RICK TURNER, HANDMADE?:“YES, NO, MAYBE AND ALWAYS”

RICK TURNER, HANDMADE?:“YES, NO, MAYBE AND ALWAYS”

Interview with the legendary guitar luthier at NAMM 2017

2/06/2017

This year at NAMM I decided to focus on seeking out an instrument maker (luthier) that was more than a production line. With imports of instruments in mass numbers, and varying degrees of quality, I believe from a luthier’s wife perspective that it’s also important to retain handcrafted skills.

This year at NAMM I decided to focus on seeking out an instrument maker (luthier) that was more than a production line. With imports of instruments in mass numbers, and varying degrees of quality, I believe from a luthier’s wife perspective that it’s also important to retain handcrafted skills.

One such luthier is Rick Turner of Rick Turner Guitars. His remarkable story started from a small town in Massachusetts and ended up influencing the sound of many musicians / bands that are intertwined with a part of America’s musical history. He’s also a collector of Howe-Orme instruments that were coincidentally made in MA (1897-1910).

AS: What made you decide to have a booth here this year and what are your goals?

RT: Well we hadn’t done one in a couple years, we’re at a point where our production has increased, and we can increase it this year. We want to get back in the game, it was time for us to get some more dealers and here we are.

AS: You’ve been a musician, instrument repairman and luthier. How have these skills shaped your direction?

RT: When I was a very young my childhood hero’s were inventors, and then there was guitar in the house, folk music in the house, and big band music in the house. My dad was an artist, my mom was a poet; there were kindof bohemians. I got a very good early education when I went to a boarding school. Most people think oh your parents shipped you off, but no it was a great Quaker boarding school, and I was one of the folkie musicians in my class.

While in my little hometown of Marblehead, MA I found a banjo at an antique shop and it needed some work, so I took it apart, sanded the rim, refinished its varnish, and put it back together again. I guess that was my start as a Luthier; just jump in and do it. Making stuff was normal then; it was a boat-building town. I had a workshop in my basement so the transition of working on instruments was very easy, and very natural for me.

While in my little hometown of Marblehead, MA I found a banjo at an antique shop and it needed some work, so I took it apart, sanded the rim, refinished its varnish, and put it back together again. I guess that was my start as a Luthier; just jump in and do it. Making stuff was normal then; it was a boat-building town. I had a workshop in my basement so the transition of working on instruments was very easy, and very natural for me.

In 1962 I went off to Boston University for my first of two years of dropping out, and eventually dropped into a guitar repair shop in downtown Boston. That was my formal apprenticeship in what was very crude work in those days, when I think of how we leveled frets or did a neck reset, it was horrible, just horrible what we did to screw those instruments up. But by 1964, I’d gained some skills and in ‘64-‘65 I already realized the plastic bridges that Gibson was putting on their J45’s were just horrible, and said let’s get rid of this, and make a new bridge; suddenly the guitar would sound better. I also originally added the 6-½ fret to Richard Farina’s dulcimer and now apparently that’s a big deal in the dulcimer world.

In 1965 I was playing guitar a lot and got the guitar accompaniment job with Ian & Sylva (from Canada). I went on the road, recorded with them…fantastic experience, and when I was home I’d still worked on stuff. Then I moved to New York, switched to playing electric guitar, and started putting together ideas for guitars out of parts. We did an album then the band split up, and I moved to California or I moved to California and the band split up I can’t remember either way.

I was doing some session work with one of the guys that was in the Youngbloods, and then met the Grateful Dead; that was a glorious experience, it opened up phenomenal opportunities. I had started building electric instruments before I met them, and I turned out to be the right piece of the puzzle for this technical support arm of the Grateful Dead, which became Alembic.

So we wound up building their PA system, and doing their live recording, modifying instruments, building instruments for them and Santana, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, The Jefferson Airplane…the list goes on and on. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time, with the right set of skills, and brilliant co-workers.

Zap forward a few years, and I met Fleetwood Mac, spend a bit of time with them, and start designing this guitar that I thought Lindsay Buckingham would like. I left the company (Alembic), and started my own company. Lindsay got the first of the Model 1 guitars. When I took it to him in 1980, they were in rehearsal for a big tour, and his tech put the guitar up on stage. Lindsay came in picked up the guitar, didn’t put it down for 3 hours, and shouted to his guy Ray he said, leave the Les Paul, the Strat, and the Ovation at home this is all I need. And about 5 minutes later Mick came up to me and said Ok Rick this sounds great with the band, we love it…he needs a backup, NOW. Those were the first two of seven of those that he’s gotten from me. And then he’s gotten about 18 other guitars from me, and a ukulele.

