WEAVING THROUGH THE NIGHT BEFORE CHRISTMAS

WeavING THROUGH The Night Before Christmas:

The Weavers at Carnegie Hall—December 24, 1955

12/20/2015

‘Twas the night before Christmas, December 24, 1955: sixty years ago to the day this coming Christmas Eve. The Weavers, America’s consummate folk quartet, had been blacklisted since their chart-busting Number 1 hit Goodnight Irene in August of 1950—when Red Channels fingered them as a communist threat to the country and put them out of business—and two years’ worth of bookings were cancelled overnight.

‘Twas the night before Christmas, December 24, 1955: sixty years ago to the day this coming Christmas Eve. The Weavers, America’s consummate folk quartet, had been blacklisted since their chart-busting Number 1 hit Goodnight Irene in August of 1950—when Red Channels fingered them as a communist threat to the country and put them out of business—and two years’ worth of bookings were cancelled overnight.

Their leader, America’s tuning fork Pete Seeger had five kids to support, so he went out on the road and took the only bookings he could get—at schools and summer camps—below the radar screen of the FBI and Red Channels. “How much of a danger can he be if he’s just singing for children?” they surmised, and let it go. Folk music disappeared into the rabbit hole of America’s grassroots progressive underclass, out of the tony nightclubs and concert halls of Greenwich Village—like the Village Vanguard—where the Weavers got their start in 1949—the Phoenix that rose from the ashes of the Almanac Singers.

Then on August 18, 1955, HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee” finally got around to subpoenaing Pete Seeger and created one of the great confrontations in their dismal record. Pete—unlike virtually every other dissident unfriendly witness (including my own father) who appeared before them and “took the 5th”—the protection against self-incrimination—stood on the 1st Amendment guaranteeing Freedom of Speech. The questions they wanted to ask him pertained to his political beliefs, personal associations, kind of songs he sang and for whom he sang them. “The 5th Amendment,” Pete declared, “said the House Committee on Un-American Activities had no right to ask him such questions; the 1st Amendment said they had no right to ask any American such questions—especially under duress.”

HUAC cited Pete for Contempt of Congress and thus began a six-year legal odyssey of resistance to their proposed prison sentence for one of the 20th Century’s greatest artists that culminated in the US Supreme Court’s 1961 decision that found in his favor—the 1st Amendment did indeed mean just what it said—that all Americans had the right to speak (or in this case, sing) their minds. “The right to speak my mind out,” Abel Meeropol had written back in 1948—the same year George Orwell wrote 1984 about an omnipotent totalitarian regime (he meant the Soviet Union, but there were eerie parallels right here at home) where no such rights existed—“that’s America to me.” Pete’s friend Paul Robeson sang that line with his entire being, and it reflected Pete’s beliefs to the core. Frank Sinatra—whose Centennial we celebrate this December 12—also sang it—in the short Oscar-winning film based on the song, The House I Live In.

But it took a long-neck banjo-playing Adams apple bobbing hand-built log cabin dwelling folk singer from Beacon, New York, to put it in scripture—the Supreme Court’s 1961 official upholding of Pete Seeger’s rights to his personal beliefs as an American citizen. That’s when the Sixties began for me.

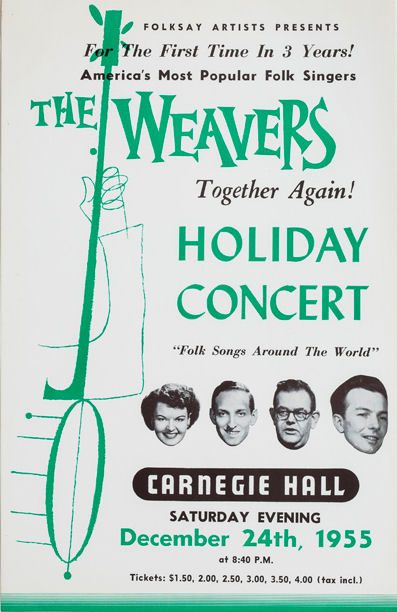

Backtrack now to that foggy Christmas Eve of 1955; The Weavers manager Harold Leventhal went on a wild goose chase and decided to book his out-of-work forced-into-retirement blacklisted quartet—Pete Seeger and co-founder Lee Hays (“Arkansas hard luck Lee Hays”), alto Ronnie Gilbert and guitarist Fred Hellerman—into New York’s most famous concert hall on the most unforgiving night of the year—when most people stayed home with their families—December 24, Christmas Eve. They hadn’t been in the public eye in three years. There was only one way it could succeed—resoundingly, or not at all.

