BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME:

The Meaning of Bob Dylan's Nobel Prize in Literature

“Mama put my guns in the ground”

Guns-a-blazing, Bob Dylan kicked the door wide open to the notion that songs are poetry. After the smoke cleared, many of us innocent bystanders struggled for decades to argue that songs sung can be and are literature. (Ineffectively, it seems.) And some of us were arguing this before Dylan’s in-bursting outburst.

In 2016, however, our argument was recognized and championed in a way we had not dared to imagine: Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Literary Folk Are We

This changed the definition of literature as much as it changed the definition of folk music. It also blurred the distinctions between both. This is a good thing because the distinctions, in reality, have always been so blurred as to Not Actually Exist.

I had expected some stuffy blowback from academia. Almost immediately, in “The World Does Not Need Bob Dylan, Nobel Prize Winner in Literature.” Matthew Schnipper insists that the committee should “celebrate someone whose work the world may not know.” Since this is not how Nobel Prizes work, this should put Schnipper, the then executive editor of Pitchfork, “the Most Trusted Voice in Music,” out of bounds for criticism. [His editorial is now significantly changed since its first appearance.]

Poets Jack Kérouac, Bob Dylan, and Allen Ginsberg

His trustworthy ignorance aside, his misunderstanding of the significance of the event seemed to me part of a general chorus arising from the rock intelligentsia: The prize should have gone to a Real Writer.

“It’s weird,” wrote Schnipper in the original version of his opinion piece. “They gave one of the world’s biggest literary prizes, to a singer-songwriter. . . . [Dylan is] a musician and his relationship with words is as a lyricist, someone whose prose [sic (lyrics, by definition, are not prose.)] exists inexorably with music.” However, the poetry of Shakespeare (to whom Dylan humbly compared himself in his acceptance speech) also exists inexorably with its metrical forms and its rhyme schemes — what we call prosody.

Flat Readings

“To read [Dylan’s] lyrics flatly, without the sound delivering them,” Schnipper concluded, “is to experience his art reduced.” Schnipper had forgotten something: to read Hamlet’s soliloquy flat, without the sound of Richard Burton or Mel Gibson delivering it, is to experience Shakespeare’s art reduced also. The same could be said of the plays of Eugene O’Neil, Harold Pinter or any playwright.

As certainly as Shakespeare, O’Neil, and Pinter wrote their words on paper first, so did Bob Dylan. In the same way, Winston Churchill wrote the oratory that gave Britain and her allies such courage and resolve during the Second World War. O’Neil won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936; Churchill won it in 1953 and Pinter in 2005.

As certainly as Shakespeare, O’Neil, and Pinter wrote their words on paper first, so did Bob Dylan. In the same way, Winston Churchill wrote the oratory that gave Britain and her allies such courage and resolve during the Second World War. O’Neil won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936; Churchill won it in 1953 and Pinter in 2005.

“We already know Dylan is a genius,” Schnipper now declares. Thus, he avoids arguing that Dylan, as author of much high and heavy handed pretentiousness, should be disqualified from consideration. Even though Dylan, to quote a peasant in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, “got better,” it’s a good argument. However Schnipper does not make it. Nor did he make it in the original version of his op-ed.

Outside Academia

INSIDE ACADEMIA: In 2004, Bob received an honorary doctorate from the University of St. Andrew’s in Scotland for “outstanding contribution to musical and literary culture.”

So why did Bob Dylan deserve the Nobel Prize in Literature? Almost single-handedly, Dylan replaced prosody with musical forms that prosody had replaced. He did this completely outside academia and he did it in a completely non-academic way. He was not trying to discover and restore the exact musical forms that prosody had replaced; he was only interested in the forms close at hand.

He wasn’t trying to reproduce how the Odyssey or the Iliad sounded when Homer and other ancients sang them [though both were influential, as we would find out when Dylan recorded his Nobel Lecture in Literature]. He wasn’t researching British ballads or Scottish harping to discover how Beowulf might have been sung in its original form. Nor was he arguing that literacy had replaced organic musical prosody with less organic, if not intellectual, forms such as the sestina with its mirroring rhyme schemes.

The Tape Recorder Giveth What the Printing Press Tooketh Away

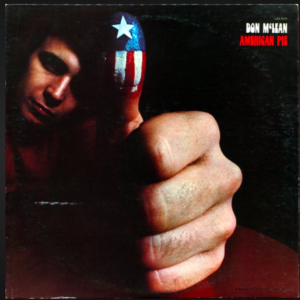

“A long long time ago…”

Marshal McLuhan published The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man in 1962. Two years later he would declare “the medium is the message.” Not quite a hundred years earlier, however, Francis James Child, Harvard’s first Professor of English and the father of ballad scholarship, fully understood the role of the printing press in the making of folk music. Would he have understood the role of the tape [or digital] recorder in the unmaking of folk music?

Dylan instinctively knew that the hegemony of the printed page was finished and that the very word ‘literature’ was obsolete if not classist. Recording technology meant that poetry could be sung again. Not that Dylan was at all interested in proving this. His purpose was quite different and —being non-academic— immediate.