Zap forward a few years, and I met Fleetwood Mac, spend a bit of time with them, and start designing this guitar that I thought Lindsay Buckingham would like. I left the company (Alembic), and started my own company. Lindsay got the first of the Model 1 guitars. When I took it to him in 1980, they were in rehearsal for a big tour, and his tech put the guitar up on stage. Lindsay came in picked up the guitar, didn’t put it down for 3 hours, and shouted to his guy Ray he said, leave the Les Paul, the Strat, and the Ovation at home this is all I need. And about 5 minutes later Mick came up to me and said Ok Rick this sounds great with the band, we love it…he needs a backup, NOW. Those were the first two of seven of those that he’s gotten from me. And then he’s gotten about 18 other guitars from me, and a ukulele.

Then in about 1981 business was bad, and I switched over the basically being a cabinetmaker /carpenter for 8 years. Then came back to work for Gibson in 1988, that ultimately became entirely too corporate, and went back out on my own with my friend David Neely doing repair work, and then one by one started building the guitars again, set up a shop, and here I am with 20 or so instruments.

AS: Are you making instrument one at a time or production scale?

RT: Yes, no, maybe and always. We have production stuff that we do, and we’re well equipped, have a very nice CNC machine for a lot of parts that we make in multiples. We do a lot of customizing for our standard instruments, so we’ll do a rosewood top on a mahogany body or maple top and just leave it mahogany; every guitar is essentially custom ordered, some of them may be more standard than others. But each one has a work order that goes with it that details every single part; tailoring to the musician or dealer whose instrument you’re putting in their hands.

AS: What changes have you see in the “Luthier world” since you started making instruments and where do you see it going from here?

RT: I think small shop luthiers had better get as high tech as they can, and hopefully they’re lucky. One thing is no matter where it was built they’ll get broken, so many luthiers shun the repair thing but that’s where there is good money, IF you’re good at it. I’m not sure I’d want to be entering the market right now as a 20 something person without going first into a lot of repair work, and I always recommend that to people coming out of Lutherie School. I think they owe it to themselves to spend 3-5 years repairing. They come out and they don’t know what goes wrong with guitars, they don’t understand why the geometry of the Martin changes to where it needs a neck reset, they have no idea how to design around these issues. And so I see a lot of them making the same old mistakes.

AS: You also have a collection Howe-Orme instruments, and mentioned getting back to some of the design elements of them.

AS: You also have a collection Howe-Orme instruments, and mentioned getting back to some of the design elements of them.

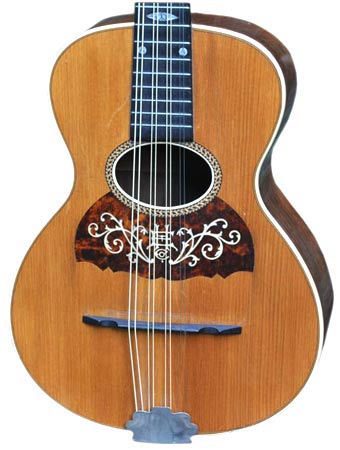

RT: Well here’s my acoustic guitar which features the tilting neck of the HO guitar, but not the arch top, but I would love to do the arch tops one of these days. I still have some HO guitars, mandolins and stuff that need a lot of work; my retirement projects. And my friend Lowell Levenger (aka Banana), between us we have most of the Howe-Ormes.

They were beautifully made and equivalent of Martin standards. There weren’t many American guitars being made that well during that time. Howe-Orme’s have this raised longitudal belly ridge that was basically heat pressed into a mandolin, octave mandolin, tenor mandola, and cello mandola. They were early in on the mandolin orchestra thing; contemporary with Orville Gibson. I think ultimately the Howe-Orme’s sound lovely but they much more a chamber instrument than the Gibson style arch top; which are more orchestral. (Ed. Note: For more info on Rick Turner and Howe-Orme Guitars, click here.

Rick Turner is currently based in Santa Cruz with and makes Renaissance Guitars. Rick co-founded Alembic, Inc. in 1969. He founded Rick Turner Guitars in 1979, and joined Gibson in 1988 where he served as president of Gibson Labs West Coast R&D Division. Leaving Gibson in 1992, he ran a guitar repair shop in Los Angeles where he developed piezo pickup designs. He later co-founded Highlander Musical Audio, manufacturer of piezo pickups for acoustic guitars.

Annette is one half of Living Tree Music & The Seagulls with her husband Nowell. She also holds a “Day” job working for the Bob Hope Estate/Family for the last 18 years. annette@livingtreemusic.com