ERIC ANDERSEN’S RIVER OF BLUE

FLOWS WITH A LEGACY OF SONG

Eric Andersen was there at the birth of the singer-songwriter movement of the 1960s. But, his story is not bound in time. While his contemporaries include Tim Hardin and Fred Neil, his is a distinct voice. He’s a blues enthusiast who reads the Beats; He’s a rocker who leans deep into his own poetry distinct from Dylan or Cohen. At times his music calls to mind a gentle blue river while at other times you may find yourself knee-deep in the rivers of the delta on a full moon night with screaming slide guitars calling in the distance. There is no stronger example of this than his 2007 live album, Blue Rain. If you explore the legacy of his recorded work over the last 40 years, you’ll hear him trading off lyrical licks with Lou Reed, harmonizing with The Band’s Rick Danko, co-writing with Townes Van Zandt or singing a tribute to Jack Kerouac.

Eric Andersen was there at the birth of the singer-songwriter movement of the 1960s. But, his story is not bound in time. While his contemporaries include Tim Hardin and Fred Neil, his is a distinct voice. He’s a blues enthusiast who reads the Beats; He’s a rocker who leans deep into his own poetry distinct from Dylan or Cohen. At times his music calls to mind a gentle blue river while at other times you may find yourself knee-deep in the rivers of the delta on a full moon night with screaming slide guitars calling in the distance. There is no stronger example of this than his 2007 live album, Blue Rain. If you explore the legacy of his recorded work over the last 40 years, you’ll hear him trading off lyrical licks with Lou Reed, harmonizing with The Band’s Rick Danko, co-writing with Townes Van Zandt or singing a tribute to Jack Kerouac.

There’s no doubting, Eric Andersen loves the Beat writers of the 1950s. He’s clear with his affinity for Kerouac, Ginsburg and Burroughs. He recently wrote an essay for the anniversary edition of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch (called Naked Lunch@50) and was the musical guest at release parties in Paris and New York. But if Andersen were one of the Beats, he’d be the naturalist Zen poet, philosopher, Gary Snyder. There’s something of the contemplative poet-mystic in him. His visions run in gentle waters, then shift into the dark chaos of the blues as he discusses Robert Palmer’s classic book, Deep Blue.

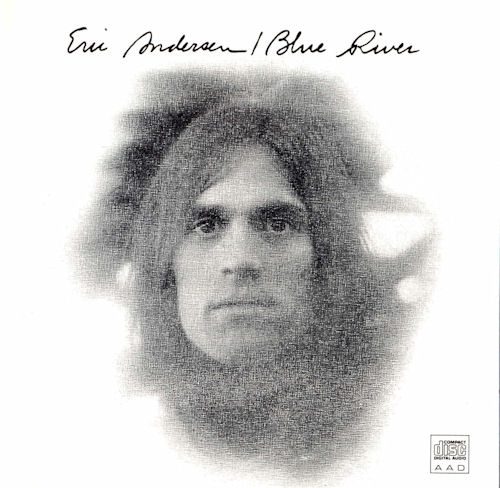

While lesser songwriters of the day pursued commercial success, Eric was the restless-gypsy kind and ran along side his own river finding himself a witness to the deeply-rooted Americana muse of Dylan and The Band’s Woodstock-Big Pink days. He chronicles this in the following interview describing the birth of his trance-like signature song, Blue River with Robbie Robertson and Rick Danko witnesses as they gazed at the Hudson River one autumn afternoon in the early 1970s. His best known songs, Violets of Dawn, Come to my Bedside and Thirsty Boots have been recorded by Judy Collins, John Denver, Rick Nelson and Mary Chapin Carpenter. Today, he is established as a mentor songwriter who has reached out to the generations that followed him. He has been an example of an artist who compels and draws us into his circle of song.

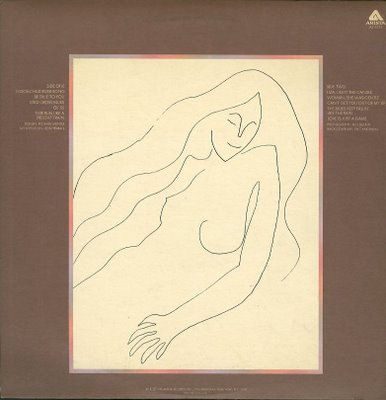

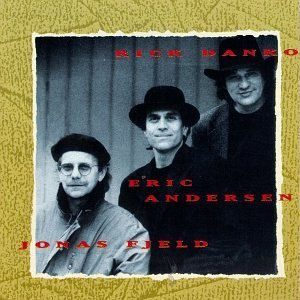

After a string of successful folk albums in the 1960s, he was poised for success with the 1972 release of the now classic Blue River album. It was met with critical and commercial success. As fate would have it, the follow-up album, Stages, would be lost by the record company not to resurrect for another 20 years. The release of this album led to a collaboration with old friends Norwegian singer-songwriter, Jonas Fjeld and Rick Danko of The Band. The trio turned in three successful albums which led to a deepened friendship between Danko and Andersen. Somewhere, folded into this collaboration is evidence of how songwriters become more than just entertainers, more even that just artists; the music of this trio on these three albums comes across like we’ve been present to the rite of passage of three true blood brothers embodied in song.

