WHEELS OF THE WORLD: IRISH TRAD RECORDINGS

Wheels of the World:

How Recordings CHANGED IRISH TRADITIONAL MUSIC

9/16/2020

(Published with permission in “Wheels of the World: How Recordings of Irish Traditional Music Bridged the Gap Between Homeland and Diaspora.” Journal of the Society for American Music 4:4 (2010): 437-449.)

In the past century, Irish and Irish American commercial recordings have had a major impact on Irish traditional music. Early U.S. wax cylinder and 78 rpm recordings were sent across the Atlantic, influencing the playing styles, performance practices, and repertoire in Ireland. More important, the multiple exchanges of music from a variety of geographic regions made vital a network of links between musicians in Ireland and across the diaspora, which has enabled a more global conception of the art form.

In the past century, Irish and Irish American commercial recordings have had a major impact on Irish traditional music. Early U.S. wax cylinder and 78 rpm recordings were sent across the Atlantic, influencing the playing styles, performance practices, and repertoire in Ireland. More important, the multiple exchanges of music from a variety of geographic regions made vital a network of links between musicians in Ireland and across the diaspora, which has enabled a more global conception of the art form.

Some of the recordings that first spurred this network featured fiddlers Paddy Killoran, James Morrison, and Michael Coleman; uilleann pipers Tom Ennis and Patsy Touhey; and flute player John McKenna. These influential musicians were recorded in the early twentieth century on the East Coast of the United States on both wax cylinder and 78 rpm records, which were distributed through both commercial and (to a much lesser extent) informal peer-to-peer networks.1 The recordings of these master musicians arrived in an Ireland immersed in a nationalistic folk revival, and quickly became coveted cultural commodities throughout Ireland and the diaspora. The global impact of these recordings brought the Irish diaspora into the continual negotiations among musicians over ideas of tradition and authenticity, and created a vibrant trade route of music, history, and cultural change.

The idea that a form of traditional music has been commodified and exchanged is certainly not unprecedented: Irish music is an oral tradition that quickly incorporated and subsequently relied upon multiple forms of technology to span great geographic distance as players developed traditional performance practice and negotiated ideas of orality and authenticity. Considering that Ireland’s recent history of hardships, forced emigration, and nation building coincided perfectly with the dawn of the Recording Age, such an odd paradox between oral tradition and the technologic became quite necessary for the continuation of the tradition. Unlike other genres of music that have used recordings to recapture repertoire or style through secondary orality, these early recordings allowed those on the periphery of Irish music to act as vital cultural agents and engage with developments in the larger tradition through mediated oral dissemination.

Irish Music in Wax: O’Neill, Touhey, and the First Transatlantic Swaps

The first cross-Atlantic transfer of recorded Irish music originated with Francis O’Neill—Chief of the Chicago Police Department, Irish music enthusiast, and close friend of master uilleann piper Patsy Touhey. Touhey had often visited O’Neill in Chicago and had tested an Edison phonograph machine at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair while performing in the “Irish Village.”2 Living in New York in subsequent years, Touhey must have taken notice of the potential market for recordings of his playing, for on 18 May 1901, the following advertisement appeared in The Irish World:

IRISH BAGPIPES ON THE PHONOGRAPH. ORIGINAL Phonograph Records of the Irish pipes made to order by the BEST IRISH PIPER IN AMERICA. ONE DOLLAR EACH. TEN DOLLARS per DOZEN. Send for catalogue of 150 Irish airs, Jigs, reels, hornpipes, etc. P. TOUHEY, 1388 Bristow Street, New York City.3

How many wax cylinder recordings Touhey cut through this method cannot be determined, but he apparently made them in his home on a machine purchased for just this purpose. Some of these cylinders are still in existence, held in the UCC Library of University College Cork and the Ward Irish Music Archives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

