Mike Seeger

old-time musician

AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW

4/29/2008

It was mid-afternoon in the modest green room of UCLA’s Schoenberg Hall, where ethnomusicology students and aficionados of Southern traditional music had gathered to chat with musician-field researcher Mike Seeger. A soft-spoken man, who often pauses thoughtfully to find the precise word to express his meaning, he had just concluded a lecture on the history of the Southern guitar. This was part of a two-week stint in the Department of Ethnomusicology where students and faculty benefited from his breadth of knowledge of rural songs and of performance styles on instruments ranging from the banjo, fiddle, and mandolin to the less familiar lap dulcimer and quills (Southern pan pipes). Today’s lecture also tied in with Seeger’s most recent Smithsonian Folkways recording, Southern Guitar Sounds, which he is following with a two-DVD instructional program due for distribution next fall.

It was mid-afternoon in the modest green room of UCLA’s Schoenberg Hall, where ethnomusicology students and aficionados of Southern traditional music had gathered to chat with musician-field researcher Mike Seeger. A soft-spoken man, who often pauses thoughtfully to find the precise word to express his meaning, he had just concluded a lecture on the history of the Southern guitar. This was part of a two-week stint in the Department of Ethnomusicology where students and faculty benefited from his breadth of knowledge of rural songs and of performance styles on instruments ranging from the banjo, fiddle, and mandolin to the less familiar lap dulcimer and quills (Southern pan pipes). Today’s lecture also tied in with Seeger’s most recent Smithsonian Folkways recording, Southern Guitar Sounds, which he is following with a two-DVD instructional program due for distribution next fall.

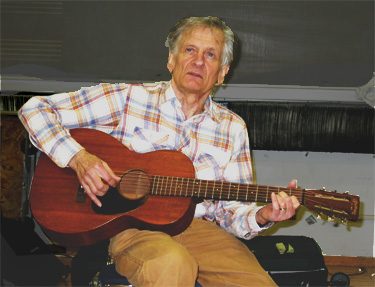

For over 40 years, Mike Seeger has passed on the legacy of his parents, composers and musicologists Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger, who inspired him along with his sister Peggy and brother Pete to champion traditional music in illustrious careers. Founding member of the vanguard old-time string band, the New Lost City Ramblers and director of numerous traditional music festivals, his looks belie his 75 years and middle-class, city roots. Erect of posture, he is slim and square-shouldered, typically wearing a cotton plaid shirt and khaki jeans. A tuft of his thick gray hair stands straight up over his high forehead, giving him a somehow “country look.”

At last the students and fans from the public had left the green room and Mike Seeger relaxed on a sofa with his wife Alexia, ready to answer a few questions on the path he has taken in traditional music.

AC: You’ve been a visiting Regent’s lecturer at UCLA, giving master classes and lecturing, but I notice that your academic background isn’t included in your bio.

MS: (chuckles) That’s because I don’t have an academic background.

AC: How does that affect your approach to music and the kind of historical exploration you do – not coming from any one academic discipline?

MS: Well, I was reared with old-time Southern music on records and by my parents advocating for that kind of music. They encouraged us to play and to be curious about it. I followed that for the past 60 years and then sometimes people like for me to come and tell about it…because along the line I’ve met a lot of traditional musicians and have some thoughts about the Southern traditional folk music.

AC: Were you friends with Alan Lomax?

MS: I knew Alan Lomax. He came to visit my folks. I served on an advisory board or two with him. And he hired me as a musician once or twice to work with him on a project. He wanted me to come and work with him on his cantometrics program, but I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to play music. He was an amazing guy. If it hadn’t been for Alan Lomax, I don’t know what I would have sung because he did so much collecting in the South. A lot of the songs I sing, he collected. Some were collected by his dad, too, who I also knew.

AC: Tell me about your relationship with Elizabeth Cotton.

MS: She worked at our house for about five years before Peggy found her playing the family guitar which embarrassed Ms. Cotten. I was just starting to play guitar myself…So we got her to play for us…When our house broke up after my mom passed away and we all dispersed, I kept in contact with (Elizabeth Cotton) because I lived nearby. And I also came to realize through my connection with Folkways, which had started about a year before that, that the time might be right for her to make a record. So I visited her several times over a period of months and recorded her in her bedroom sitting on her bed with her three great grandchildren whom she was taking care of at the time. (The record was released on Folkways (now Smithsonian Folkways.)) Shortly after that, because of the recordings, she began getting calls and I began getting calls asking her to come and play. We gave our first solo concert together, each of us doing a set. And that started both of us out to develop our stage personality. She was a superb player.

