Song of the South: Morris Dees and Guy Carawan

The Birth of We Shall Overcome

10/08/2010

Morris Dees is co-founder with Joe Levin of The Southern Poverty Law Center, the chief tracker and prosecutor of hate crimes in the United States. They started 39 years ago and somehow have survived decades of death threats from those they have brought law suits against, including members of the Ku Klux Klan, the American Nazi Party, and Aryan Nation skinheads like California’s Tom Metzger.

Morris Dees is co-founder with Joe Levin of The Southern Poverty Law Center, the chief tracker and prosecutor of hate crimes in the United States. They started 39 years ago and somehow have survived decades of death threats from those they have brought law suits against, including members of the Ku Klux Klan, the American Nazi Party, and Aryan Nation skinheads like California’s Tom Metzger.

They typically follow criminal trials in which the criminal justice system fails to bring justice to families of murdered victims by pursuing perpetrators in civil prosecutions to put the masterminds behind these crimes-against black people, gays and lesbians, Latinos, Jews and any other targeted minority-out of business. They have literally shut down the offices of the KKK in a number of states, after all-white juries have acquitted them on criminal charges, by gaining multi-million dollar verdicts against the leaders of such hate groups and then forcing them to sell off all of their assets to pay the judgments.

But they don’t just prosecute criminals; they also teach young people influenced by them by producing documentaries and writing school curricula under the umbrella of “Teaching Tolerance,” to prevent such crimes in the future.

Every once in a while they go around the country to visit their massive network of supporters who only read about their amazing legal exploits when a trial comes to their town, and give them a “briefing,” so they will know what they have been supporting. That is what brought Morris Dees and his co-counsel in many of these cases, Richard Cohen-the SPLC President-to Royce Hall on October 5th, and why I went to see them. My late mother-God bless her-was an SPLC supporter from the very beginning, so ever since I moved in with her to take care of her when she developed Alzheimer’s, I have been reading their literature as well.

What does all this have to do with folk music? I can hear some readers wondering aloud. I wondered the same thing as I sat down in a packed Royce Hall, not knowing how I would be able to justify putting this report in our magazine. Then out of the din of several thousand people talking quietly in anticipation of what they were about to hear I heard-distantly at first, like a ship’s foghorn approaching through the fog-then more piercingly as people started to pay attention-a harmonica, playing a tune I remembered from long ago, 1963 to be precise, and then that unmistakable grainy voice singing:

Come senators and congressmen, please heed the call

don’t stand in the doorway, don’t block up the halls

for he that gets hurt will be he who has stalled

there’s a battle outside and it’s raging

it’ll soon shake your windows and rattle your walls…

For human rights attorney Morris Dees, the times, they are still a’ changing, just like Bob Dylan said they were. After that song finished I kept listening, and heard another song from a distant shore, asking some pointed questions:

How many years can a mountain exist, before it is washed to the sea

How many years can some people exist, before they’re allowed to be free

How many times can a man turn his head, pretending he just doesn’t see?

The answer, my friend, is this Southern-born civil rights lawyer from Montgomery, Alabama, whose offices, by design, overlook the 16th Street Baptist Church where four black girls were killed on September 16, 1963, in a bombing orchestrated by the local Ku Klux Klan. On the other side of their offices they are able to look out onto the Civil Rights Memorial designed by architect Maya Linn, who earlier designed the Vietnam Memorial Wall on the National Mall. On the front wall of their Civil Rights Memorial are emblazoned these words often quoted by Martin Luther King: Until Justice Rolls Down Like Waters/ and Righteousness Like a Mighty Stream.

You will also recall that this town is the birthplace of the civil rights movement, where on December 1, 1955, a black domestic worker named Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus.

Morris Dees takes this whole story, and a hundred stories it has spawned, on the road with him whenever he appears, and with Bob Dylan’s help takes you on a journey of radical rediscovery of the principles of equality on which this country was founded, and of how they can only be defended with constant vigilance and fierce dedication.

For they are under attack on every front: by armed militias, by homophobic fundamentalist Christian hate groups who picket the funerals of veterans with signs saying they deserved to be killed because they live in a country that tolerates gays and lesbians, by traditional white supremacist organizations, and by web-based groups like Storm Front who publish their hate literature under the heading of Hitler’s National Socialism-American style-and whose foreheads are tattooed with swastikas. Over 900 such groups operate all across the country, from Oregon to Massachusetts and from Montana to Louisiana, and the only reason we know their names is that Morris Dees, Richard Cohen and the Southern Poverty Law Center make it their business to watch their every move, prosecute their crimes and make their cost of doing business unaffordable.