Bob Dylan gets writing tips from Woody Guthrie in a classic SNL skit

To position himself as the heir apparent to Woody Guthrie he had come across the ballads in their American hiding places: Appalachia and the Ozarks. He had come across similar narrative forms used in African American communities.

The antiquarian and aesthetic aspects of folk material were of secondary importance to Guthrie and associates. It was the music of and for the downtrodden who, of course, were America’s impoverished and uneducated — people who had for centuries been the caretakers of pre-literate forms of poetry such as ballads. In Britain, singing Marxists like Ewan MacColl and A. L. Lloyd [no relation], saw in these songs the voice contemporary labour unions. They acted accordingly.

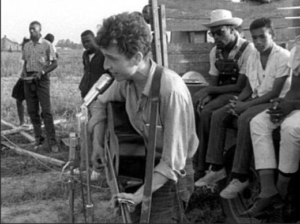

Bob Dylan in 1963 singing in Greenwood, Mississippi about the murder of activist Medgar Evers

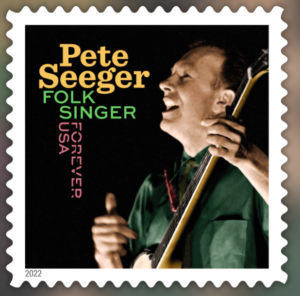

Pete Seeger Forever

The primary importance of this music was in how easily it could be used to communicate the grievances of and shameful injustices committed against disenfranchised people, injustices in-progress at the time. Guthrie prided himself in his ability to work seamlessly and quickly in these forms. Young Bob Dylan discovered he was just as able and perhaps more agile. And thus he came to the attention of Pete Seeger and producer John Hammond.

And that might have been that. But Robert Zimmerman was a poseur, an arrogant thief, a liar and self-aggrandizer. He was spiteful and ungrateful. He was also smart and fearless. What else he was and is I do not know. However, these were the characteristics which allowed him to see that he had taught himself a lost form of poetry and if it was poetry he could throw anything he wanted at it. The more unlikely the content, the taller Bob Dylan stood. The argument that Dylan’s early poetry, read or sung, reveals nothing more than a sort of barnstorming juvenilia is beside the point. His barnstorming juvenilia had rescued poetry from academia and the printed page. And it did so with nobody’s help or approval.

His retro-revolution in form aside, the content of Dylan’s songs are often thoughtful, sensitive, beautiful. “She Belongs to Me” and “I Shall Be Released” come to mind. He has written songs of great lyrical power.“All Along the Watchtower,” “Hurricane,” “Blind Willie McTell,” To quote the Python peasant again , he “got better.”

“Hurricane,” cowritten with Jacques Levy [1935 – 2004], Schnipper calls an “anthem . . . about the false imprisonment of Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter.” Schnipper neither knows nor understands the names of the basic forms of the music which he critiques. As any trusted voice in music should know, “Hurricane” is not an anthem but a ballad strong enough to rival any in the Anglo-Celtic tradition, a  tradition that Dylan knew very well. It was also strong enough to be a primary catalyst in Carter’s eventual release. From the very start of his career, Bob Dylan wrote songs to foment social change and right egregious wrongs. “Hurricane” caps that endeavor.

tradition that Dylan knew very well. It was also strong enough to be a primary catalyst in Carter’s eventual release. From the very start of his career, Bob Dylan wrote songs to foment social change and right egregious wrongs. “Hurricane” caps that endeavor.

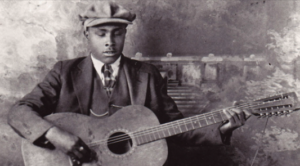

“I know no one can sing the blues / like Blind Willie McTell.” — Bob Dylan

“Blind Willie MacTell” is a tour de force encompassing the whole of the Anglo/Celtic/American song tradition Dylan knows as well as you or I know the neighborhood in which we grew up or now live. The song is alive with twisted yet familiar symbols and archetypes. We are taken back to the land of cotton, enslavement, and that genius-riddled sung poetry we call the blues — the heart of our world. It could be a protest song. But it’s not. It’s a celebration.

Matthew Schnipper is right: “We know Bob Dylan is a genius.”

Bob Dylan opened the door for all of us. He deserved the Nobel Prize in Literature.

This is a revised and expanded version of an essay DNL first posted at davidnigellloyd.com on January 3rd, 2017.

David Nigel Lloyd

Working on the periphery of American and British Isles folk traditions, Guitarist/song-poet David Nigel Lloyd built a small but international reputation while working professionally as an arts advocate and teaching artist in the California counties of Kern and Siskiyou.

He accompanies himself on the 8-stringed octar, and on guitar in modified lute tuning tuning. DNL has performed at folk venues in the British Isles, Canada and throughout the US. He is known to introduce his songs with jokes, True Facts, Tall Tales, and Outright Lies.

David Nigel Lloyd’s website

BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME:

The Meaning of Bob Dylan's Nobel Prize in Literature