from the bridge. “The rope was halfinch hemp, and the loops were made in the regular hangman’s knot. The woman’s arms were swinging at her side, untied, while about twenty feet away swung the boy with his clothes partly torn off and his hands tied with a saddle string. The only marks on either body were those made by the ropes upon the necks. Gently swaying in the wind, the ghastly spectacle was discovered by a Negro boy taking his cow to water. Hundreds of people from Okemah and the western part of the country went to view the scene.”

“Sheriff Dunagan thought at first that negro neighbors of Nelson’s had come and turned them lose.” “No attempt to follow the mob was made.” “The work of the lynching party was executed with silent precision that makes it appear as a master piece of planning.” “While the general sentiment is adverse to the method, it is generally thought that the Negroes got what would have been due them under process of law.”

The story first came to my attention through the chance purchase of a book called, America’s Children by Kathleen Thompson and Hillary Mac Austin, with a poignant forward by Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis. It is jam-packed with photographs of children from every walk of life and period of modern history, and as is obvious by now, is no airbrushed portrait of our country’s failings—even including the famous posthumous photograph of the murdered Emmett Till, lying in his casket in Chicago—the photo his mother wanted America to see so we would know what happened to a black boy in Mississippi on August 28, 1955.

It was that photograph that shook Rosa Parks to the core, and made her determined to do “something” to change her society. A bare three months later, on December 1, she refused to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, and launched the Civil Rights Movement. But I had seen that picture many times, and so was not as shocked as I should have been to see it here.

The photograph of the lynching was another matter—due to that familiar, iconic place name where it happened; the cognitive dissonance—what literary critic Kenneth Burke described as a “perspective by incongruity” between the image and the setting left me shaking my head. How could Woody Guthrie, I wondered, have come from here? Was this Woody Guthrie’s America?

And then it hit me: not just Woody Guthrie’s greatest song, but his entire body of song, his enormous symbolic act (another of Kenneth Burke’s wonderful terms) was an act of soul-searching defiance—a counterstatement, yet another Burkeian term—against precisely this nightmare version of America that he was born into. A bridge over troubled water if ever there was, this was Woody Guthrie’s introduction to the land he would later redefine as “made for you and me.” One hundred years later, we still need his re-vision.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com He has a Ph.D. in English.

Woody Guthrie’s Home Town Lynching

A Bridge Over Troubled Water