AC: Has anybody ever expressed to you, “How can a white guy with a middle class upbringing represent our music?”

MS: People do bring up the issue of authenticity, yeah. And I am different from the people I learned from, there’s no doubt about it. White and black.

AC: You didn’t grow up in the Appalachians and you didn’t grow up in the Delta.

MS: I grew up hearing the music. But my father talked New England and my mother talked old time mid-Western.

AC: Didn’t some musicians give you a hard time?

MS: Some kidding from old-time people. It was friendly kidding. They called you a Yankee or a damned Yankee. Or they make fun of my saying “lunch” instead of “dinner,” because dinner is mid-day and lunch is northern. (chuckles) And supper-that’s okay at night. There’s some differences like that. But mostly, if you’re friendly and you like how they’re talking and you like how they sing, you can be friends. And that’s the way I feel.

AC: They feel the genuine respect.

MS: I guess they do. That’s the critical thing.

AC: Do you think that traditional musicians accept you more readily because you come with an openess rather than a scholarly approach?

MS: I think they like that I talk directly to them and love the music. I think that’s what makes the difference. If I had had some scholarly training, I hope that that wouldn’t have changed that. But as it is, I didn’t. I’ve completed high school. But some people think I’m an academic person, and if academic means that you’re interested and curious, I guess maybe I am. But I’m not academically trained except informally. Quite often musicians haven’t had a lot of formal schooling, but they’ve learned things from life that we’re interested in.

AC: Do people ask you what the future of this kind of music is?

MS: That question does come up from time to time…I was hoping 48 years ago when I started playing this for a living that by playing this music it would help make a future for this music. I was one of a few dozen people who were playing music in the sixties who have played a part in the continuation and expansion of people playing old time string music to where there are now thousands of people playing it, both north and south, east and west. And I’m confident that it will continue. That there will continue to be people who like to play tunes exactly the way they used to be played and some people who will mess around with it and change things.

AC: What gives you that confidence that people will respect the traditional styles?

MS: I’ve seen the process over the past 50 years and it gives me optimism that people are going to want to make music like this music indefinitely. I meet some people in their twenties who are playing. I’ve seen their parents -or the equivalent of their parents-when they were in their twenties and who are now in their fifties saying, “I don’t know if it’s going to continue or not” and thirty or forty years later, they’re still playing…As long as they do it in public, there’ll be some young kids who want to do that. Not everybody wants to be a consumer and watch somebody else do something. People want to do something for themselves. You can do parts of it without too much trouble and you can make it as deep as you want or as difficult as you want.

AC: You’re talking about a sense of continuity. It’s so different from the world of computers and technology where this year’s computer is outmoded in six months, ready to be trashed and re-invented. So when you come across a tradition like this and you can trace it back and find yourself playing at least an approximation of what was played in the past, there’s something exciting about it.

MS: It’s true. That’s why I’m optimistic about that continuing. The thing I don’t know is whether the human race is going to continue for another hundred years. At least as long as we have fiddles and banjos and food to eat, there’s going to be music with it.

AC: Do you have a favorite instrument, the one where it all began?

MS: No, the instruments that I play are all pretty familiar to me. Sometimes when I play them, because I’m getting older, it takes me longer to get used to a certain motion, but it all feels very much at home.

AC: If you could only take one instrument with you on a ten-year trip, which one would it be?

MS: If I had one instrument, it would probably be the banjo.

AC: Tell me about your most recent recording project.

MS: The most recent is Southern Guitar Sounds and it’s a CD of 28 tracks that are mostly different styles of guitar on about 25 different instruments. That’s the one I wrote the notes for. And then I’m also putting out a two-DVD instructional set on most of those styles playing the same instruments and the same pieces, but showing up close how they’re played.

AC: And the distributor?

MS: Homespun Tapes. It will be out in the fall of 2008.

AC: Anything you want to share about future directions?

MS: (laughing) My direction will continue. I’ve really liked being part of an academic program as much as I’ve liked being part of a festival in Hinton, West Virginia or a party at somebody’s house, playing old time music. It’s all pretty amazing.

Audrey Coleman is a journalist, educator, and passionate explorer of world music and culture.

Mike Seeger

old-time musician

AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW