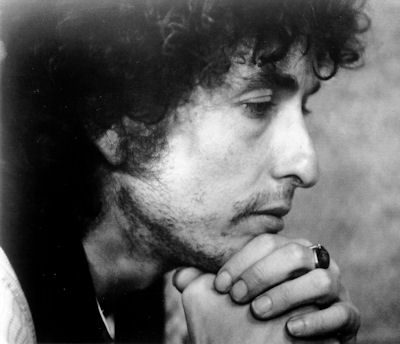

BOB DYLAN’S NOBEL LECTURE:

BOB DYLAN’S NOBEL LECTURE:

I Shall Not Be Released

6/14/2017

The first thing you learn from the Nobel Prize web site with regard to Bob Dylan’s long-awaited and worth waiting for lecture—to fulfill the final requirement of his Nobel Prize for Literature—is that all rights are reserved and it may not be reprinted in any form, though the audio file may be embedded in other web sites—which FolkWorks has already done. But as for the text, it shall not be released. Perhaps that augurs that Dylan himself has plans to reprint it in an official form someday. (The text is reprinted in full on the Nobel Prize website, noted below.*) It is a brilliant lecture on the foundational role classic literature played in the writing of his songs, and for those who may have wondered whether his selection as the 2016 Prize recipient was worthy of the name literature—his insights into three of the literary classics he celebrates should put that question to bed once and for all. Dylan here talks in the role of a professor of literature who without question has immersed himself in the same canon of masterpieces that would be expected of any such Prize recipient. He has clearly read the classics, understood them in a profound way, and used them in ways no other modern songwriter has come close to matching. Dylan’s lecture is itself an introduction to literature.

It was delivered and recorded on June 5th, 2017, the 49th anniversary of the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy—when the 1960s for all intents and purposes came to an end. It was therefore the perfect time to have delayed until to give such a lecture to mine the sources for the quintessential voice of the ‘60s. Dylan traces the underpinnings of many of his (unnamed) songs to three essential literary classics—Moby Dick by Herman Melville, All Quiet On the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, and the Odyssey by Homer—the only author he mentions by name.

One does not have far to search to discover the most likely candidates for songs inspired by Dylan’s Hibbing, Minnesota grammar school reading—which certainly is a testament to the highest quality grammar school one might wish for—since I didn’t become introduced to these words and works until high school on the Westside of Los Angeles. Dylan quotes from them freely, indicating how deeply they became a part of his imagination at an early age.

To begin where he does, with a book many recommend as The Great American Novel—before Philip Roth appropriated the phrase for an actual novel—Dylan wrote his own acerbic version of Melville’s masterpiece in his fifth album—Bringing It All Back Home—which also alludes to the Odyssey—in his 115th Dream, where he recounts the wild adventures he has “riding on the Mayflower” which was headed by “Captain Arab,” who said:

Boys, forget the whale

Look on over yonder

Cut the engines

Change the sail

Haul on the bowline…

and then suddenly you are transported to his founding father creation myth:

I think I’ll call it America

I said as we hit land

I took a deep breath

I fell down I could not stand

which elides into the betrayal and theft of the country from Native Americans:

Captain Arab he started writing up some deeds

He said, “Let’s set up a fort

And start buying the place with beads.”

It’s one of Dylan’s brilliant satires, and climaxes with the revelation that the Pequod—the name of Melville’s ship, which Dylan notes is named for an Indian tribe—landed before Columbus in 1492, making Moby Dick one of the founding documents of the new nation. In Dylan’s rhapsodic retelling, as they are leaving the bay, they meet “three ships,” the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria “heading my way.” And in the final line he wishes Columbus “good luck.” Without belaboring the point Dylan uses a classic work of American Literature to recreate American History as a trenchant social critic. It is absolutely brilliant—and in the age of Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation’s desperate struggle to retain their water rights from an 1851 treaty with the US Government—the current version of which are now in the process of breaking yet another treaty and giving their land to Big Oil companies for their exploitation.

The second literary classic Dylan pays tribute to is German novelist Erich Maria Remarque’s World War One masterpiece All Quiet On the Western Front. He says the book took such a hold on him that its exhaustively detailed portrayal of the suffering of soldiers during “the war to end all wars” gave him the chills such that when he finished it he vowed never to read another war novel—a promise he has kept. Dylan didn’t have to—he became the voice for those oppressed and obliterated soldiers in his 1963 antiwar song Masters of War, every line of which could be traced back to Remarque’s powerful account for inspiration. Likewise his second antiwar classic With God On Our Side, looks at America’s history of warfare through the lens of All Quiet On the Western Front, as the book in which Remarque documented his own firsthand experiences on the front lines, in which he was wounded with shrapnel in both his right and left arms, and his neck. Remarque transformed his personal experiences into a tragic portrayal of his generation whose lives were destroyed by the Great War—even if they survived—and which in turn transformed him into the “Militant Pacifist” he would later become.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7FKyouUIsQ

But the most personal antiwar song Dylan wrote—and which may also be credited to the influence of All Quiet On the Western Front—from which he quotes perhaps Remarque’s most powerful line, “At the age when we were just learning to love life and the world, we were trained to shoot it to bits.” That becomes Dylan’s song John Brown, a tale of a soldier who returns home to be met by his doting mother looking only for his medals. The song ends with her son—like Gary Cooper in High Noon tossing his badge into the dirt—tossing his medals into her hand. It’s the great image of someone who is finally able to answer Pete Seeger’s great question, “When will they ever learn?” Those are Dylan’s three most moving songs of war, and they may all find their genesis in Erich Maria Remarque’s novel of the First World War.

Here is another significant detail, however, Dylan leaves out of his account—All Quiet On the Western Front was the first book the Nazi’s burned when they came to power. They did not approve of its harrowing portrait of modern warfare—and how it might influence young Germans not so easily to be led into fighting World War II. They could not retaliate against its author, who lived in Switzerland at that point, but they took out their vengeance against his younger sister, Elfriede Scholz, who still lived in Germany. When she was interviewed she said that “the war is lost,” and the Nazis arrested her, tried her for undermining the morale of their soldiers, and then announced that though her brother and author was beyond their reach, she “will not escape us.” They found her guilty and—in an eerie foreshadowing of ISIS today—beheaded her. That was the price she paid for her brother’s antiwar classic. Remarque would later dedicate his 1952 novel Spark of Life to her.

The third literary classic whose influence Dylan explores to demonstrate how indebted his work is to classic literature is Homer’s The Odyssey—the story of how Odysseus slowing finds his way back to Ithaca and his wife Penelope after twenty years in exile. Dylan notes that he is not the only songwriter to be so influenced—and mentions Paul Simon’s Homeward Bound, Harlan Howard’s Green Green Grass of Home, and Home On the Range, with words by Dr. Brewster M. Higley and music by Dan Kelly. The Dylan song I would put at the top of that list is Like a Rolling Stone, with its Odysseus-drenched chorus as a jaded wanderer:

With no direction home

Like a rolling stone.

The most piercing question he raises and observation Dylan makes during this penetrating survey of Western Literature is to note that the great wisdom of the ancient Greeks in the philosophies of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle did nothing to stop World War I, or the depredations against the Native Americas, or indeed the Holocaust. It’s the same question asked by English literary critic George Steiner—whose groundbreaking book The Language of Silence looks at the place of both literature and classical music after the Holocaust, and wonders how language must be reinterpreted after it has been used to such purposes—where Nazi butchers would send Jews to gas chambers by day and listen to Beethoven, Mozart and Bach to unwind at night. That is a place Dylan does not really care to go—but he certainly opens the door to that kind of speculation.

We must be ever grateful to him—and to the Nobel Committee in Stockholm—for bringing the world of modern songwriting and its roots in traditional American folk music to the academy of what English critic F.R. Leavis called The Great Tradition. Only to Bob Dylan would it occur to bring old-time string band leader Charlie Poole from North Carolina into a discussion of Remarque’s World War I masterpiece, but here he is:

“Charlie Poole from North Carolina had a song that connected to all this. It’s called You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me, and the lyrics go like this:

I saw a sign in a window walking up town one day.

Join the army, see the world is what it had to say.

You’ll see exciting places with a jolly crew,

You’ll meet interesting people, and learn to kill them too.

Oh you ain’t talkin’ to me, you ain’t talking to me.

I may be crazy and all that, but I got good sense you see.

You ain’t talkin’ to me, you ain’t talkin’ to me.

Killin’ with a gun don’t sound like fun.

You ain’t talkin’ to me.’

That is precisely what makes Dylan’s Nobel Prize Lecture unique: he connects his work not only to the recognized masters of Western Literature, but to the folk music out of which he drew the same kind of inspiration. In the end he raises the art of song to the art of literature—which is what the Nobel Committee recognized and celebrated in its inspired choice for the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. Bravo on the Western Front, and on all fronts—including Dylan’s first inspiration—Buddy Holly, who fused “country and western, rock and roll and rhythm and blues into one brand”—where his essay begins.

Let me end with a word of gratitude to two of my own inspirations.

The first my longstanding English spiritual compatriot, friend and occasional FolkWorks colleague (to whom this essay is affectionately dedicated), Rosa Redoz, who teaches Shakespeare outside London. She suggested I write this review when she sent me this note immediately after Dylan’s words were made public:

Hi Ross

Just a quick note to say I’m hoping you are going to do a review of Dylan’s Nobel speech. It was lovely hearing extracts today, brought a bit of literary sunshine, which we could use right now…”

Take care.

Best wishes,

Rosa

And Rabbi Marx at the Santa Monica Synagogue, where the Santa Monica Traditional Folk Music Club meets the first Saturday of every month; who wrote in reply to my sending him the text of Dylan’s lecture:

“Yes, indeedy! And what a fine, fine piece of writing this is:”

“You know what it’s all about. Takin’ the pistol out and puttin’ it back in your pocket. Whippin’ your way through traffic, talkin’ in the dark. You know that Stagger Lee was a bad man and that Frankie was a good girl. You know that Washington is a bourgeois town and you’ve heard the deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a boggy creek. And you’re pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial boy. You heard the muffled drums and the fifes that played lowly. You’ve seen the lusty Lord Donald stick a knife in his wife, and a lot of your comrades have been wrapped in white linen.”

Let Dylan have the last word. Here is the link so you can enjoy reading him yourself:

* © THE NOBEL FOUNDATION 2017

The Nobel Foundation has not obtained the right to assign any usage right to the Nobel Lecture to any third party, and any such rights may thus not be granted. All rights to the Nobel Lecture by Bob Dylan are reserved and the Nobel Lecture may not be published or otherwise used by third parties with one exception: the audio file containing the Nobel Lecture, as published at Nobelprize.org, the official website of the Nobel Prize, may be embedded on other websites.

Los Angeles folksinger Ross Altman has a PhD in Modern Literature from SUNY-Binghamton; he is a member of Local 47 (AFM) and may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com