Songs of Slavery, Survival & Freedom

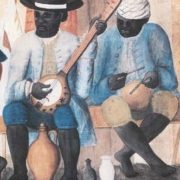

When spoken words are impossible or inadequate vessels, singing is a superpower, resonating through the body, shifting the atmosphere, and communicating beyond the words. This superpower was critical to Africans enslaved in the United States. They found solace and strength in African song as well as songs birthed from the trauma of chattel slavery. Through forceful removal from Africa, the dangerous middle passage, to inhumane treatment on the plantation, song served important purposes including recreation, prayer and worship, and work songs or field hollers. Beyond the musical aspects, singing provided religious and social commentary. All were cultural repositories connecting people from various African tribes. As Folklorist, Ralph Metcalfe observed, music is and was one of the most stable aspects of West African culture because of a reasonably cohesive musical system and the function of music at the core of African society. For Frederick Douglass, the deep, soul-stirring singing he grew up hearing “was a testimony against slavery and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains….. To those songs I trace my first glimmering conceptions of the dehumanizing character of slavery.”

From National Park Service: The Superpower of Singing: Music and the Struggle Against Slavery

Singing As Communication

- Looking for kin and countrymen

- Call and response

- Sorrowful tone

Music and the Underground Railroad: Talking Drum

Music and the Underground Railroad: the Hand Drum

Music As Expression

- Songs of sorrow, joy, inspiration, hope

- Passed through generations

- African tradition

- Known as spirituals

- Rhythms for work

- Values & solidarity

- Celebrations

- Memory tools

Songs As Strategy

- Coded songs

Supporters of the Underground Railroad used words railroad conductors employed everyday to create their own code as secret language in order to help slaves escape. Railroad language was chosen because the railroad was an emerging form of transportation and its communication language was not widespread. Code words would be used in letters to “agents” so that if they were intercepted they could not be caught. Underground Railroad code was also used in songs sung by slaves to communicate among each other without their masters being aware. - Escape directions

There were probably at least as many attempts at escape from slavery in the North America of the late 1600s and the 1700s, both individual and in groups, as in the 1800s when various forces, from the national Constitution to the local slave patrols, were all aligned to prevent escapes. While primary attention is given to the drama of slave escapes to the free states of the North and to Canada, there was also a flow of runaways into Spanish Florida and into Spanish Mexico and the subsequent Mexican Republic. Although the numbers escaping across the southern borders never threatened to destabilize slavery, there were very serious consequences for American diplomacy. Indeed, American foreign policy in the antebellum era was often driven by the need to secure the national borders and prevent slave escapes. The majority of assistance to runaways came from slaves and free blacks and the greatest responsibility for providing shelter, financial support and direction to successful runaways came from the organized efforts of northern free blacks. - Signal songs

Because many slaves knew the secret meanings of these songs, they could be used to signal many things. For example, Harriet Tubman used the song “Wade in the Water” to tell escaping slaves to get off the trail and into the water to make sure the dogs slavecatchers used couldn’t sniff out their trail. People walking through water did not leave a scent trail that dogs could follow. - Map songs

During the time of the Underground Railroad, spirituals were coded with hidden messages about maps, navigational strategies and timing for slaves to escape toward freedom in the Northern States and Canada. Some songs gave directions about when, where, and how to escape while others warned of danger along the way. Harriet Tubman, known by many as “Moses,” famously used music to communicate with travelers. Because there is no written proof of these songs or their secret codes, some scholars are skeptical of their origins. But many others accept them as part of the rich oral tradition of African American folk songs that continue to influence American music today.

Song Lyrics

A spiritual is a type of religious folksong that is most closely associated with the enslavement of African people in the American South. The songs proliferated in the last few decades of the eighteenth century leading up to the abolishment of legalized slavery in the 1860s. The African American spiritual (also called the Negro Spiritual) constitutes one of the largest and most significant forms of American folksong.

- Traditional Negro spiritual

- “Spiritual medicine”

Music was a way for slaves to express their feelings whether it was sorrow, joy, inspiration or hope. Songs were passed down from generation to generation throughout slavery.

These songs were influenced by African and religious traditions and would later form the basis for what is known as “Negro Spirituals”. Col. Thomas W. Higginson of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment recognized the term Negro Spiritual in the Atlantic Monthly (June 1867). Higginson had heard the songs in camps and on marches with colored soldiers.3

Singing at contraband camps helped former slaves navigate the gray area between slavery and freedom. Members of the contraband camp sing “There is a Balm in Gilead” as Charlotte Jenkins arrives for the first time to the Mansion House Hospital. A traditional Negro spiritual, the balm in the Gilead is interpreted as a spiritual medicine that able to heal sinners.

