Doo-wop – The Quintessential Folk Music

It may not be obvious on first listen, but doo-wop music is the quintessential American folk music. Before being co-opted by white record labels, doo-wop was almost exclusively the domain of young Black men gathering on street corners in Harlem, the North Side of Chicago, downtown Los Angeles, and other urban centers. It combined elements of what was then called “race music”—later known as rhythm and blues—blending gospel, Southern blues, jazz, and the early stirrings of rock and roll. But at its core, it was folk music: music of real people, for real people, heard in doorways, church halls, YMCAs, stairwells, and, most importantly, on the street.

It may not be obvious on first listen, but doo-wop music is the quintessential American folk music. Before being co-opted by white record labels, doo-wop was almost exclusively the domain of young Black men gathering on street corners in Harlem, the North Side of Chicago, downtown Los Angeles, and other urban centers. It combined elements of what was then called “race music”—later known as rhythm and blues—blending gospel, Southern blues, jazz, and the early stirrings of rock and roll. But at its core, it was folk music: music of real people, for real people, heard in doorways, church halls, YMCAs, stairwells, and, most importantly, on the street.

Doo-wop neighborhood groups filled the same niche that gangs often did, bringing (mostly) young men together to hang out and connect with one another and their communities. Harmonizing together was about friendship—it was a way to bond. When groups from other neighborhoods passed through, rather than fighting as some gangs might have done, these groups would engage in impromptu singing “battles.” A few notes were bent, but no blood was shed.

We tend to think of folk music as having rural roots—music played on front porches and back stoops of farmsteads, in slave quarters, sharecroppers’ shacks, and in the hollows and hollers of Appalachia and across the prairies. While it’s true that much folk music developed in rural America, it was in urban centers where various strains and influences came together, fueling an explosion of creativity in American music during the 20th century.

The Great Migration of Black people from the South into urban centers—where they hoped for less discrimination and greater economic opportunity—brought together people from different backgrounds and traditions. This blending of styles and influences created jazz, blues, rock and roll, and folk. Doo-wop emerged from the same cultural convergence: a fusion of musical traditions, but anchored most of all by rich vocal harmonies. This amalgamation generated not only friction but also collaboration, and the result was not just more—it was new. It was a creative engine that helped power American music and culture.

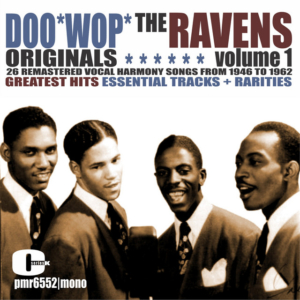

Doo-wop developed after World War II, building on the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance in poetry, music, and art, as well as the heightened aspirations of returning Black soldiers and their determination to be heard—and to be unapologetically Black. Its growth was also made possible by the increasing size of urban Black populations, which allowed for commercial success through support from local communities via record sales, club dates, and a vital boost from urban Black radio.

For many of these groups, singing was more than a recreational activity. Inspired by the mainstream success of earlier vocal groups like the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers, the young men singing under street lamps aspired to fame and recognition. Being young, Black, and mostly poor, success was hard to come by—but some made it. Still, like so many Black performers of the time, many doo-wop groups were exploited—paid little or nothing while others took the profits and much of the credit. Yet the music endured, and it inspired rock and roll, soul, Motown, and so much more.

You can listen to a one-hour program on the history of doo-wop—featuring The Orioles’ Crying in the Chapel, Hank Ballard and The Midnighters’ Work With Me Annie, The Five Keys’ The Glory of Love, The Moonglows’ Sincerely, The Drifters’ There Goes My Baby, and many more—on Mixcloud.

Ron Cooke is the author of a book of short stories and poems entitled Obituaries and Other Lies (available at Amazon); writes a well-received blog (ASSV4U.com/blog); and hosts a weekly radio show called Music They Don’t Want You to Hear on KTAL-LP in Las Cruces, NM. He is also a founding director of A Still Small Voice 4U, a not for profit supporting arts, culture and community that presents folk concerts, sponsors artists, festivals and community groups. Ron is an avid cyclist, racer, blogger, sculptor and ne’er-do-well.