After a string of successful folk albums in the 1960s, he was poised for success with the 1972 release of the now classic Blue River album. It was met with critical and commercial success. As fate would have it, the follow-up album, Stages, would be lost by the record company not to resurrect for another 20 years. The release of this album led to a collaboration with old friends Norwegian singer-songwriter, Jonas Fjeld and Rick Danko of The Band. The trio turned in three successful albums which led to a deepened friendship between Danko and Andersen. Somewhere, folded into this collaboration is evidence of how songwriters become more than just entertainers, more even that just artists; the music of this trio on these three albums comes across like we’ve been present to the rite of passage of three true blood brothers embodied in song.

Today, Eric continues to flow along with his own blue river from his home in the Netherlands. He still writes, records and performs with nothing less than a poetic passion. This is striking during the interview. When talking about songwriting, he’s still hungry, restless for some new breakthrough in his pursuit of the song. And this is what makes him a great artist. After decades of recording, he still calls himself a seeker of the song and he invites us to join him on the exploration.

TR: I noticed quite a bit of Beat influence in your projects over the years.

EA: The Beats were different. Not the kind of literature we were learning in school at the time. It was the school of life. They spoke in a vernacular that was more interesting than what we read and heard in school.

TR: You’ve walked some diverse paths in your art and music.

EA: These are the things that keep me alive. It keeps the wood in my fire. Like Lou Reed and I did a song together, You Can’t Relive the Past. We wrote it together and then he offered to play on it.

TR: What’s going on right now?

EA: I have a new album coming out. It’s a live album from Cologne, Germany. It’s called the Cologne Concert. It’ll be out next month. I’m also working on an album of new material.

TR: I noticed your L.A. show at McCabe’s will include Van Dyke Parks.

EA: Yeah, we met at McCabe’s 50th anniversary show. He was so kind. We clicked. He’s really such a transcendental talent. Around the same time, he came to a Pasadena gig and sat in on accordion. I also heard him play in the Netherlands. He did a kind of show where he talked and played piano. He was immensely impressive, a great keyboard player.

TR: Speaking of accordion players, you played quite a bit with Rick Danko of The Band.

TR: Speaking of accordion players, you played quite a bit with Rick Danko of The Band.

EA: I met Rick in L.A. around ‘67. He invited me to Woodstock. It was autumn. It was this rock and roll suburb. We went to Robbie Robertson’s. He took me to the Hudson River on this long bridge. It’s like the story of your life. We stopped to take a look at it. I remember I saw a train go by. I went back to L.A. and wrote Blue River. Joni Mitchell heard the song, loved it. She started singing with it. She loved the title. She was working on the Blue album. She wanted me to lend her the title for the album. She liked it better than just Blue. But, I didn’t let her have it (laughs).

TR: The other song that resonates for me on the album is Wind and Fire.” It seems like an extension of Blue River.

EA: Yeah….it was all connected. We were all in the same boat.

TR: And sometimes train. Tell me about the Festival Express Canadian tour in 1970?

EA: That was a great experience. One of the greatest rock and roll parties ever. I was the only acoustic act on the show. It was good for me to be there. At one point, things were getting crazy. They put me up on a bus and I did a song with Jerry Garcia. During that set, we stopped a riot from happening. There were so many wonderful people. We checked our ego at the hat rack. It was an amazing time.

TR: I saw the film. There’s a scene with Rick singing, Ain’t No More Cane on the Brazos. Janis Joplin looked like she was going to eat him alive.

EA: (laughs) She probably did later. Those things happened out there on the road.

TR: Blue River seemed rooted in the Woodstock experience with Dylan and The Band. The follow-up, Stages, got caught up in record label problems and was lost.

EA: Yeah. When it did come out in 1991, it received great reviews. And it was reviewed as though it had just been recorded, not something from the past. Critics gave it four stars. The reviews didn’t say,’pretty good for an old album.’ It held up through time. That record proved the cream rises to the top. It still stands today.

TR: Working on it 20 years later led to your collaboration with Rick Danko and Jonas Fjeld.

