Did I Say That?

A Talmudic Commentary On Who Wrote Dylan

You know you are reaching the end of the road as a writer when the best you can come up with is a commentary on your own previous work, but I happen to have a rabbi-and when your rabbi asks you to do something, you don’t ask questions, you do it. My rabbi addressed the following letter to me after reading my column, Who Wrote Dylan:

You know you are reaching the end of the road as a writer when the best you can come up with is a commentary on your own previous work, but I happen to have a rabbi-and when your rabbi asks you to do something, you don’t ask questions, you do it. My rabbi addressed the following letter to me after reading my column, Who Wrote Dylan:

Ross:

A clever rejoinder and fun to read. However, I wonder whether you might do some musing on the darker issue, here, which is: what gives?? There is a time honored tradition of artists changing their names (both music, stage, film and rock). Why is Dylan singled out by her? And the stage persona vs. actual personality? Nothing new, there, either. So, what gives? (And, most serious is the plagiarism charge. Exactly how many tunes, lyrics, etc. arise sui generis? Is there not a long history of musical influences or even the use of phrases that one might use to craft a different product?)

So what is really going on, here? Has not Joni herself adopted various persona: wayward California hippie chick; expatriate? Jaded loved, etc., etc.? What’s the difference between poses and falsity? What’s the connection, exactly between genuineness and art? If a songwriter writes a song from another’s point of view and doesn’t just write about their own life and experiences are they phonies or inventive, creative, artists?

Now, there might be some legitimacy to the question of whether a white man can sing the blues, in other words, is there a criterion of authenticity that might be applied as a standard to artists but that is only one criteria of many, and certainly, posing as opposed to trying to pass is no crime. Is she pissed that Bob Dylan’s dream about riding on a train going west seems to indicate that he was a hobo when he never (probably) saw the inside of a freight train in his life? Is it the obligation of an artist to make clear to his audience what is real and what is not in his work?

Just some small rants as I read her piece and yours.

Best,

Rabbi

Dear Rabbi,

When Jonathan Swift published A Modest Proposal he was attacked mercilessly for suggesting that England should best solve its problem of poverty by devouring its young-feeding roasted babies to the poor, who had no better source of nutrition. The most brilliant piece of satire in the English language had been misunderstood as proposing seriously a policy he had deliberately exaggerated to an extreme degree in order to poke fun at the British, who in Swift’s eyes were already in effect devouring the children of the impoverished Irish, whom Swift was valiantly defending. The exaggeration was essential to the humor, and those who mistook its satiric intent for a serious suggestion of social policy might as well have been reading in a foreign tongue, for Swift’s purpose in writing was utterly lost on them.

Mark Twain fared little better when he satirized Christian missionaries by apparently suggesting they be roasted alive to feed the natives they were trying to convert, again being misunderstood as the price of using every weapon in the writer’s arsenal to make a withering critique of the most sanctimonious religious zealots among us. Mark Twain no more wanted to feed Christians to the lions than Swift wanted to feed babies to the Irish, but he understood that sometimes the best way to reveal the truth about hypocrisy is to poke fun at it until the stuffed shirt pops.

To be great is to be misunderstood said Emerson, but it does not necessarily follow that to be misunderstood is to be great. I therefore make no boast that my similarly intended satire of the Earl of Oxford true believers, who have convinced themselves that he, and not William Shakespeare, wrote the plays attributed to Shakespeare, a satire I built on the sturdy edifice of America’s greatest songwriter-that would be Bob Dylan-is in any sense on the order of the best known satires of Swift and Twain.

But I can say that I have been equally misunderstood-as taking seriously Joni Mitchell’s strangely self-serving and I thought self-evidently preposterous claim that Dylan is a plagiarist, and that therefore someone else must have written his songs. That was nothing more than a literary pretext to launch my satire of the many and varied stuffed shirts-mostly outside of academia-who similarly claim that Shakespeare did not write his own plays, but a member of British royalty did.

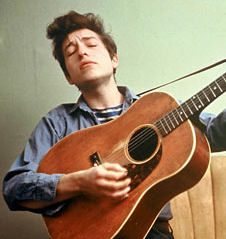

And yet enough readers took my satire literally, and came away believing that I accepted at face value Joni Mitchell’s sour grape assessment of her fellow Rock and Roll Hall of Famer that it behooves me now to set the record straight with my own actual responses to this controversy, one that has pitted Dylan’s defenders (cf. Sean Wilentz) against his detractors (Jonny Whiteside). Those who are even casually familiar with my essays over the past ten years will recognize as absurd the claim that I would think Prince Charles or anyone else had actually written Bob Dylan’s songs; the whole point of my essay was to highlight how equally absurd it would be to think that the Earl of Oxford had written Shakespeare’s plays. The reason I chose Dylan as my literary foil in the effort to lampoon the baseless claims of the Earl of Oxford’s descendants and their idiot champions (some of whom are on the Supreme Court) is precisely because of the unassailable magnitude of Dylan’s body of work, the only contemporary American songwriter whose name can be mentioned in the same sentence with Shakespeare without apology or irony.

And yet, there is no gainsaying the fact that Dylan has been dogged by charges of being-shall we say-under the undue influence of his varied poetic sources for a good part of his career, and it is not entirely an accident that the word plagiarism has occasionally surfaced to tarnish his reputation. After all, he did adapt the tune for Blowing in the Wind from the antislavery spiritual No More Auction Block Over Me; he did adapt the tune for his early love song Fare Thee Well from the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem’s version of The Leaving of Liverpool; he did adapt the tune for Bob Dylan’s Dream from English folk singer Martin Carthy’s version of Lord Franklin; he did adapt the tune and point of view for With God On Our Side from Irish playwright Dominic Behan’s The Patriot Game; and he did adapt the tune for Farewell Angelina-which he wrote for Joan Baez-from her rival Judy Collins’s version of the traditional Scots’ Farewell to Tarwathe.

But if that is plagiarism then most of folk music is plagiarism. For Woody Guthrie adapted the tune for This Land Is Your Land from the Carter Family’s Darling Pal of Mine; Pete Seeger borrowed the tune for Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet’s The Little Dead Girl Of Hiroshima (I Come and Stand at Every Door) from James Walter’s music for the Childe Ballad The Great Silkie; Julia Ward Howe borrowed the tune for The Battle Hymn of the Republic from the traditional John Brown’s Body; and Ralph Chaplin borrowed it from her for his labor anthem Solidarity Forever.

George Gershwin adapted the music for Summertime from the Negro Spiritual Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child-and was proud of it, quite deliberately doing his research for Porgy and Bess in black churches to absorb as much of their singing as he could; Love Me Tender, one of Elvis’s biggest hits, used a Civil War song melody, as did Goebel Reeves Hobo’s Lullaby; Oscar Brand borrowed the tune for When I First Came to This Land from Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star, which (Pete Seeger first noticed) borrowed it from Mozart; and Josephine Daskam Bacon borrowed the tune for A Hymn for Nations from Beethoven’s 9th Symphony.

And yet one never hears the charge of plagiarism bandied nonchalantly around except in reference to Bob Dylan’s borrowings and adaptations. Rather one hears the words the folk process to describe what is the time-honored method of recreating new songs out of old-the same method Woody Guthrie used in Pastures of Plenty (adapted from Pretty Polly), Union Maid (borrowed from Redwing), and The Sinking of the Reuben James (adapted from Wildwood Flower). The only meaningful way to look at Bob Dylan’s overlay of traditional music and imagery onto his own original and increasingly inventive early works of genius is to understand them as the outpourings of a genuine folk poet and folk singer-no less so than Woody Guthrie, and one who would soon travel down roads completely of his own that even Guthrie would have been a stranger to, whose more personal and often surrealist works of imagination still harbor unplumbed depths of mystery over forty years after they burst on the modern American landscape like Picasso burst on the world of traditional painting in the early 20th century.