Tickets ranged from $1.50 to $4.00. It sold out on the first day tickets went on sale—months before the concert. New York’s long-denied folk fans, that put The Weavers on the charts five years before, left their fireplaces and living rooms and came out to support their favorite folk singers and pack this classical music venue for the first time to hear down-scale rough-and-tumble songs straight out of America’s urban and rural heartland—songs like 16 Tons from the Kentucky coal mines of composer Merle Travis’s father and grandfather, Pay Me My Money Down from the Mississippi levee and dock workers, the Sloop John “B” from the Nassau sailors—and straight out of Carl Sandburg’s American Songbag—and of course Goodnight Irene, Louisiana-born Lead Belly’s theme song that had put them and folk music on the map of popular song.

During the height of the Cold War the concert struck a countercultural note of Peace On Earth and Good Will Towards Men—not the just the stock phrase from a Hallmark Christmas card, but built into the structure of the music itself—with Pete playing his banjo-driven “Around the World” medley of folk tunes from the Southern Appalachian Mountains where he first learned them from original sources like Pete Steele and Doc Boggs to the Israeli hora Artsa Alenu to Hey Lili Lili Lo from the West Indies. It was a tour de force with a message: music can bring disparate people together. It became the driving force summed up in his famous slogan neatly printed on the top of his banjo head: “This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces It to Surrender.” It was both a nod to and a pointed separation from Woody’s guitar’s slogan: “This Machine Kills Fascists.” Pete believed in the power of folk music to change the world without resorting to violence.

During the height of the Cold War the concert struck a countercultural note of Peace On Earth and Good Will Towards Men—not the just the stock phrase from a Hallmark Christmas card, but built into the structure of the music itself—with Pete playing his banjo-driven “Around the World” medley of folk tunes from the Southern Appalachian Mountains where he first learned them from original sources like Pete Steele and Doc Boggs to the Israeli hora Artsa Alenu to Hey Lili Lili Lo from the West Indies. It was a tour de force with a message: music can bring disparate people together. It became the driving force summed up in his famous slogan neatly printed on the top of his banjo head: “This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces It to Surrender.” It was both a nod to and a pointed separation from Woody’s guitar’s slogan: “This Machine Kills Fascists.” Pete believed in the power of folk music to change the world without resorting to violence.

From the first raise-the-roof major key notes of Pete’s banjo ringing:

Wake up! Wake up! Darling Cory!

What makes you sleep so sound?

The revenue officers are coming;

gonna tear your still house down

which had come a long way from the title of Pete’s very first 10-inch solo Folkways album—where he still played it in the slow modal tuning he had learned it—to the last the Weavers brought Carnegie Hall to the edge of their seats.

Nowhere is this belief better summed up than in the Weavers* adaptation of the English carol We Wish You a Merry Christmas, with their inspired conclusion:

Once in a year

It does not seem amiss

To visit your neighbor and sing out like this:

Of friendship and love

Good neighbors abound

And Peace and Good Will

the whole year around

Pachi! Shanti! Salud! Shalom!

The words mean the same whatever your home

Why can’t we have Christmas the whole year around?

Why can’t we have Christmas the whole year around

We wish you a Merry Christmas

We wish you a Merry Christmas

We wish you a Merry Christmas

And a peaceful New Year! **

Who was at that concert? A young Mary Travers, who credited the Weavers with inspiring Peter, Paul and Mary; a young Holly Near, who credited them with inspiring her to see folk music in a larger light than she had ever imagined; without the Weavers—no Singer in the Storm. And who was influenced by it? Tom Paxton, for one, who described in his farewell concert at McCabes the amazing moment of hearing the Weavers sing his brand new song Rambling Boy at Carnegie Hall in 1963—just a few weeks after he first sang it for Pete Seeger at the Newport Folk Festival; Erik Darling (who would later replace Pete Seeger with the Weavers) and the Rooftop Singers; Alex Hassilev of The Limelighters; Ernie Lieberman (my first guitar teacher) of both the Limelighters and The Gateway Singers, and most significantly, Dave Guard of the Kingston Trio; in short, every future commercial folk group worth mentioning—including finally HARP—the acronym for the 1980s post-Weavers group made up of Holly, Arlo, Ronnie and Pete.