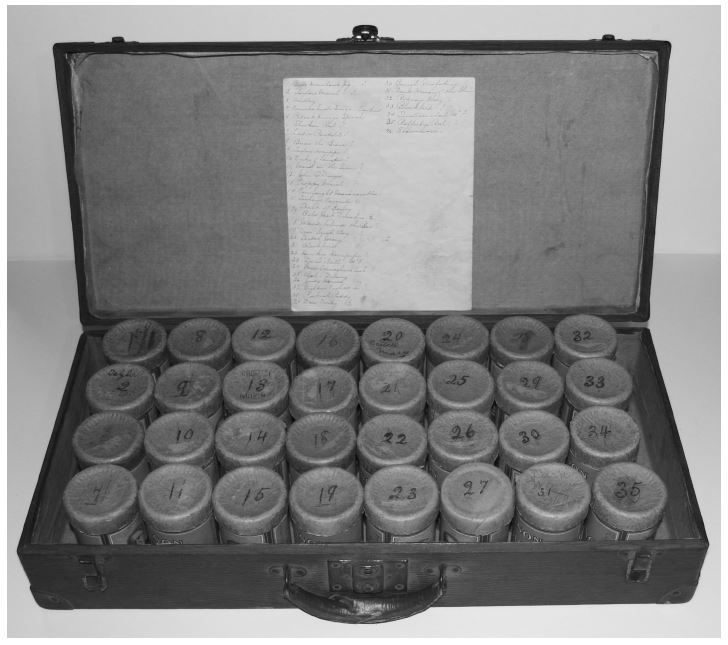

O’Neill wax cylinders of piper Patsy Touhey and others recently discovered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Courtesy of the Ward Irish Music Archives, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

O’Neill wax cylinders of piper Patsy Touhey and others recently discovered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Courtesy of the Ward Irish Music Archives, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.It is unclear whether Touhey himself shipped any of his own cylinder recordings to Ireland, but Capt. Francis O’Neill, a devoted fan of Touhey’s, sent a large quantity of these recordings to colleagues in Ireland. In a letter to William Halpin of County Clare, Capt. O’Neill wrote about one of his first musical parcels sent to Dr. Reverend Henebry in Waterford:

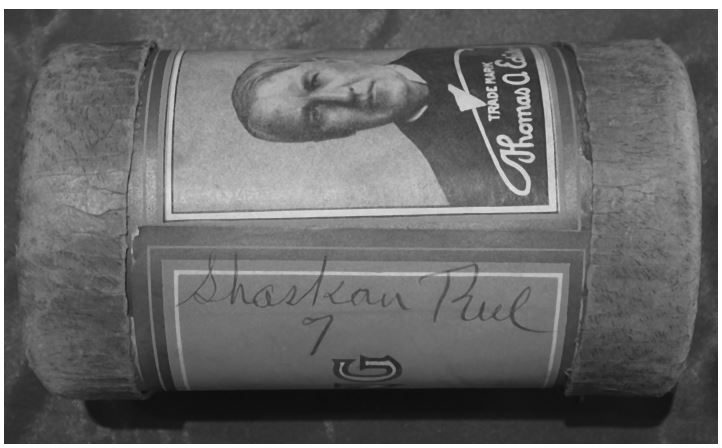

O’Neill’s recording of the Shaskeen Reel, played by Patsy Touhey. Courtesy of the Ward Irish Music Archives, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

O’Neill’s recording of the Shaskeen Reel, played by Patsy Touhey. Courtesy of the Ward Irish Music Archives, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.As a Christmas present which was sure to be appreciated, I forwarded in 1907 to Rev. Dr. Henebry, at Waterford, Ireland, a box of Edison phonograph records which Sergeant Early generously permitted me to select from his treasures. Among them was The Shaskeen Reel played by Patrick Touhey.4

The above mentioned parcel marks one of the earliest instances of the trans- Atlantic exchange system. This underground network of musicians and enthusiasts traded audio recordings through lines of friendship and familial ties, usually surrounding patterns of regional musical interest or common instrument. Capt. O’Neill was one of the leading exponents of this systemin the early days, though his letters also mention receipt of cylinders and 78s from a friend in Ireland. Although these first recordings were produced in the home, rather than in the studio, this trend quickly changed as U.S. recording companies saw the potential market for such ethnic records.

