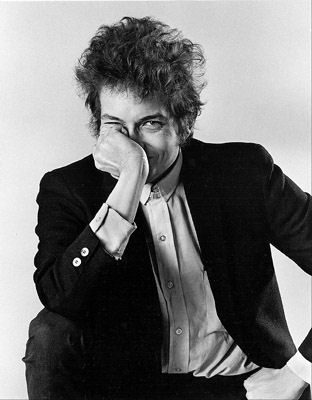

DON’T LOOK BACK?: BOB DYLAN: PHOTOGRAPHS BY DANIEL KRAMER

Don’t Look Back?: Bob Dylan: Photographs by Daniel Kramer

The Grammy Museum Exhibit – February 29, 2016—May 15, 2016

5/13/2016

A small Paris bistro, a chess board on the table, and Bob Dylan contemplating his next move—that’s all it took for Daniel Kramer to create an iconic image of the folk singer about to turn rock star in an iconic series of portraits of America’s greatest songwriter in 1964 and 1965—over 50 of which now adorn the LA Grammy Museum 2nd Floor Exhibit of Kramer Does Dylan which will be up through May 15. It’s a remarkable example of being at the right place at the right time, for Kramer’s collected photographs constitute not only a portrait of the artist as a young man, they raise Dylan into a symbol of the decade that defined us as a nation.

Until Kramer came into the picture, Dylan was best known for the photographic images of the rough-hewn folk persona he introduced to Gerdes Folk City in 1961 and ‘62—grainy brown leather jacket and Levis, harmonica holder and vintage Gibson acoustic guitar with strings wildly curling out of the headstock tuning pegs like his hair tumbling out of the Huck Finn cap on top—up to the Times, They Are A-Changing album cover of January, 1964—fixed in our minds as the Second Coming of Woody Guthrie. All that was about to change when Daniel Kramer heard “something I had never heard before—a public entertainer singing about the murder of Hattie Carroll—a Negro maid in Baltimore in 1963—by a son of privilege. That one song inspired Kramer to seek out a meeting with the folk singer whose work made him realize that “There was something new here—whatever it was.” “A good photographer needs a good subject;” he added, echoing what Walt Whitman said about poetry, and Kramer had found his, which culminated in the iconic album cover of Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home—(which won the Grammy for best album cover in 1964).

Kramer went up to Woodstock, where Dylan then lived with his wife Sara Lowndes Dylan and a growing family, and asked him if he could spend an hour with him, taking pictures. The hour stretched into three hours, and eventually stretched into two years. Dylan was constantly in motion, both physically and spiritually, and did not like having to pose for prepared studio shots. Kramer therefore for the first time began to just follow him around, and take pictures as they presented themselves—in real life.

That’s what makes the exhibit so constantly surprising—catching the moments of a great artist’s life—even sitting down at the typewriter to work on a song. It also captures Dylan’s sense of humor, as scenes unfold in real time back stage at a concert in Forest Hills Stadium in New York—yes, the same place that introduced the Beatles to America in 1964. In Dylan’s dressing room his then girlfriend Joan Baez is standing in front of him making faces at the camera, while Bob stretches her long black hair out to the sides and irons it like it was a blouse. It’s an utterly charming shot of the young lovers creating a memorable scene out of one stage prop—the iron—and two fertile imaginations in perfect sync with each other. Kramer was there to capture a one-time moment that keeps them forever young—in the words of a later Dylan song, written when he was old enough to notice time slipping away. That was in 1969, written for the birth of his first son, Jakob. This coming May 24 the singer turns 75, the perfect time for this retrospective. So much for Don’t Look Back—the 1967 D.A. Pennebaker film documenting the latter time period of these still photos. Dylan is looking back now with a vengeance—from his most recent (and upcoming) album of classic American songs from Frank Sinatra’s repertoire to the 2014 publication of The Lyrics: Since1962—weighing in at a hefty13 pounds—to the boxed set of complete sessions from 1965 to 1966—The Cutting Edge—to the major archive collection of manuscripts sold for $20,000,000 and housed at the University of Oklahoma Woody Guthrie Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma—to this traveling exhibit of photographs taken during the height of his mid-sixties fame as the voice of a generation. And all this is going on while we await the second volume of his memoir Chronicles—telling his story in his own words. Who knew that Dylan would turn into the Marcel Proust of his generation—obsessed with Remembrance of Things Past?

