Want a Little Sugar in My Bowl

Songs About Sugar Mask Centuries of Social Injustice That's Anything But Sweet

1875 sheet music depicting the sugarcane fields as a lovers’ lane. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Oh ye who at your ease

Sip the blood-sweeten’d beverage

—Robert Southey, Poems of the Slave Trade, Sonnet III

In the American South, when someone wants a hug and a kiss, they may say “Gimme some sugar.” This is particularly true among Black Southerners, and it’s a common demand from aunties, grandmothers and matriarchs who rise from that regional culture. As Fats Waller sang, confection, goodness knows, Honeysuckle Rose.

Simply put, there is no more authentically American folk idiom than the sugar blues.

The racist origins of sugar cane cultivation persisted well into the 20th century. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By 1932, when the Fleischer Studios released this cartoon, most Americans were shielded from the painful reality of what was required to sweeten a cuppajoe.

Combing through the archives, one finds songs about cutting sugar cane from Haiti, Barbados, Cuba, and Jamaica where enslaved people did the backbreaking work for centuries. Curiously, some contemporary music like the Barbados calypso by Red Plastic Bag, Sugar Made Us Free, celebrates the industry, which is critical to the economy’s rum production.

Perhaps surprisingly, the most complete collection of American folk songs about sugar are from Hawaii, where the genre is called holehole bushi, originally sung by the Japanese workers, often women, who worked the cane fields. Like the ukulele with its four strings, many of the songs have only four lines, poignant and plaintive. The songs often document the alcohol, gambling and prostitution that naturally arose as the shadow-side of the plantation system.

In 2016, Hawaii closed its last sugar mill, with Brazil emerging as the world’s leading producer of sugar today. However, the memory of the development of sugar as the commercial enterprise which overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy, leading to the annexation of the islands by the United States as a territory in1898, remains as a scar upon the culture’s psyche.

When we sing those “sugar blues,” we’re doing what Dr. Henry Louis Gates. Jr. defines as “signifying,” singing a duality where a hidden narrative lurks beneath literal meaning. Sugar-blues, sweetness and its accompanying sorrow, hold a unique place in American culture, a place often masked by faux patriotism.

Artist Kara Walker with her enormous Sugar Mama. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“Sugar” and “honey” used as endearments rankle some with Karenistic tendencies. These thin-skinned individuals protest that the likening of a person to confection is infantilizing. Well, that’s because it is.

It is no coincidence that Hansel and Gretel were lured into captivity in the witch’s hut because her home was an edible German-style gingerbread house, its spicy-fragrant cookie-walls held in place with marzipan, supporting beams of licorice, crystalized windows of spun sugar, and a roof studded with peppermints.

A similar story with strong resonance in America is the well-documented ruse used by slavers to lure African children into the holds of the ships waiting to take them across the Atlantic: the promise of a fritter tree and a syrup tree. Charlie Smith, a Black man who was taken as a child from Liberia and sold as a slave at age 12 in New Orleans in 1859, recounted this common occurrence to The New York Times , explaining that the promise of sweets in the new land had enticed hm into a life in bondage.

Nobel Prize in Literature-winning author Toni Morrison often used references to sugar as metaphors for America’s insidiously seductive racism. In Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye, the dark-skinned heroine Pecola obsesses over the Mary Jane candy bar with its wrapper featuring the brand’s white, blonde, blue-eyed namesake. Pecola devours the treat with shamanistic intent, believing that if she, too, had blue eyes, she would at last be loved. With irony that teeters on sarcasm, another short story by Morrison is entitled Sweetness.

And the cultural double-references spiral out from there. Our country’s first defining musical genres, helmed by the blues, arose from the deltas just as sugar cane flourished in the nearby Louisiana plantations, and other locales where enslaved people worked the cane fields to satisfy the world’s growing hunger for what colonials termed “white gold.”

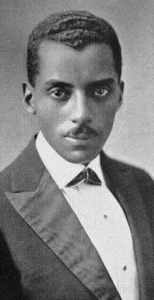

The dapper Noble Sissle, lyricist for “Shufflin’ Along” which featured his song “I’m Just Wild About Harry.” Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Consider that at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, prosperous Black New Yorkers made their posh homes in the section of Harlem known as Sugar Hill, and Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle wrote their 1921 hit, I’m Just Wild About Harry, where the speaker proclaims “He’s sweet just like chocolate candy,/ And just like honey from a bee.”

Enslaved children were frequently worked to death in the cane fields. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Honey has long been on the human menu, but granulated sugar as we know it is a more modern phenomenon.

Honey was revered as a divine sacrament across the ancient world and as the key ingredient in mead, from Mother Africa to Iron Age Wales. Perhaps resonating to ancestral memory, many blues classics allude to honey, and honeybees, swamp-griot Slim Harpo’s “King Bee” being memorably suggestive.

In these deep cuts as with many songs about sweet stuff, honey quickly morphs from a literal reference to nature’s sticky, golden candy to a synonym for a woman’s sexual favors, her money, or both. These days, country artists like Keith Anderson carry on the cross-pollinating tradition with tunes like Pickin Wildflowers.

Sugar easily moved into the same metaphoric space as cane sugar production became more commercial. In 1931, Bessie Smith recorded Lousianian composer Clarence Williams’ “dirty blues” called Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl which left little to the imagination. Nina Simone’s 1967 interpretation is smoother, less gruff, and more discreetly, exquisitely horny, complete with l’il grunts and finger-poppin’.