There is a balm in Gilead

To make the wounded whole;

There is a balm in Gilead

To heal the sin-sick soul.

Songs Of Freedom: Underground Railroad

Songs Of Freedom: Underground Railroad

- Harriet Tubman, Conductor of the Underground Railroad

- Created a network of stations and operators

- Used “Wade in the Water” as a warning.

Music was the secret language of the Underground Railroad.The path to freedom on the Underground Railroad was fraught with danger. How did fugitive slaves know which way to go? How did people communicate across hundreds of miles when to come out of hiding could mean death? Part of the answer lies in music. Songs were used in everyday life by African slaves. Singing was tradition brought from Africa by the first slaves and were used to inspire and motivate, or to express their values and solidarity with each other and during celebrations. Because it was illegal to teach slaves to read or write in most southern states, songs were also used as tools to remember and communicate.

Wade in the Water

Chorus:

Chorus:

Wade in the Water, wade in the water children.

Wade in the Water. God’s gonna trouble the water.

Who are those children all dressed in Red?

God’s gonna trouble the water.

Must be the ones that Moses led.

God’s gonna trouble the water.

Chorus

Who are those children all dressed in White?

God’s gonna trouble the water.

Must be the ones of the Israelites.

God’s gonna trouble the water.

Chorus

Who are those children all dressed in Blue?

God’s gonna trouble the water.

Must be the ones that made it through.

God’s gonna trouble the water.

Steal Away

Chorus:

Chorus:

Steal away, steal away! Steal away to Jesus?

Steal away, steal away home!

I ain’t got long to stay here!

My Lord calls me!

He calls me by the thunder!

The trumpet sound it in my soul!

I ain’t got long to stay here!

Chorus

My Lord calls me!

He calls me by the lighting!

The trumpet sound it in my soul!

I ain’t got long to stay here!

Swing Low Sweet Chariot

Chorus:

Chorus:

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home,

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home.

I looked over Jordan and what did I see

Coming for to carry me home,

A band of angels coming after me,

Coming for to carry me home.

I you get there before I do,

Coming for to carry me home,

Tell all my friends that I’m coming, too,

Coming for to carry me home

Follow The Drinking Gourd

When the Sun comes back

When the Sun comes back

And the first quail calls

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

For the old man is a-waiting for to

carry you to freedom

If you follow the Drinking Gourd.

The riverbank makes a very good road.

The dead trees will show you the way.

Left foot, peg foot, traveling on,

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

The river ends between two hills

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

There’s another river on the other side

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

When the great big river meets the little river

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

For the old man is a-waiting for to

carry you to freedom

If you follow the Drinking Gourd

UNNAMED SONG by Harriet Tubman

http://www.harriet-tubman.org/songs-of-the-underground-railroad/

Hail, oh hail, ye happy spirits,

Hail, oh hail, ye happy spirits,

Death no more shall make you fear,

Grief nor sorrow, pain nor anguish,

Shall no more distress you there.

Around Him are ten thousand angels,

Always ready to obey command;

They are always hovering round you,

Till you reach the heavenly land.

Jesus, Jesus will go with you,

He will lead you to his throne;

He who died, has gone before you,

Through the wine-press all alone.

He whose thunders shake creation,

He who bids the planets roll;

He who rides upon the tempest,

And whose scepter sways the whole.

Go Down Moses

Chorus:

Chorus:

Oh go down, Moses,

Way down into Egypt’s land,

Tell old Pharaoh, Let my people go.

Oh Pharaoh said he would go cross,

Let my people go,

And don’t get lost in the wilderness,

Let my people go.

Chorus

You may hinder me here, but you can’t up there,

Let my people go,

He sits in the Heaven and answers prayer,

Let my people go!

Goodbye Song

When that pharaoh chariot comes I’m gonna leave you

When that pharaoh chariot comes I’m gonna leave you

I’m bound for the Promised Land I’m gonna leave you

I’m sorry I’m gonna leave you Farewell, oh farewell

But I’ll meet you in the morning Farewell, oh farewell

I’ll meet you in the morning

I’m bound for the Promised Land

On the other side of Jordan

Bound for the Promised Land

I’m sorry I’m gonna leave you

Farewell, oh farewell…

Materials from this presentation may not be reproduced without the written permission of Simeon Pillich, Ph.D. Copyright © 2020 Simeon Pillich, Ph.D. All rights reserved. Please contact Dr. Pillich at pillich@oxy.edu