Daniel Kramer had only the most basic camera at the time—a 35 millimeter that he used for all occasions. But he realized that to take live shots of a major venue he would need something he couldn’t afford—a wide angle lens. A photographer friend of his rallied to the occasion, and simply gave him his own, with the parting words, “Now you have no excuse.” Kramer was able to move from the dressing room and small scenes to panoramic vistas of a folk singer in the process of becoming a rock star, with backlighting that would reinforce the aura of mystery surrounding Dylan in performance. They are stunning shots, especially one with Baez facing him in a duo at a concert in New Haven, Connecticut. It’s like looking at the twin Gods of folk music—on Mt. Olympus reshaping the hopes of a decade of change—perfectly framed and yet suggesting limitless horizons outside the frame. Wow! Long before Diamonds and Rust entered the picture—and they had both moved on, never to return.

That is the power of a photograph—it freezes time and fifty years later can reassert the dreams that came true, as well as those that crashed on the rocks. In a sense Dylan’s songs are also photographs in time, and the Grammy exhibit immeasurably enhances the still life with two walls of live performances on screen, and audio recordings as well, so Dylan’s presence is vivid in portraits of both sight and sound.

For that credit Grammy Museum Curator Crystal Larsen, who was generous in providing a press pass for me and guest Jill Fenimore.

To really complete the tour, however, the viewer should get on the elevator to the 4th floor, where they have an exhibit of the Kingston Trio and America’s Folk Roots. This is a time traveler’s delight, with both detailed Timelines of the folk revival going all the way back to Lead Belly’s birth in 1888, and a mesmerizing photo of his famous Stella 12-string—on which he became “King of the 12-String Guitar—and a page from Woody Guthrie’s FBI file from his days with the Almanac Singers.

It’s a brilliant tour through the Red Channels chapter of the folk revival, including a classic early concert poster of The Weavers with my personal favorite folk singer—a young Ramblin’ Jack Elliott described as “singing cowboy songs and Woody Guthrie songs,” a video interview with Pete Seeger recounting his unfriendly witness testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities on August 18, 1955—in which he not only refuses to answer their questions, but chooses not to do it on the basis of the 5th Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination—taking instead the more provocative and dangerous path of relying on the 1st Amendment protection of Freedom of Speech. As Pete said, “The 5th Amendment says they have no right to ask me such questions; the 1st Amendment says they have no right to ask any Americans such questions—especially under duress.” Again, on the wall, now behind glass for all to see, is the actual Congressional Record (from the Government Printing Office) with the astonishing title: The United States of America vs. Peter Seeger. In 1961 the United States Supreme Court found in Pete Seeger’s favor and overturned his Contempt of Congress citation to keep him out of prison.

And just a couple of frames away is the actual handwritten yellow legal pad manuscript page of Bob Dylan’s first published song from his eponymous first album in 1962—Song to Woody. The footnote—also handwritten, opens up a new world; it says in full, “Written by Bob Dylan in Mills Bar on Bleecker Street in New York City—on the 14th day of February—for Woody Guthrie.” Think of them as links on a chain.

As if by divine providence, it was written as a love song, on Valentine’s Day—the birthday of a new folk era; and thanks to the Grammy Museum, still and forever young.

Bob Dylan: Photographs by Daniel Kramer will be up at The Grammy Museum until May 15th; With thanks to Crystal Larsen for the press pass!

May 20 is the release date for Fallen Angels—the second volume of songs from the Great American Songbook associated with Sinatra; on June 16 Dylan appears in concert at The Shrine Auditorium with Mavis Staples opening. See Bob Dylan’s website for tickets.

May 22 at 7:00pm Ross Altman and others perform at Beyond Baroque in a Million Dollar Bash Forever Young 75th Birthday tribute to Bob Dylan—for his birthday May 24.

Los Angeles folk singer and Local 47 member Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature; Ross may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com