These were the stories I expected to hear when I drove into Lot 3 at the corner of Hilgard and Sunset, to avoid the colossal traffic jam heading into the Royce Hall parking lot further west on Sunset. But I also heard a story that was pure serendipity, from the gentleman sitting next to me in the seat up the aisle about half way back from the stage. When he saw me take out my note pad to get ready for the concert-for so I regarded it-since hearing these stories of justice triumphant is music to my ears, he leaned over and asked me what I was doing. I told him I was going to be taking notes to write an essay on the evening, whereupon he murmured approvingly and further asked, “an essay for yourself?” “Well, not exactly,” I told him; “I write for FolkWorks magazine, and I plan to publish it there.” “Oh, very good,” he chimed in; “And what is FolkWorks?” “Well, it’s a folk music magazine,” I said, ” and frankly, I was a little concerned that I wouldn’t be able to justify putting this in, since it didn’t have an obvious connection with folk music. That’s why I was so happy to hear their Bob Dylan song playing.” “Oh, was that Bob Dylan?” he asked. “Yes indeed, I said, from 1963.” “That’s going to be my hook.” “Oh, very good,” he added, “Because people need to hear about this.” We kept on talking, and after he asked me where I came from I asked him the same thing: “From Everett, Washington,” he said, “maybe you haven’t heard of it.”

“Wasn’t that near where a few members of the IWW were murdered in the 1920s?” “Oh my God,” he said, “you’ve heard about that? My father worked in the mills with those Wobblies; he was a lumberman. Immigrated from Sweden.” “Just like Joe Hill,” I added. “Yes, just like Joe Hill.” And before I knew what I had opened up, I heard about his father’s hard-scrabbled life, “a disastrous life,” his son told me. His father’s name was Petrus Sellin, the Petrus deriving from St. Peter. His name was Paul Sellin, deriving from St. Paul. He told me that those immigrants gave their children the most conventional names they could think of, so as not to call too much attention to their immigrant heritage, since they themselves were all too familiar with hate crimes against immigrants of their own generation, which is what had attracted this Swedish immigrant’s son to support the Southern Poverty Law Center, who was fighting for the rights of today’s immigrants and so many others.

“Wasn’t that near where a few members of the IWW were murdered in the 1920s?” “Oh my God,” he said, “you’ve heard about that? My father worked in the mills with those Wobblies; he was a lumberman. Immigrated from Sweden.” “Just like Joe Hill,” I added. “Yes, just like Joe Hill.” And before I knew what I had opened up, I heard about his father’s hard-scrabbled life, “a disastrous life,” his son told me. His father’s name was Petrus Sellin, the Petrus deriving from St. Peter. His name was Paul Sellin, deriving from St. Paul. He told me that those immigrants gave their children the most conventional names they could think of, so as not to call too much attention to their immigrant heritage, since they themselves were all too familiar with hate crimes against immigrants of their own generation, which is what had attracted this Swedish immigrant’s son to support the Southern Poverty Law Center, who was fighting for the rights of today’s immigrants and so many others.

I asked him if he had worked in the mills himself. No, he replied, because his immigrant father was determined that his children would have a better life than he did. He did everything he could to get his children into higher education, which was their road out of the mill towns that led his son to describe his father’s life as disastrous. His father would have been proud to see that his sacrifices enabled his son to become a distinguished Professor of English at UCLA, which I only found out by doing some follow-up research after the event.

One more thing I learned from Professor Sellin before the program even started was that he was very sensitive to the fact that subsequent generations of these children of immigrants at the turn of the 20th century did not exactly remain true to their grandfather’s experience and hard-won beliefs at the hands of the oppressive wage slave system they were forced to endure, even as in many cases they struggled and risked their lives to change it. While Professor Sellin has been a lifelong activist for human rights, and by his presence was helping to support an organization that made no distinctions in their representation of members of every conceivable ethnic and religious minority, he wanted me to understand that many others who came out of his background had chosen a different path, and had acquired the same prejudices against which his own father had struggled so mightily to overcome.

That is why as soon as I mentioned the Wobblies his eyes lit up. He even mentioned that one of them-Wesley Everest-had been lynched by the same lumber trust his father worked for, in Centralia, Washington, on November 11, 1919. What a joy it was to hear these stories I had only read about in books (in this case, The Little Red Songbook) from a man who had walked down some of the same roads in these lumber camps of the great Northwest. Another member of his family had also escaped, and become a violinist in a symphony orchestra in San Francisco.