Recording Companies and the Ethnic Market

In the early days of sound recording before the turn of the millennium, record companies were eager to sell big-ticket phonograph cabinets to the general public, often promoting the relatively inexpensive 78 rpm records as “loss leaders” toward such larger purchases. The market quickly took notice: In 1897, Edison Home Phonograph machines were selling for $40, and the year 1899 saw 151,000 phonographs manufactured in the United States.5

Initially, the industry focused on marketing these cabinets to the U.S. middle class, but as the industry tapped out this early market demographic, companies began to introduce improved versions of the gramophone designed to encourage owners to upgrade, while fresh attention was paid to creating new markets. By 1910 recording companies had noticed that the greatest potential for new gramophone sales was in ethnic neighborhoods,6 and by the 1920s the industry had turned a good deal of attention toward established immigrant communities: “Columbia was probably the first national American firm to consciously aim an elaborate ethnic catalogue at its foreign customers. Its 1906 catalogue offered musical records in twelve languages, and within three years the company had issued two additional sets of catalogues for immigrant audiences.”7

As can be seen in subsequent issues of the trade journal Talking Machine World, by the close of 1926 ethnic recording was fully established, and regional record distributors were being encouraged to market within immigrant communities:

Few people are more interested in music and entertainment than those hardy foreign-born Americans who constitute so large a portion of the population of the average town or city, and . . . although they may live thriftily in many ways, music plays an important part in their lives and they spend annually large sums of money for this entertainment. Ordinary sales methods do not always reach this class of population. They group together and keep to their own language. Their purchasing of an article is oft-times stimulated by the experience of friends.8

Columbia, in particular, was quick to tout successes in the Irish community, particularly in urban centers on the East Coast:

The company is quick to release hits and it has just issued a remarkable Irish and French catalogue. . . . It is no wonder that the company is adding new accounts each week to its list of Columbia dealers. New England’s own Irish entertainer, Shaun O’Nolan, has just approved the test records of six of the recordings that he recently made at the New York laboratory. These records will shortly be released. Twenty-five new dealers now carry the complete Irish catalogue.9

The age of ethnic music recordings had arrived, just as Irish America was striving to throw off the stigma of recent immigration and establish itself as middle class.

Eastern European communities in the United States had proven quite lucrative for the record companies as they marketed to cultural pride. Not lacking such pride, the Irish community was clamoring for records of its own music. Ellen O Byrne, a native of County Leitrim, may have provided the final push to bring the recording companies to the Irish market. O Byrne had opened a store in New York City in 1900 at 1398 Third Avenue.10 She stocked the shelves with—among other things—musical instruments and recordings of Irish musicians such as legendary operatic tenor John McCormack (1884–1945). Irish music was in great demand, yet there were very few records available and no instrumental music. The store had stocked early Edison wax cylinders (by lackluster piper James McAuliffe and others) and Gennett 78 rpm records, but they were always in short supply. In an interview with Mick Moloney, Ellen’s son, Justus O’Byrne DeWitt, explained the situation with recordings of Irish-themed songs: “The Gennett company was willing to make records for anybody at that time while some of the other companies weren’t. . . . Now when Gennett stopped making Irish records, my family was at a loss for new Irish records.”11

With her customary entrepreneurial spirit, Ellen O Byrne became the driving force behind the first major label’s recording of instrumental Irish musicians. Her son explains:

Irish people were always coming in and asking for old favorites like “The Stack of Barley.” Well, she’d no records to give them because there weren’t any. So she sent me up to Gaelic Park in the Bronx to find some musicians. There was always music there on Sundays. Well, I found Eddie Herborn and John [James] Wheeler playing banjo and accordion, and they sounded great. So my mother went to Columbia, and they said that if she would agree to buy five hundred copies from them they would record Herborn and Wheeler. She agreed, and they both recorded “The Stack of Barley,” and the five hundred records sold out in no time at all.12

Herborn and Wheeler were recorded on 15 September 1916 in New York, and, as agreed, Columbia pressed five hundred copies for Ellen O Byrne.13 This first pressing marked the beginning of an era in which Irish instrumental musicians in the United States were being recorded, and in which the resulting 78 rpm discs, and the more expensive cabinets and players, could be marketed to Irish American communities. The next few years produced a few very influential records, including those by Tom Ennis (Victor, 1917) and P. J. Conlon (Columbia, 1917).14 After a few dozen Irish pressings, the Okeh recording label was the first to dedicate a portion of its record numbering matrix to an Irish series, their 21000 series. Columbia followed in 1925 with its 33000-F series; Victor dedicated its V-29000 series to Irish music in 1929, and Decca later established its 12000 series.15

As the various recording companies began to develop their ethnic markets, talent scouts would take the opposite approach to that of Ellen O Byrne, who had recruited musicians solely based on ability. Instead, record companies recruited popular instrumentalists with a proven reputation in the dance halls and on the concert stage. Fortunately, the standard of musicianship in the dance halls was tremendously high, and the performers recorded were usually (but not always) at the higher levels of the tradition.