Bob Dylan is the most original and demanding American songwriter of the 20th century, and everyone else in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame who is still alive understands that they may be in the same hall with him, but they are not on the same planet. Everyone but Joni Mitchell, and just like those who fervently believe that the Earl of Oxford wrote Hamlet, she is entitled to her opinion, one that is unworthy of a great artist.

To appreciate in literary terms what Dylan accomplished in his transition from early protest singer to a songwriter of personal, introspective and poetic vision, in which period he wrote his most original and powerful songs, I am drawn to the useful framework Yale critic Harold Bloom developed in The Anxiety of Influence.

Adapting Bloom’s methodology to Dylan, one observes that Dylan began under the influence of Woody Guthrie to write protest songs, and when he had gone as far as he cared to go in that vein he first felt compelled to reject it by dismissing them as “finger-pointing songs” before he could go on to write songs that were not subject or event-driven, but came from a deeper place, one in which he created a new landscape for American songwriting, and in Bloom’s phrase, was able to achieve his own individuation as a poet. That is a variant of the same process every poet must undergo to find his or her own voice, so to single out Dylan as a “plagiarist” for wearing his influences on his sleeve is demonstrably unfair. If one wants a higher authority in this regard, I refer you to the Nobel Prize winning poet of 1948, T.S. Eliot, who memorably said in his classic work of literary criticism from 1922, The Sacred Wood: “Bad poets imitate; good poets steal.”

Or as Woody Guthrie put it when advised that another folk singer was “plagiarizing” his work: “Ah hell; he just steals from me-I steal from everybody.”

The point surely is that Bob could never hide his sources, or tried to: he was too well known practically from the very beginning to pass off as his own something derived from another. It was precisely his indebtedness to the folk tradition, and his constant mining of it, that distinguished his work from that of others of “Woody’s children.”

My rabbi raises other questions that warrant consideration, but they will have to wait for another time, another place. I will end by plagiarizing from myself, from a brief piece I wrote in response to an earlier (2001) dustup about Bob’s album, Love and Theft:

Dear Bob, Please Steal This Column

Hey Bob, I hear you stole about twelve lines from an obscure Japanese book called Confessions of a Yakuza, about a Japanese gangster. One of your fans who teaches English in Japan happened on the book and noticed a remarkable sameness between lines in the book and lines from your latest album Love and Theft. He posted those borrowings on one of dozens of Internet sites devoted to scrutinizing every detail of your work and-voila-first The Wall Street Journal and then The Los Angeles Times picked up the story.

The immediate effect was that sales of Confessions of a Yakuza jumped from 85,000th place on Amazon.com to the top 200. Generously, the author announced he had no interest in suing you, but thought it would be honorable of you to credit his book as source material on the next printing of your album. He would also like you to plug his book for the next edition.

Which brings me to the subject of this column. Please steal it, Bob. I don’t need it, don’t want it, have no interest in it. It’s yours. Stick it in a song. Whistle it while on your way to work. Post it in one of your chat rooms. Whoever might want to sue you for copyright infringement, I can say unequivocally no, no, no it ain’t me, babe.

I will go further-if you don’t steal it, Bob, you’ve got a lot of nerve to say you are my friend. When I was down you just stood there grinning. You’ve got a lot of nerve to say you’ve got a helping hand to lend. You just want to be on the side that’s winning.

Perhaps you haven’t heard, Bob, but someone’s got it in for you-they’re planting stories in the press. Whoever it is I wish they’d cut it out quick, but when they will I can only guess.

Yes, Bob, I received your letter yesterday, about the time the doorknob broke. When you asked me how I was doing, was that some kind of joke?

Moreover, it ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, Bob, ‘cause the answer is blowing in the wind. I know things have changed, but even if they lock me up for what I am urging you to do, I shall be released.

Besides, Bob, you know I’ve paid some dues getting through, and I can’t waste any more time talking to the servants about man and God and law, so whatever you say, I ain’t, repeat ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more.

Please don’t put a price on my soul, Bob, just steal this column and put it on your next album.

Thank you,

—“Tangled Up in Blue”

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com His PhD is in English.

Did I Say That?

A Talmudic Commentary On Who Wrote Dylan