Gordon Lightfoot: Banned In the USA?

Live at Royce Hall, Tuesday, November 8, 2011 8:00pm

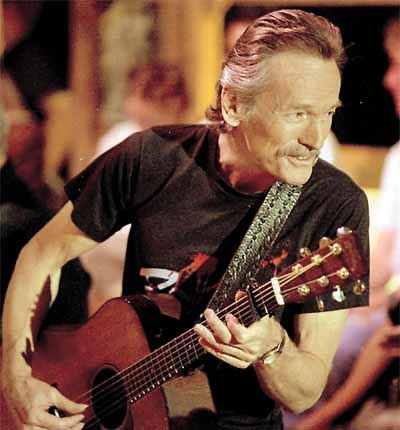

Canada’s highest civilian award—the Order of Merit—doesn’t grow on trees; it has been bestowed on only three musicians, and one of them will be at Royce Hall on Tuesday evening, November 8 at 8:00pm—Canada’s Folk Laureate, Gordon Lightfoot. He once lived in Los Angeles, way back in 1958, when he was just 20 years old. He stayed here for two years, already determined to be a singer/songwriter, when like the hero of a great French-Canadian folk song, Un Canadien Errant he got homesick. In the folk song he tells his friends, If you see my homeland, tell my friends I will always remember them.

Canada’s highest civilian award—the Order of Merit—doesn’t grow on trees; it has been bestowed on only three musicians, and one of them will be at Royce Hall on Tuesday evening, November 8 at 8:00pm—Canada’s Folk Laureate, Gordon Lightfoot. He once lived in Los Angeles, way back in 1958, when he was just 20 years old. He stayed here for two years, already determined to be a singer/songwriter, when like the hero of a great French-Canadian folk song, Un Canadien Errant he got homesick. In the folk song he tells his friends, If you see my homeland, tell my friends I will always remember them.

The line is so famous it is engraved on their license plates, in French of course: “Que Je Me Souviens D’eux.” Lightfoot went him one better, and returned home to Canada. Though he has never lived here since, his music has made a new home south of the border, where he is one of Canada’s most enduringly popular artists. He has recorded 20 albums and toured extensively for five decades. His songs are covered by artists all over the world, and include some of Canada’s and America’s own major songwriters. But that’s not why I am recommending you go see and hear him.

Rather it’s because of the following, an interview I transcribed from the CBC (Canadian Broadcast Corporation) that took place on April 13, 1968, when Gordon Lightfoot—not Phil Ochs, or Bob Dylan, or Joan Baez, or Buffalo Springfield, was banned in more than thirty states across the U.S.A. If when you think of Gordon Lightfoot you only remember Ian and Sylvia singing Early Morning Rain, or his later hit song If You Could Read My Mind, or even The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald and epic Canadian Railroad Trilogy, there is another side of him that puts him squarely in the tradition of great protest singers from Woody Guthrie to Pete Seeger.

But don’t take my word for it; Lightfoot could—and did—speak for himself:

Gordon Lightfoot Interview on CBC April 13, 1968

“Gordon, why do you think Black Day in July has been banned in the United States, in so many cities?”

“Well, it hasn’t been banned because it’s obscene, or anything like that. When I first started to do it, it was being played—a lot of stations were playing it; but top-40 stations have a policy—a lot of them don’t want to upset their listeners. ‘It’s the housewife in the morning; let’s give her something that will make her happy; why give her something that will make her think?’ They’re beaming out to teenyboppers—that’s who they’re aiming at—hoping to get the adults at the same time; ‘now what do they want to know? Why tell them something they already know and make them unhappy?’ You know these guys are trying to sell products…I know for a fact that there are two or three stations in Detroit that are playing it, because I was there about two or three weeks ago…and it is being played; it was being played in Los Angeles in the Top-40 stations; there are some Top-40 stations that will take on a number like that; what happened was that Martin Luther King got assassinated in the middle of all that and I guess it would be too much to play a record like that; I can well understand why it wouldn’t be played.”

“You think there is some feeling that it might incite further riots?”

“Possibly—if it became a major number, if people started to go out and buy it, it could have an awfully great effect and maybe not too positive.”

“What do you think?”

“I say that the thing could have helped; probably could have done some good—had it not been for the fact that Martin Luther King was assassinated right at the time that it came out.”

“You’ve sung this in concert in the States?”

“Oh sure.”

“Whereabouts?”

“I’ve sung it in Detroit; I’ve sung it in Los Angeles and Boston, you know.”

“Have you had any mail on it? What kind of comments do you get?”

“Well quite honestly, I haven’t had anyone call me up and tell me it was a stupid song, or distasteful. No one has said that; everyone has said ‘It’s a good constructive song; it’s a journalist’s-eye view of a situation that exists and that’s what it is.’”

“Did you get any comments from the officials in Detroit? The mayor’s office? The governor? The president? All of those people?”

[Gordon laughs}“No, I’m afraid we didn’t reach into any of those homes yet. It’s not really a controversial song…it just makes a statement that doesn’t have to be made at this particular time because it’s all too obvious; I guess that’s why they don’t choose to play it. To be quite honest with you, I didn’t expect they would play it, when I put it out.”

“Were you in the Detroit area last summer when all of this happened?”

“No, I wasn’t; but I’ve been there several times and worked very close to where it happened—on the west side of the John Lodge Expressway; as a matter of fact at the club where I worked everything around it was burned down—the whole block was gone—I went back there this time—not to work in a club; I was doing a concert this time, but the whole club…everything around it was gone…it was leveled out.”

“Have you spoken to any people who were there when it happened?”

“Yes, one very good friend of ours down there; Don Durany is a psychiatrist in a clinic and he told us and described it all to us; ‘When you see a tank sitting on the main street, you know, with a machine gun going…it sort of wakes you up a little bit.’” “You can read it in a newspaper and say fine—there’s a tank, but when you see it in person, you know, in the main street of an American town, an American city…they want to get a sniper out from behind a wall…in one case they just blew down the whole wall…that’s all they could do, and of course the sniper escapes. And then of course about ten miles from the riot area there’s a lot of people who don’t care at all…even then while it’s happening—they say, ‘well that’s fine you know…just keep it downtown and don’t bother me with it.’ People living within ten miles of it are so apathetic it’s just unbelievable.”

“I’ll be doing this song and carrying it through…all I try to do when I introduce the song is make people more aware; that’s what the song is for…I mean a singer of songs, a songwriter or a poet or anything—you can’t offer or give somebody the solution; all you do is—when you get in my position and you’re singing to a lot of people—you get up and try and do something constructive—about caring; that’s what the song is for. Let’s everybody care a little bit more.”

“Gordon, thanks very much for talking with us today.”

Bruce Springsteen may have been born in the U.S.A., but Gordon Lightfoot was banned, and that’s a far higher honor in my book. It’s not as if Detroit didn’t have its own recording artists, and recording studio— Motown? Hello—but it took this white Canadian, not Smokey Robinson, or Marvin Gaye, or Aretha Franklin (Sam Cooke had passed away in 1964, just a few months after recording A Change is Gonna Come) to put the mirror up to the inner city and tell it like it was.

Yes, later on Elvis would record Mac Davis’s fine song In the Ghetto (released in 1969), but that’s not a political song, rather a tragic statement of the conditions of poverty with no way out. Lightfoot’s song described a situation in which poor black people were fighting back against those conditions. And most significantly, it clearly took their side and said, in terms of understanding the motivation for the riots,

In the mansion of the governor…

They wonder how it happened

And they really know the reason

And it wasn’t just the temperature

And it wasn’t just the season.

“It wasn’t just the temperature and it wasn’t just the season:” What was it then? Lightfoot doesn’t mince words, or accept a sentimental homily to brotherhood:

And you say how did it happen

And you say how did it start

Why can’t we all be brothers

Why can’t we live in peace

But the hands of the have-nots

Keep falling out of reach.

Gordon Lightfoot kept on drilling until he got to the truth. That’s what a great songwriter does. And he carried that Truthdig aesthetic into a great antiwar song as well: The Patriot’s Dream from the album Don Quixote, which he describes in detail from many points of view (the soldier, the young son, his true love left behind, and his mother and father) all seen through the lens “of the patriotic fever and the cold steel that kills.”

Don Quixote, the medieval Spanish hero of Cervantes’ masterpiece, was not unlike this modern troubadour—tilting at windmills—in this case the windmills of war, racism and poverty. That may not be the Gordon Lightfoot of his great love songs, or his great historical ballads, which earned him the title of Canada’s Folk Laureate. But it is my Gordon Lightfoot, Canada’s social conscience for the last half century, and fortunately for us, ours as well. He blazed the trail for Ian and Sylvia, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young and later on Stan Rogers.

Don’t miss this rare opportunity to see a true pioneer, and welcome the traveler home. Think of something nice to say, just in case this old airport’s got him down, and he’s cold and drunk as he can be, before he gets back on his way, in the early morning rain. Thank him for me.

Ross Altman has a Ph.D. in English. Before becoming a full-time folk singer he taught college English and Speech. He now sings around California for libraries, unions, schools, political groups and folk festivals. You can reach Ross at Greygoosemusic@aol.com

Gordon Lightfoot: Banned In the USA?

Live at Royce Hall, Tuesday, November 8, 2011 8:00pm