PETE SEEGER AND THE POWER OF SONG

PETE SEEGER AND THE POWER OF SONG: TRIBUTE TO A FOLK LEGEND

A Tale of Two Tributes:

The Kennedy Center—Saturday, April 15, 2017 8:00pm

Theatricum Botanicum—Saturday, April 1, 2017 1:00pm

3/29/2017

America’s Tuning Fork, folk singer Pete Seeger, was a cultural pariah long before he was a cultural hero—but you would never know it from the most recent major tribute being planned—at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. The artist who was blacklisted for seventeen years is in the process of being both canonized and sanitized since passing away January 27 in 2014 at the age of 94.

America’s Tuning Fork, folk singer Pete Seeger, was a cultural pariah long before he was a cultural hero—but you would never know it from the most recent major tribute being planned—at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. The artist who was blacklisted for seventeen years is in the process of being both canonized and sanitized since passing away January 27 in 2014 at the age of 94.

Take, for example, this promo description of Pete’s truncated legacy by the Kennedy Center/Grammy Museum publicity department: Pete Seeger and the Power of Song: Tribute to a Folk Legend

“As a singer, folk-song collector, and songwriter, GRAMMY winner Pete Seeger spent a long career championing folk music as both a vital heritage and a catalyst for social change and remains an influential presence in the American folk music scene, even after his passing on January 27, 2014. He became a cultural hero through his outspoken commitment to the antiwar and civil rights struggles in the 1960s, and for environmental and antiwar causes in the 1970s and beyond. He wrote a number of folk standards, including “If I Had a Hammer” (with Lee Hays), “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!”–among many others.”

It sounds fine, paying tribute to Pete’s antiwar songs and participation in “the antiwar and civil rights struggles in the 1960s, and…environmental… causes in the 1970s and beyond.” But that’s not what made him a cultural hero. There were people all over the country writing antiwar songs and participating in civil rights and environmental struggles who did not become cultural heroes.

What made Pete a cultural hero—and it had nothing to do with the movements for social change in the 1960’s—was his principled stand against the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) on August 18, 1955—for which he was cited as an unfriendly witness in Contempt of Congress—initiating a prosecution with the threat of prison hanging over his head that went on for six years until 1961, when the Supreme Court of the United States found in his favor, and vindicated a singer whose career had been largely destroyed in 1950—when Red Channels blacklisted him and the Weavers—who had the number 1 song in the country at the time.

That song, by the way, was not If I Had a Hammer, or Where Have All the Flowers Gone? or Turn! Turn! Turn! It was Lead Belly’s theme song, Goodnight Irene, Life Magazine’s choice for “The Song of the Half Century,” on the basis of the Weavers recording charting the number 1 song on the hit parade for 13 straight weeks—which held the record for 25 years, against Elvis, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones. It was only the disco craze of 1975 that dislodged it. I have recounted this history in previous FolkWorks articles on both Pete and The Weavers; and don’t need to repeat myself here.

By the time Pete wrote Where Have All the Flowers Gone? in 1961, the Supreme Court had spoken, and affirmed his argument that he was within his rights when he cited the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech and assembly to refuse to answer HUACs questions and name names of his friends and political associates and activities.

Only then did the political cloud hanging over his head begin to lift. And that’s when he began to be perceived as a “cultural hero.” It wasn’t for singing—as I described it in my song “Pete Seeger’s Finest Hour,” it was rather for refusing to sing.

But don’t look for the Kennedy Center’s publicity on this “iconic folk singer, folk song collector and songwriter” for even one word mentioning this arduous, heroic and uncompromising stand against the forces of darkness which Pete demonstrated throughout the “silent fifties,” the red scare of the McCarthy era—and which had nothing to do with the antiwar or civil rights movements of a decade later. Rather it had to do with defending civil liberties and the First Amendment. It had to do with what Martin Luther King, Jr would later eloquently describe as “the right to protest for right.”

One of the most dangerous American artists of the 20th Century is about to be transformed into a noncontroversial safe embodiment of the decade of social change—which has all but been eclipsed by the recent election of the most rightwing candidate for president in our nation’s history. But the decade preceding it—the decade of the witch hunts in which one lanky New England banjo-picking folk singer who built a log cabin on the banks of the Hudson River and stood up to the United States Congress on behalf of persecuted and prosecuted minorities everywhere—that decade has not been eclipsed.