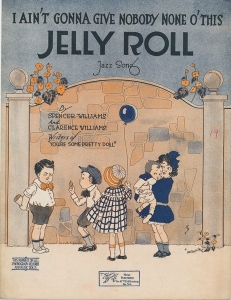

Today’s large, tattooed country artist aside, “jelly” was jazz age slang for sex, and “jellyroll” referenced his-or-her anatomy, or occasionally a coveted wad of cash. Although the sheet music may be illustrated with white children squabbling over a pastry, there’s no question that the actual narrative is about cravings and withholdings of a far more adult nature.

Sugar in the raw. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In 1914, W.C.Handy wrote his signature St. Louis Blues, where the bereft singer laments for “Blackest man in de whole St .Louis / Blacker de berry, sweeter is the juice,” saying that she “Been to de Gypsy to get my fortune ‘tole / ‘Cause I’m mos’ wile ‘bout ma Jelly Roll.”

Williams (grandfather of stone-cold detective “Linc” on The Mod Squad) penned I Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None o’ This Jelly Roll in 1919. On a literal roll with the sex-as-sweet motif, Williams went on to write Nobody In Town Can Bake a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine specifically for Bessie Smith in 1923.

Other sugary desserts from crumpets in the UK to a wedge of cherry pie in the USA took on single-entendre status as world consumption of refined sugar grew. In 1934, Tampa Red sang that his “sugar mama” had “that sweet kind of sugar make a poor man lose his mind.” Echoing similar lyrics in his My Country Sugar Mama, Howlin’ Wolf wonders “Where in the world did you get your sugar from?” Bluesmen peers like Sonny Boy Williamson added further riffs and licks, begging his granulated lady to come on home. Reversing the dynamics with tart and wily ease, in 1975 Bonnie Raitt conquered the metaphor in modern feminist terms in her stinging rendition of Glen Clark’s Sugar Mama.

Perhaps history’s most formidable Sugar Mama was the monumental 2014 sphinx-Aunt Jemima-kerchiefed sculpture by Kara Walker called “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby.” In times past, a sugar “subtlety” was a figurine crafted from marzipan or sugar paste, generally portraying a figure of power: a ruler, leader, noble, or member of the clergy. The historic concept of devouring a coveted, costly symbol of social power inspired Walker, whose interpretation measured approximately 35 feet high, 26 feet wide and 75 feet long. She defined the cane harvest as “blood sugar,” akin to “blood diamonds.”

Walker created this enormous work fabricated from water, sugar and corn syrup, installed in Williamsburg, Brooklyn’s Domino brand sugar refining plant which was demolished shortly after Walker’s exhibit closed. Walker described the1882 brick building, one of several sugar factories once located on the East River in north Brooklyn, as “weeping molasses.” As part of the exhibit, Walker also created 15 five-foot-tall, African-featured “sugar boys” made of molasses-colored candy, portraying what it took to extract “whiteness” from sugar cane. In the enormous space Walker called a “cathedral to sugar,” these small statues melted, leaving sticky, viscous, deep-red puddles of what looked like blood.

Kara Walker “sugar boy” crafted from molasses. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Papua New Guinea is identified as the likely source of Saccharum robustum, a type of giant grass, where it was domesticated in dense stands along the island’s many rivers about 10,000 years ago. Several thousand years later, elite Indian and Persian households grew sugarcane as a garden treat for special confections.

Arab traders of precious goods brought cane into the Mediterranean and on to Europe, where a massive sweet-tooth presented itself as an equally massive revenue opportunity. Although we may think of King Cotton as the engine that drove slavery as an industry, sugar was in fact the first plantation crop. The processing of sugar not only represented cake and candy, but also molasses and highly profitable rum. English, Portuguese, French and Dutch colonials eyed their various spoils from the Canary Islands to Brazil and the Caribbean as potential sugar plantations, initially enlisting (um, make that enslaving) indigenous locals to do the backbreaking dirty work.

Vintage sheet music about the tempting jellyroll. Photo: Wikimedia CommonsPapua

This strategy failed miserably everywhere it was attempted, because locals who knew their home terrain could easily escape, and also were highly susceptible to western diseases. Sensing the enormity of the financial potential, all eyes soon turned to Africa as the source of seemingly limitless unpaid labor, laying the foundation for the notorious Triangle Trade.

By the 1700s, the establishment of sugar mills in the New World made sugar accessible to the poorest residents of Europe and America. The demand for sugar was not fed simply by an idle sucrose jones. Economic factors fanned the sugar flame, starting with the fact that by the 1850s women were increasingly employed in factories to meet the needs of the Industrial Revolutions on both sides of the Atlantic. This shift led to a need for quick-energy convenience foods, including sugary cereals and jam, which were commercially produced for the first time. Sweetened tea became the mainstay even for working men, as recounted in the Irish work-song Drill Ye Tarriers, Drill, where the men “work all day for the sugar in your tay.”

The final irony of the sugar blues , November being Diabetes Awareness Month just as many of us move from leftover Halloween candy binges to full-blown sucrose-glucose-fructose frenzies triggered by December holidays, is that the sweet-seeming payload of sucrose and its relatives is a clear health hazard. This fact was suppressed by Big Sugar more than a half-century ago, and today we continue to pay the price in terms of tooth decay, and rampant obesity and diabetes.

Like an unfaithful lover we just can’t part with, much less forget, sugar is not our friend. Although the Rolling Stones gallantly banished their monster hit Brown Sugar from the tour playlist in 2016, we continue to ask ourselves, “How come you taste so good?” And we still can’t get enough.

#

Want a Little Sugar in My Bowl

Songs About Sugar Mask Centuries of Social Injustice That's Anything But Sweet