As we both settled back in our seats to listen to Morris Dees I couldn’t help but feel that I had the best seat in the house, beside a man who taught me from his own firsthand experience how many roads some people had walked down to get here, and put new meaning into Bob Dylan’s song that had been playing as a kind of overture to what we were about to hear.

Morris Dees is living proof that martyrs like Wesley Everest and Joe Hill are literally just a stone’s throw from a dedicated activist like him, who has endured more death threats than anyone I can think of. One of his more recent merchants of hate had a tattoo burned into his skinhead skull that can’t even be printed in a family magazine: “F-k the SPLC.” Thus Dees’s presence at Royce Hall required a full security detail at the door, to screen out potential threats even in Westwood.

While Richard Cohen took us through a broad survey of cases they have been working on in recent years, Dees devoted most of his seemingly extemporaneous talk to just one case-the one that put them on the map. If you thought that lynching was an antiquated practice reserved for old Wobbly heroes like Wesley Everest-who was in fact mutilated before he was lynched-and historical tales of the Ku Klux Klan, think again. It was in fact a lynching in Mobile, Alabama as recently as 1970 that compelled Morris Dees to start the Southern Poverty Law Center, the lynching of Beulah Mae Douglas’s son Michael. Just forty years ago, that strange fruit was still hanging from a southern tree, just like Billie Holiday sang about in the 1920s.

What brought Morris Dees into the case after the criminal trial had already resulted in a conviction for the 17 year-old white teenager-James “Tiger” Noles-who had been arrested for the crime was something only Dees had noticed in the autopsy photograph. It wasn’t the swollen cheeks, or the tongue hanging out of his distended mouth, or his broken neck, all of which Dees had expected to see, the very images from songwriter Abel Meeropol’s savage masterpiece:

Pastoral scene from the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth. (Strange Fruit)

What he didn’t expect to see-what it took a Sherlock Holmes to appreciate-were the boot marks on his cheeks; indicating that someone in a position of authority had held him down with his boots before the kid he had targeted with his hatred picked him up off the ground and tied a rope around his neck. Let the state be satisfied with prosecuting the witless teen who was, in the words of Bob Dylan’s song, only a pawn in their game; Morris Dees wanted the man who was wearing those boots, and who turned out to be a member of the United Klans of America-against whom Dees finally managed to secure a 7 million dollar verdict.

At the sentencing hearing for the white teenager, James “Tiger” Noles broke down and cried with remorse, and directed his plaintive words towards the murdered black boy’s mother, Beulah Mae Douglas: “Mrs. Douglas, I just want you to know that everything we did was at the direction of those Klan leaders there, and I am terribly sorry.” But he wasn’t through: “Mrs. Douglas, can you ever find it in your heart to forgive me for what I did to your son?”

It was her response that shattered Morris Dees’s composure, and made him think that there was a higher justice still than the $7 million judgment the jury awarded her: “Son, I’ve already forgiven you.” Morris Dees took that mother’s gift of mercy as a lifetime calling for him to continue seeking justice against those who peddle hate to every impressionable young mind, and try to replace that hate with a higher power-if not love, at least tolerance, to enable them “to resist the siren song of hate.”

He also wanted us to understand that hate crimes did not originate with the Ku Klux Klan or the Nazis; indeed he went all the way back to the Bible to end his talk, with a story that Martin Luther King had told time and time again about the prophet Amos, who began life as a lowly farmer at the time that Jews who were themselves the children of slaves had crossed over the river Jordan into freedom, around 900 BC. When Amos heard them complaining about their lot, and exploiting each other, he spoke up and warned them, in Morris Dees’s paraphrase of MLK, “You’ve got a good thing going here, but if you don’t stop mistreating each other and be fair one day there won’t be one stone left standing.” “When should we be satisfied?” one asked him, hoping to be let off the hook. “Don’t be satisfied,” the unwilling prophet replied, “until justice rolls down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Hard words to live by, even today, nearly three thousand years later; but Morris Dees does live by them, and with the SPLC helps keep Martin Luther King’s dream alive.

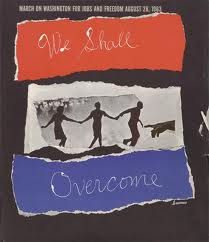

Nor are they the only ones. For there is another song of the south besides Strange Fruit, a song of hope and redemption, a song that has inspired those around the world struggling to overcome hatred and oppression-We Shall Overcome. The song came out of another organization that has been a beacon of light for over 75 years, the Highlander Folk School, which was founded in 1932 by Myles Horton and his wife Zilphia in Knoxville, Tennessee. During a tobacco workers’ strike in Charleston, South Carolina, Zilphia heard an old Georgia Sea Island hymn, I’ll Be All Right Someday, with new union words to it, to inspire members of the tobacco workers union, in the process changing the title to We Will Overcome. Pete Seeger learned it at Highlander, and would eventually teach it to Dr. King, but first he and their new Music Director, folk singer and folklorist Guy Carawan, took a closer look at it. Pete changed one word, will to shall (suggested, he later admitted, by his one year at Harvard); Guy gave it some new chords and a slower tempo, rearranging it into a church-style anthem rather than a union hall barnburner; then former Weaver Frank Hamilton added some new civil rights verses and they gave their recreated We Shall Overcome to the civil rights movement in perpetuity, by establishing the We Shall Overcome Fund, which collects and distributes all royalties from the song.

Nor are they the only ones. For there is another song of the south besides Strange Fruit, a song of hope and redemption, a song that has inspired those around the world struggling to overcome hatred and oppression-We Shall Overcome. The song came out of another organization that has been a beacon of light for over 75 years, the Highlander Folk School, which was founded in 1932 by Myles Horton and his wife Zilphia in Knoxville, Tennessee. During a tobacco workers’ strike in Charleston, South Carolina, Zilphia heard an old Georgia Sea Island hymn, I’ll Be All Right Someday, with new union words to it, to inspire members of the tobacco workers union, in the process changing the title to We Will Overcome. Pete Seeger learned it at Highlander, and would eventually teach it to Dr. King, but first he and their new Music Director, folk singer and folklorist Guy Carawan, took a closer look at it. Pete changed one word, will to shall (suggested, he later admitted, by his one year at Harvard); Guy gave it some new chords and a slower tempo, rearranging it into a church-style anthem rather than a union hall barnburner; then former Weaver Frank Hamilton added some new civil rights verses and they gave their recreated We Shall Overcome to the civil rights movement in perpetuity, by establishing the We Shall Overcome Fund, which collects and distributes all royalties from the song.

Guy Carawan, who more than anyone carried the song into the geographic heart of the civil rights movement, by teaching it to the newly formed Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, has worked in the trenches for fifty years now, since 1960, and will be coming out to Los Angeles on October 23 to let us pay tribute to his half century as a cultural worker for what is now the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee, and to raise a little money for Highlander in the process.

Producing the event is Ed Pearl, founder of LA’s premiere folk music club, The Ash Grove, and also participating will be Holman United Methodist Church’s Reverend Emeritus James Lawson, who taught Mahatma Gandhi’s method of nonviolent resistance to a young Baptist preacher in Morris Dees’s home town of Montgomery, Alabama; that would be Martin Luther King, Jr.

But the circle of cross-radiating influences, like the ripples of a pond from the tossing of a single stone, doesn’t stop there. For it was to Highlander in 1955, the year the Montgomery Bus Boycott was born, that a domestic worker named Rosa Parks came for some training in nonviolent civil disobedience. At the end of her training course, the leaders went around the circle of participants and asked each of the new graduates what they intended to do when they got back home, how they planned to put their new knowledge to use. When they came to Mrs. Parks she replied, “I don’t know what I’m going to do yet.” Her answer didn’t satisfy them and one of them said, “But Mrs. Parks, you need a plan of action; you need to have a goal; are you going to help organize your community? Are you going to register people to vote?” At this, Rosa Parks grew impatient and said, “I don’t know what I’m going to do, but I’m going to do something.”

Well, on Saturday, October 23 at 2:30pm, we in Los Angeles are going to do something to say thank you to Guy Carawan and the Highlander Research and Education Center. We are going to give a benefit concert in Santa Monica at a private home. Tickets are $35; call 310-391-5794 for reservations and address. Participating artists include Guy and Candie Carawan, Len Chandler, Ross Altman, the Get Lit Players, Betty Mae Fikes of the Freedom Singers, Bernie Pearl, and mc S. Pearl Sharp. May the circle be unbroken.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com ; see www.ashgrovemusic.com

Song of the South: Morris Dees and Guy Carawan

The Birth of We Shall Overcome