That is the decade that made Pete Seeger a cultural hero. And that is why more than sixty years later he deserves to be remembered and celebrated. Not for what he said, and not for what he sang; but for what he did not say—and refused to sing. On that day, August 18, 1955, Pete joined the ranks of dramatist Lillian Hellman, who said “I refuse to cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.” (As quoted in my song Scoundrel Time, after her memoir of the same title.) He joined the ranks of Paul Robeson, who told HUAC, “My father was a slave in this country; my father earned the right for me to live in this country, and no House Committee on Un-American Activities is going to make me leave this country;” (as quoted in my Ballad of Paul Robeson.)

And he joined the ranks of two-time Nobel Prize-winning chemist and peace activist Linus Pauling, who, like Pete, refused to cooperate with HUAC on the basis of the First Amendment—not the Fifth Amendment—which guarantees the right against self-incrimination. Pete defined the difference better than anyone else: “The 5th Amendment,” said Seeger, “says the Committee has no right to ask me such questions; the 1st Amendment says they have no right to ask any American such questions, especially under this kind of duress.” In other words, Pete stood up for us all, not just himself.

Songwriters—even great songwriters—come and go; but a great citizen stands apart, and that is why Pete remains a cultural hero. We won’t see his like again; we were lucky to see him once. “It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.”

Tickets for the Kennedy Center tribute range from $39 to $129. Their press release continues as follows: Presented in conjunction with the GRAMMY Museum in Los Angeles, Pete Seeger and the Power of Song: Tribute to a Folk Legend is a special one-night-only concert that will celebrate the artistry and lasting influence of American folk icon Pete Seeger with some of yesterday and today’s most beloved artists performing his memorable classics. The musical evening will feature GRAMMY winners Rosanne Cash, Judy Collins, and Peter Yarrow and Noel Paul Stookey (of Peter, Paul & Mary), and Tony Trischka, Josh White Jr. and (I just learned from the Grammy Museum) Tom Paxton and Roger McGuinn doing Turn! Turn! Turn! on his Rickenbacker 12.

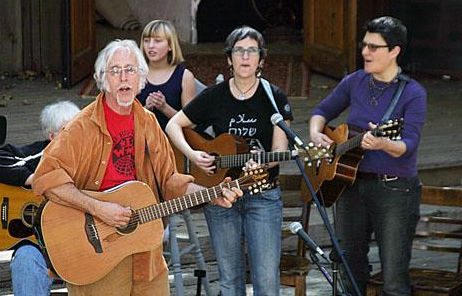

Can’t make it to the Kennedy Center? Worry not; if you are not able to attend or afford their star-studded Americana version of Pete tribute, you can simply drive to Topanga Canyon’s Theatricum Botanicum for their 3rd Annual Re-PETE on Saturday, April 1 from 1:00pm to 5:00pm. No stars, but a good, solid lineup of local artists paying tribute to the Un-Americana protest songs and indomitable spirit of Pete Seeger; including:

With The Geer Family Singers, Peter Alsop, Ellen Geer, Melora Marshall, Earnestine Phillips, Marshall McDaniel & friends, Ross Altman, Lily Andrew, Meredith Axelrod, Antonia Bath, Dave Crossland, Rick Ellis, Frank Fairfield, Brianna Falcone, The Freakniks, Katherine Griffith, The Little Miss, Carol McArthur, Claudia Lennear, Victoria Hilyard, James McVay, Eric Schwartz, Sky Wahl, Sunny War and more

PETE SEEGER-HIS SONGS & SPIRIT – “The Rising Of The Women”

At the Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum

1419 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd., Topanga, CA 90290-4275

310-455-3723

You’ll get to hear actress Ellen Geer read Lillian Hellman’s letter to HUAC that defined the conscience of an era and refused to bow to its climate of fear; and my song for Pete’s finest hour, played on my long-neck banjo. Another highlight will be Peter Alsop’s performance of Pete Seeger’s story-song Abiyoyo—not to be missed. This amphitheatre embodies Pete’s spirit, having been created by actor Will Geer—best remembered as Grandpa Walton—who was an unfriendly witness before HUAC and lived to tell the tale. Ellen Geer and Melora Marshall and Peter Alsop carry on Will and Herta Geer’s legacy.

Full disclosure: I carry on my father’s, who also refused to name names before HUAC.

Pete Seeger remains a dangerous artist—to those of us who he inspired ever since Holly Near heard the Weavers in Concert at Carnegie Hall on Christmas Eve in 1955—and realized then and there what she wanted to do with her life. Mary Travers was in the audience too—and had the same epiphany. Holly Near’s song A Singer in the Storm was born right there—even if as yet she had no words to express it. We are still singing in the storm, and have Pete to thank for giving us the words and music and determination to keep on singing—come what may.

Carry it on.

Go to the links above for information and tickets.

Ross Altman is a member of Local 47 of the Musician’s Union and has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com

The

The