But not just folk trios and quartets: The Weavers made sure to include Lead Belly songs Rock Island Line (which made its way across the Atlantic to Lonnie Donegan in England and launched the skiffle craze), his field holler Sylvie, Kisses Sweeter Than Wine (Lead Belly’s music, the Weavers words) which launched the career of the second Jimmie Rodgers, and of course Goodnight, Irene. Lead Belly died December 6, 1949, just six months before the Weavers made him a household name; they were the essential link on the chain that brought him into the 1960s, and invited Bob Dylan on his first original Song To Woody to add, “Here’s to Cisco and Sonny and Lead Belly too.” And speaking of Woody Guthrie—who since 1952 had been locked away in Greystone Hospital in East Orange, New Jersey silenced by advancing symptoms of Huntington’s Chorea, they also included their hit version of his Dust Bowl classic, So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh. When Woody could no longer sing for himself, The Weavers sang for him, and carried him into the 1960s. No wonder that poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg memorialized them with the highest compliment he could have paid—evoking his poetic forebear Walt Whitman—“When I hear America singing, The Weavers are there.”

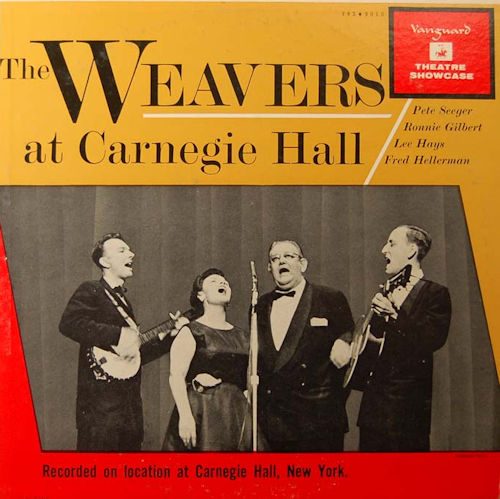

Since the concert took place at the most famous classical music venue in the country—the hallmark of great music—a small classical music record label was drawn to record it live and possibly release it. Vanguard Records founder Maynard Solomon was himself a musical visionary and recognized great music from whatever corner it came. Though their previous commercial label—Decca Records—dropped the Weavers during the blacklist and they had no label going into the concert, Maynard Solomon staked his label’s reputation and future on this unsigned quartet of blacklisted one-hit wonders. It was the big gamble that paid off beyond his wildest expectations and transformed Vanguard into the folk label of choice during the coming decade, when it became the label of Joan Baez— and Paul Robeson, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Eric Andersen, Patrick Sky, Martha Schlamme, Tom Rush, John Hammond, and Odetta—in short, the folk revival.

The Grinch may have stolen Christmas, but the Weavers gave it back to us. When Vanguard released The Weavers at Carnegie Hall—the Christmas Eve Concert of 1955—the same year Dr. Seuss’s classic was published in 1957—they took folk music out of the blacklist and into immortality.

Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!

** Footnotes:

- The Weavers used the pseudonym “Paul Campbell” for authorship and copyright purposes when adding to traditional songs, as they did here.

- We Wish You a Merry Christmas is not on the album The Weavers at Carnegie Hall, which had room for only the first half of the concert. The second half (which ends with this song) was released in 1970 as the album The Weavers on Tour. This album was reissued on CD in 1993 but is now out of print. My friend Mike Perlowin has contacted Vanguard Records with a request that it be reissued, but so far there is no news to report.

On Friday, December 25th at 7:00pm, Ross Altman celebrates The Weavers Historic Christmas Eve Concert at Carnegie Hall at the Friends Meeting House, 1440 Harvard St., Santa Monica, CA 90404, greygoosemusic@aol.com; $4 donation suggested

Los Angeles folk singer Ross Altman has a Ph.D. in English; for further information about this event Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com