By the 1920s, the recording companies had proved that Irish music would sell. By far the most popular recordings were songs on Irish themes sung in English. John McCormack had become a household name for his recordings of “Mother Machree” and “Kathleen Mavourneen” and is often said to have been the first million-record seller. German American accordionist John Kimmel had recorded a number of Irish tunes for Zonophone in 1904 and 190516 and for Victor Talking Machine Company in 1907,17 and O Byrne had convinced Columbia to record Herborn and Wheeler in 1916.

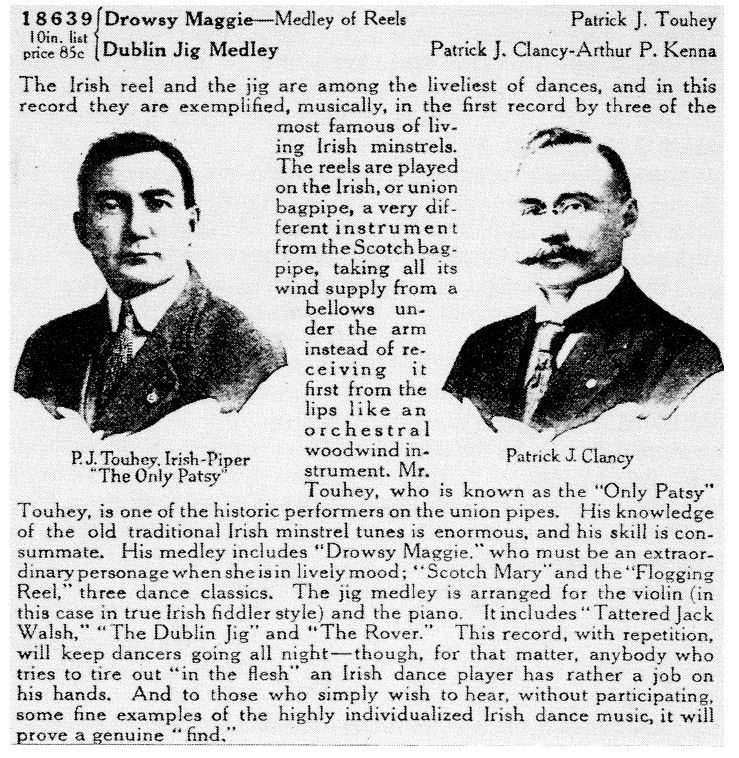

After having rejected at least one offer, piper Patsy Touhey finally signed with Victor and recorded his first record in New York in 1919. The 78 was released in 1920 and advertised in the February issue of the Victor Records supplement as “one of the historic performers” of the “old traditional Irish minstrel tunes”.18

The February 1920 issue of the Victor Records supplement, which featured a new recording by Patsy Touhey..

The February 1920 issue of the Victor Records supplement, which featured a new recording by Patsy Touhey..After these initial pressings, a wide variety of labels began releasing Irish instrumental recordings. According to S. C.Hamilton, “There were around 40 companies that released recordings of Irish music between 1899 and 1942. As the three major producers, around 40% of total releases were for Columbia, 18% for Decca, and 16% for Victor.”19 Of these releases, 47.7 percent were songs, and 53.3 percent were instrumental.20 For perspective, sales figures in the larger U.S. market had been increasing each year, especially in the postwar years, until the Depression: Roughly three million cylinders and discs were sold in 1900, which increased to 140 million in 1921.21 Phonograph production also increased dramatically over these years. The year 1909 saw the production in the United States of 345,000 gramophones; 514,000 were produced in 1914 and 2,230,000 in 1919!22

Reception in Ireland

A number of major social and political movements collided in the first decades of the twentieth century to allow Irish recordings a chance to flourish and become essential to a dialogue about traditional music on both sides of the Atlantic. Hibernian politics saw the formation of the Gaelic League in the late nineteenth century, the 1916 Easter Uprising, and the creation of the Irish Free State in 1921. Post-Famine emigrants from Ireland had prospered in the United States in the late nineteenth century. Economic success, ethnic pride, continuing immigration, and a strong sense of community spurred an early-twentieth-century boom in Irish American dance halls—a period later called the “Golden Age” of Irish American music and dance. The advances in recording technology, the number of recording studios in the New York City area, and the push by recording companies to tap ethnic markets facilitated widespread recording of these musicians and a resurgence of interest in Irish folk music. Finally, with economic security, nationalist pride, and aspirations for middle-class status and its trappings, Irish Americans were hungry for records of their own music:

The boom economy of the 1920s in America meant disposable income to purchase records and an increased interest in music. A new invention, the windup gramophone, became omnipresent in households in both America and Ireland. It seemed that every Irish household, no matter how poor, had a gramophone and a collection of 78 rpm records of Irish music, which was being recorded almost exclusively in America at the time.23

The new leap in recording technology and the U.S. commercialization of Irish ethnic recordings helped to spur simultaneous musical revivals in Irish communities on both sides of the Atlantic. Irish musicians in the United States had the potential to make an impact on the tradition precisely because supply and demand were strongly in their favor. Inspired by the Gaelic League, Ireland was searching for authenticity and forgotten pre-Famine Gaelic culture, and the U.S. Irish musicians were reveling in a “Golden Age” of both Irish dance and recording technology. Most importantly, the Irish musicians in the United States were virtually the only ones recording. As fiddler James Kelly has said, “The early recordings were coming into Ireland from the States and the musicians who were making those recordings were becoming influential because they were making recordings—no one had made them before.”24

Accounts of musicians in Ireland encountering recordings of traditional Irish musicians from the United States abound. In an interview with Harry Bradshaw, Tommy Gilmartin recounted that the 78 rpm recordings of flute player John McKenna

made a tremendous impact when they filtered back home. Around his native area, no matter what the cost, if you were to sell the last cow, you’d buy one of his records at the time. If you were to be without a meal a day, you’d have got the record in preference to anything else. And then there might be a local gramophone about—and maybe not very many at the time either. That house would be full to capacity that night because John McKenna’s record had arrived new that day. And there would be no work done that day in the area till it be heard, or there would get no contentment in it till it would be heard. That was the atmosphere that existed, that’s what went on.25

James Kelly has also described the excitement generated when a new recording would arrive in rural Ireland:

A family in the locality might have an old gramophone player, and when some of the 78 records would come from the States, it was like going to Disneyland! People would get together at whoever’s house it would be and they’d listen to this record over and over and over again. It was a great time for excitement, you know. So that was going on when the early recordings were coming into Ireland from the States.26

Some recordings proved to be most notable, particularly in the regions from which the recorded musician had originated. An early Columbia recording credited as Irish Bagpipes, Violin and Piano

hit the jackpot and captured the hearts of a whole generation. Black Rogue/Saddle the Pony and Londonderry Hornpipe, credited anonymously as Trio: Irish Bagpipes, Violin and Piano, is said, rather wildly, to have been in every country cottage in Ireland, and it is also said that so many people asked at the record shops, the company was forced to reverse its normal policy and name the artists: Ennis, Morrison and Muller. It soon got around that this was Jimmy Morrison, the schoolteacher from County Sligo, who had left for America only a short time before.27

Fiddler John Vesey, in an interview with Mick Moloney, mentioned that he learned a sizeable portion of his early repertoire and style from early Irish American records. As a child in 1936 he was learning fiddle from Michael Gorman, but he supplemented his studies with Irish American records purchased on trips to Tubercurry to sell turf with his father. He mentioned that on each of these trips he would be allowed to buy a record to play on the family’s wind-up gramophone and managed to find records by Coleman, Killoran, James Morrison, and Paddy Sweeney.28

Impact

As stated in many publications on Irish music, these early records had a major impact on Irish traditional music in both the United States and Ireland. The artists with the greatest reach—Coleman, Killoran, Morrison, McKenna, Ennis, and Touhey—may have had such influence precisely because they were the first to record, and their records were among the first to arrive in Ireland. Even though these records came over solely by individual agency in the early years, they became quite prevalent in Ireland, even in the rural areas. Reg Hall remembers that

I was told by one musician who would have been 80+now that Ennis Morrison and Muller’s Saddle the Pony/Black Rogue and Liverpool Hornpipe on Regal reissued from American Columbia was in every cottage around his home in Co. Offaly, which is, of course, a gross exaggeration as few people had gramophones. However, it was issued here anonymously as “Irish Pipes, Violin & Piano,” though later pressings gave the artists’ names.29