EA: They came in to help with the bonus tracks. That’s how we started. We had a harmony trio. It was quite nice. We got together, did a couple of albums. I heard it was one of Dylan’s favorite albums. He got frustrated because when it was released, Tower Records didn’t have it in stock. Dylan’s always been supportive.

TR: It was quite a blow when Rick passed.

EA: I loved Rick. I miss him every day. They say, ‘when you were born the angels sang and Rick Danko was singing harmony.’ You know, you’re lucky if you can create a work of art where the total is greater than the sum of the parts. Sometimes you’re just lucky. We hit on it with that first trio album. Something Special.

TR: Another legendary collaboration was with Townes Van Zandt.

EA: I met Townes in 1967 at the Ohio Folk Festival. We were friends ever since. In the ‘80s we got close. I’d stay with him when I went south and he’d stay with me in New York. We wrote four tunes together.

TR: Which songs?

EA: They’re all on You Can’t Relive The Past..Let’s see, Meadowlark, The Road, The Blue March, and Night Train. As far as I know, it’s the only time Townes never co-wrote with anyone else.

TR: He was drinking quite a bit by that time.

EA: Yes. But, it was really for maintenance then. But, he could drink and do anything at the same time. Townes was the greatest southern songwriter since Hank Williams.

TR: Tell me about your process of songwriting.

EA: I’d really like to get the melody together at the same time as the lyrics. But, writing is my first love. I was always musical, but it would flow through what I was expressing in words. Sometimes, you’re trying to express something and you don’t even know what it is you’re trying to express. It just comes through the air, like you’re taking dictation and then you have to fit the music to it. I hear the rhythm, I pick a bit, but I don’t seek, I find. Picasso said that. Writing for me is a form of exploration. It’s like walking the sandy bank by the river, I don’t know where the source is, but it becomes more about the journey than the destination. You just report the beauty of what you see as you go along. Sometimes the songs come and they’re finished. It’s not always like (Leonard) Cohen. He works very hard sculpting and crafting the song to get it down to the right thing, sometimes revising, sometimes not. But, the first thought is the best, sometimes. And sometimes, the first thought leads you to the best thought.

EA: I’d really like to get the melody together at the same time as the lyrics. But, writing is my first love. I was always musical, but it would flow through what I was expressing in words. Sometimes, you’re trying to express something and you don’t even know what it is you’re trying to express. It just comes through the air, like you’re taking dictation and then you have to fit the music to it. I hear the rhythm, I pick a bit, but I don’t seek, I find. Picasso said that. Writing for me is a form of exploration. It’s like walking the sandy bank by the river, I don’t know where the source is, but it becomes more about the journey than the destination. You just report the beauty of what you see as you go along. Sometimes the songs come and they’re finished. It’s not always like (Leonard) Cohen. He works very hard sculpting and crafting the song to get it down to the right thing, sometimes revising, sometimes not. But, the first thought is the best, sometimes. And sometimes, the first thought leads you to the best thought.

TR: For most songwriter’s it’s a form of storytelling.

EA: Yeah. And if you knew where the story was going to end, you wouldn’t bother writing it. I try not to have a formula. It’s exploratory. It’s about breaking the borders, the wall, the limits of songwriting. Format is boring. If you can go against the usual verse/chorus, you try to strike out and break down the walls, rupture the borders, to come up with something different. You hope you can get songs that can do that. It’s important to push it further along. When I first started writing songs, there was only a handful of people. Those who had come before were Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, the Delta and Chicago blues guys. As the years went by the singer-songwriters multiplied and it seems like the subject matter diminished. It was hard to cover new ground. People became afraid to do new things. Some touched on politics, others turned inward, songs about ‘me,’ confessional songwriting. It just got less interesting over time. So, you had to try new things, new ways.

TR: You were there from the beginning of this great era of song.

EA. Yes. I was a witness for that scene: The birth of the singer-songwriter movement. I remember when the originals came to town, they’d play for six nights in a row. You’d hear people like Mississippi John Hurt, Rev. Gary Davis. They’d just move into town. I was a very fortunate witness to the birth of it all.

TR: One last question. Why did you move to the Netherlands?

EA: I met somebody over there and settled down. It was not such a major exile. You bring America with you. You know, I still wonder how the Yankees are doing every night before I go to sleep, even in the winter (laughs).

Terry Roland is an English teacher, freelance writer, occasional poet, songwriter and folk and country enthusiast. The music has been in his blood since being raised in Texas. He came to California where he was taught to say ‘dude’ at an early age.

ERIC ANDERSEN’S RIVER OF BLUE

FLOWS WITH A LEGACY OF SONG