One of the areas in which these recordings had the greatest impact was on regional style. Seamus Connolly, renowned fiddle player and Sullivan Artist in Residence at Boston College, mentioned in an interview with Mick Moloney in 2004 that he first heard of Michael Coleman from his father, a bargeman on the river Shannon. He mentioned that his father brought him a recording of Coleman when he was ten, and the impact of his “lonesome” sound drove him to tears and profoundly influenced his playing style.30

Harry Bradshaw has written about the records made by Michael Coleman, mentioning in particular the effect they had on performance practice:

Coleman’s records are now regarded as classics of their kind and are among the finest examples of recorded folk music in the early twentieth Century. His style and repertoire were learnt and reproduced credibly by better players. Listened to all over the country, his articulation, phrasing, bowing and dynamics became a “standard” style.31

Many would argue that as the predominance of recorded fiddlers were from County Sligo—a distinct Sligo style became dominant among fiddlers around the world. Even today in New York City, most native New York fiddle players still carry aspects of a Sligo style introduced in these early recordings. (This trend may also have to do with the fact that Coleman’s New York students included local legends Andy McGann and Paddy Reynolds, who taught New Yorkers Tony DeMarco and Brian Conway, who taught Patrick Mangan.) The exuberance and virtuosity in these recordings is breathtaking and can be heard today in the playing of fiddlers across the United States and around the world.

Another subtle change in Irish music that seems to have resulted from the impact of early recordings is that of orchestration. Before the advent of recording, dance music had been played in unison on melody instruments. With the spatial, tonal, and harmonic constraints of the pre-electric Edison and Victor recording horns, most Irish music cylinders featured either a small grouping of one to three players, or full dance orchestras. Vocal music was usually limited to high tenor voices with brass and piano accompaniment, as these sonorities were captured best by the recording horn in the days before microphones. Studios would often ask accompanists to sit in on Irish recording sessions (often with disastrous results), resulting in many recordings with piano or even brass instruments. Groups such as Dan Sullivan’s Shamrock Band, the Flanagan Brothers, or The Pride of Erin Orchestra would record traditional tunes with large, multilayered orchestrations. As these recordings circulated around the United States and over to Ireland, other musicians or groups began to imitate these instruments and sonorities, resulting in increased solo performance and layered dance bands, often with chordal accompaniment. Of course, one of the major impacts on traditional music came from the format of the 78 itself. By 1915, the industry standard for 78 rpm records was a three-minute, twenty-second blank. With this strict limitation on the duration of music, the Irish musicians had to tailor their music to the media. The repertoire was customarily played with a tune having two repeated sections (AABB), reiterated a number of times for dancers. Unlike the two-minute single-tune wax cylinders of previous decades, other tunes were added in the recording studio while recording 78s to make a medley set. Played at a good clip, a set of tunes could be performed in just about three minutes—perfect for the 78 rpm record. Harry Bradshaw, writing on the impact of Michael Coleman’s recordings, has described the lasting impact of aspects of these influential recordings—especially the strict time format:

Through his prowess he exercised direction on repertoire too; the effects of this can be heard today in that some of his particular combinations in tune sets are still being played. Indeed, his . . . medium of the 78 rpm record itself has determined the duration of sets of tunes to this day: players still stick to the three-tune “track” which would fill one “side” on a standard 78.32

The three-tune set presentation is still strongly present in informal music sessions across the United States and is a direct reflection of the standard set by these 78s. Mick Moloney noted this trend when interviewing musicians in Chicago, finding that many of the tunes in the area had been learned from these early recordings:

The influence of the recordings in America can be illustrated by an afternoon of music I recorded in Chicago in 1977, by fiddler Johnny McGreevy and uilleann piper Joe Shannon. At the end of the session I asked both men where they learned the tunes they had been playing. No fewer than 75 percent of the tunes, it turned out, had been learned from 78 rpm recordings. In addition, their playing style was very closely modeled on that of the musicians whose recordings they had listened to. Joe, who was born in Ireland and came to Chicago at the age of nineteen, learned to play by listening to the Victor releases of Patsy Touhey. He would shut himself in a room alone for hours trying to figure out exactly what Touhey was doing on the pipes.33

Conclusion

The commonly repeated phrase “These early 78 rpm records made their way to Ireland and had a profound effect upon the tradition” simplifies a very intricate musical exchange route during a formative time in Irish traditional music, and an ongoing sophisticated conception of the larger tradition. These early systems of commercial and subcommercial musical exchange and the dialogues surrounding these exchanges seem to be the start of the system we still see in operation today in the Irish diaspora.

As the recordings bridged gaps between far-flung musicians and communities, the tradition was influenced in the realms of repertoire, individual style, regional playing style, and performance practice. The limitations of the media instituted a shift in arrangement and accompaniment, and the tangible recording morphed the function of the music from simply driving cospatial dance events to temporal and exchangeable cultural commodities. The lasting impact of these early recordings is that they facilitated a reconceptualization of Irish traditional music as a cross- Atlantic phenomenon, allowing agents from the periphery to engage actively with the core of the tradition.

References

Bradshaw, Harry. “Michael Coleman.” In The Companion to Traditional Irish Music, ed. Fintan Vallely, 75. Cork: Cork University Press, 1999.

Bradshaw, Harry, and Jackie Small. “Leitrim’s Master of the Concert Flute.” Musical Traditions Magazine 7 (1987): 9–14.

Conlon, Peter J. “The Wind That Shakes the Barley” and “The Humors of the Whiskey.” Columbia E3896. Recorded November 1917.

Engle, Tony, and Reg Hall. Liner notes to James Morrison and Tom Ennis. Topic Records 127390, 1980.

Ennis, Tom. “Murphy’s Hornpipe, Londonderry Clog, MacNamara Hornpipe.” Victor 18366. Recorded 17 April 1917.

Ennis, Tom. “Three Little Drummers, Connaughtman’s Rambles, The Joy of My Life, Nancy Hynes, Kerrigan’s Jig.” Victor 18286. Recorded 17 April 1917.

Gedutis, Susan. See You at the Hall: Boston’s Golden Era of Irish Music and Dance. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004.

Greene, Victor. A Passion for Polka: Old-Time Ethnic Music in America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Gronow, Pekka. “The Record Industry: The Growth of a Mass Medium.” Popular Music 3 (1983): 53–75.

Hernborn, Edward, and James Wheeler. “The Maid Behind the Bar-Reel” and “The Rambler’s Jig” Columbia A2147.Recorded 15 September 1916.

The Irish World, 18 May 1901.

Mitchell, Pat, and Jackie Small. The Piping of Patsy Touhey. Dublin: Na P´ıobair´ı Uilleann, 1986.

Moloney, Mick. “Irish Ethnic Recordings and the Irish-American Imagination.”

In Ethnic Recordings in America: A Neglected Heritage, ed. Richard Spottswood, 85–102.Washington, D.C.: American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, 1982.

Moloney, Mick. “Irish Music in America: Continuity and Change.” Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1992.

N´ı Fuarth´ain, M´eabh. “O’Byrne DeWitt and Copley Records: A Window on Irish Music Recording in the U.S.A., 1900 to 1965.” M.A. thesis, University College Cork, National University of Ireland, 1993.

Payer, Hollis. “Irish Fiddler James Kelly: A Matter of Tradition.” Fiddler Magazine 4/4 (Winter 1997/1998): 21–29.

Spencer, Scott. “Early Irish-American Recordings and Atlantic Musical Migrations.” In The Irish in the Atlantic World, ed. David Gleeson, 53–75. Charleston: University of South Carolina Press, 2010.

Spottswood, Richard, and Philippe Varlet. Liner notes to From Galway to Dublin: Early Recordings of Traditional Irish Music. Rounder Records 1087, 1993. Talking Machine World (1926).

Trew, Johanne. “Treasures from the Attic: Viva Voce Records.” Journal of American Folklore 113/449 (Summer 2000): 305–14.

1 For a detailed look into the means by which these recordings migrated, see Scott Spencer, “Early Irish-American Recordings and Atlantic Musical Migrations,” in The Irish in the Atlantic World, ed. David Gleeson (Charleston: University of South Carolina Press, 2010), 53–75. 2 Pat Mitchell and Jackie Small, The Piping of Patsy Touhey (Dublin: Na P´ıobair´ı Uilleann, 1986), 3 The Irish World, 18 May 1901, 8. 4 Mitchell and Small, Patsy Touhey, 10. Republished in An P´ıobaire 16/17 (1974), 5–6. The name of the recipient of the letter is taken from Mitchell and Small, as it is not noted in An P´ıobaire. The letter is not dated in either publication, but can be cross-referenced to late 1911 or early 1912. 5 Pekka Gronow, “The Record Industry: The Growth of a Mass Medium,” Popular Music 3 (1983): 54–55. 6 Early trade publications by Columbia and Victor also detail lucrative targeted recordings of Eastern European, Chinese, and Egyptian music. Recordings of African American musical forms and jazz records followed. 7 Victor Greene, A Passion for Polka: Old-Time Ethnic Music in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 73. 8 Talking Machine World (1926), 7–8. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. 9 Ibid., 96. 10 M´eabhN´ı Fuarth´ain, “O’ByrneDeWitt and Copley Records: AWindow on IrishMusic Recording in the U.S.A., 1900 to 1965” (M.A. thesis, University College Cork, National University of Ireland, 1993), 56; personal communication with Harry Bradshaw, 2 September 2007. (Ellen O Byrne used the Irish spelling without an apostrophe, cited with an apostrophe throughout Ni Fuarth´ain’s thesis. Ellen’s son, Justus O’Byrne DeWitt, embraced the Americanized version with the apostrophe.) 11 Mick Moloney, “Irish Ethnic Recordings and the Irish-American Imagination,” in Ethnic Recordings in America: A Neglected Heritage, ed. Richard Spottswood (Washington, D.C.: American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, 1982), 522. 12 Spencer, “Early Irish-American Recordings,” 55–56. This quotation comes from an interview with Justus O’Byrne DeWitt, taped by Mick Moloney, 4 April 1977, Mick Moloney Archives of Irish Music and Popular Culture, Bobst Library, New York University. See also N´ı Fuarth´ain, “O’Byrne DeWitt,” 57–58, and Greene, A Passion for Polka. 13 N´ı Fuarth´ain, “O’Byrne DeWitt,” 58; personal communication with Harry Bradshaw, 2 September 2007.Herbarn and Wheeler, Columbia A2147. 14 Ennis, Victor 18286, Victor 18366; Conlon, Columbia 3896. 15 Richard Spottswood and Philippe Varlet, liner notes to From Galway to Dublin: Early Recordings of Traditional Irish Music, Rounder Records 1087, 1986. 16 Personal communication with Philippe Varlet, 28 February 2008. 17 N´ı Fuarth´ain, “O’Byrne DeWitt,” 56. 18 Mitchell and Small, Patsy Touhey, 10. 19 Johanne Trew, “Treasures from the Attic: Viva Voce Records,” Journal of American Folklore 113/449 (Summer 2000): 305. 20 Ibid., 306. 21 Gronow, “Record Industry,” 59. The first figure is quoted by Gronowfrom Tim Brooks, “Review of Murrells’ The Book of Golden Discs,” Antique Phonograph Monthly 5/2 (1977): 8–13. 22 Ibid. Quoted by Gronow, originally appearing in the U.S. Bureau of Census 1975, 696. 23 Susan Gedutis, See You at the Hall: Boston’s Golden Era of Irish Music and Dance (Boston: 24 Hollis Payer, “Irish Fiddler James Kelly: A Matter of Tradition,” Fiddler Magazine 4/4 (Winter 1997/1998): 26. 25 Harry Bradshaw and Jackie Small, “Leitrim’s Master of the Concert Flute,” Musical Traditions Magazine 7 (1987): 11. 26 Payer, “James Kelly.” 27 Tony Engle and Reg Hall, liner notes to James Morrison and Tom Ennis, Topic Records 127390, 1980. Thanks to Philippe Varlet for the correct label information: Columbia Records, 1923. Personal communication with Philippe Varlet, 28 February 2008. 28 Recorded interview of John Vesey, interviewed by Mick Moloney, 8 January 1977. 29 Personal correspondence with Reg Hall, 20 December 2006. 30 Recorded interview of Seamus Connolly, interviewed by Mick Moloney, 7 December 2004, Mick Moloney Archives of Irish Music and Popular Culture, Bobst Library, New York University. 31 Harry Bradshaw, “Michael Coleman,” in The Companion to Traditional Irish Music, ed. Fintan Vallely, (Cork: Cork University Press, 1999), 75. 32 Ibid. 33 Moloney, “Irish Music in America,” Ph.D. diss., university of Pennsylvania, 1992, 92.