Bob Dylan Elected to American Academy of Arts and Letters

“A category mistake” is what philosophers call it: judging something that belongs in one category by the standards of another—for example, putting a rock musician into the pantheon of poets, artists and musicians who belong to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, such as Mark Twain, Robert Frost, Edmund Wilson, Arthur Miller, Ernest Hemingway, E.L. Doctorow, Malcolm Cowley and Kenneth Burke.

“A category mistake” is what philosophers call it: judging something that belongs in one category by the standards of another—for example, putting a rock musician into the pantheon of poets, artists and musicians who belong to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, such as Mark Twain, Robert Frost, Edmund Wilson, Arthur Miller, Ernest Hemingway, E.L. Doctorow, Malcolm Cowley and Kenneth Burke.

Well, the times, they are a-changing, because Bob Dylan, the Huck Finn cap-wearing Chaplinesque original vagabond from Hibbing, Minnesota just crashed the most exclusive party in American culture. My question is: what took them so long?

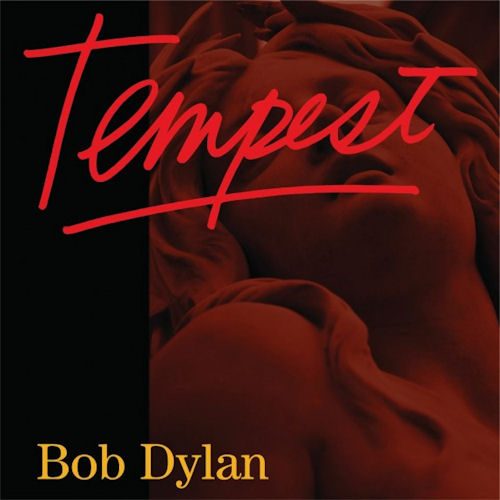

Tempest, his 35th studio album, released 50 years after his first eponymous album in 1962, was completely ignored by Grammy voters—not nominated in Folk, Americana or Rock categories—and seemed to sink as completely as the Titanic, subject of the title song. But even though the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences was Dylan’s iceberg, Tempest clearly caught the ears of a far more elite group of listeners—voting members of The American Academy of Arts and Letters—the American version (founded in 1904) of L’Académie Française, created by Cardinal Richelieu in 1635 as the guardian of the French language.

Dylan’s honorary membership in the American Academy represents a lifetime achievement, not for one album only, but Tempest reveals in riveting detail the literary scope of his major work that would make Academy members feel that he belonged in their club—the first rock musician to be so honored.

Consider the title: borrowed (without the initial article) from Shakespeare’s last play, which gave rise to speculation that this would be Dylan’s last album. It wasn’t his first nod to the bard:

Shakespeare he’s in the alley

with his pointed shoes and his bells

speaking to some French girl

who says she knows me well

(Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again);

and from Desolation Row:

Ophelia she’s ‘neath the window

For her I feel so afraid

On her 22nd birthday she already is an old maid

and later in the same song he imagines:

Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While Calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers

And perhaps his most famous put down of the pretension sometimes surrounding serious literature, from Ballad of a Thin Man:

You’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books

You’re very well read it’s well known

But something is happening here

And you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mr. Jones?

With your sheet metal memories of Cannery Row

(Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands)

Mine [relationships] have been like Verlaine’s and Rimbaud

(You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go)

I’ve read Erica Jong

(Highlands)

Well the last I heard of Arab

He was stuck on a whale

(Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream)

Dylan’s work has long been filled with literary allusion. Indeed, his very name has from the beginning been regarded as having a literary reference, despite Dylan’s tongue-in-cheek demurrer: “I’ve done more for Dylan Thomas than he ever did for me.”

His songbook is like the Talmud: beyond his own unmistakable originality there lies an extraordinary commentary on the Bible of English Literature—both in the sense of secular literary masterpieces and in using Biblical sources for his own imagery:

And like Pharaoh’s tribe they’ll be drownded in the tide

And like Goliath they’ll be conquered.

(When the Ship Comes In)

There was nothing that he couldn’t pull

I think I’ll call him a bull

(Man Gave Names to All the Animals).

At the end of Tempest he employs William Blake’s hypnotic opening lines from The Tyger to complete his song for John Lennon:

Tyger, tyger burning bright

In the forests of the night

(For a more detailed sampling and analysis of literary sources for Tempest see my review “Bob Dylan and The Great Tradition.”)

The remarkable upsurge of Dylan’s reputation amongst academicians belies the long struggle that preceded it. When he was starting out most academic poets were put off by the use of the term poet to describe him or poetry to describe his songs; indeed one could guarantee a full house in any academic colloquia by merely announcing that reputable academic poets would be considering the question of whether he was a poet at all. The question all but answered itself.

And yet a half century later what was initially a begrudging respect has gradually but resolvedly grown into a profound admiration of how he has mined the great tradition throughout his career, and brought the names and cultural touchstones of our literature into popular music. No wonder they have at long last opened the doors of the American Academy of Arts and Letters to this former college dropout—who from the beginning had opened his doors of perception to them.

This isn’t the first time Dylan has been honored by the academic world; in 1970 he received an Honorary Doctorate from Princeton University, which gave rise to the song Day of the Locusts:

The man standing next to me, his head was exploding

Well, I was prayin’ the pieces wouldn’t fall on me.

Yeah the locusts sang off in the distance

which hearkens back to one of the plagues of Israel. Leave it to Bob to find the dark side of what to most would be an occasion to celebrate—and quickly forget. But Dylan’s song noir—inspired by an army of invading cicadas—makes the ceremony unforgettable:

I put down my robe, picked up my diploma

Took hold of my sweetheart and away we did drive

Straight for the hills, the black hills of Dakota

Sure was glad to get out of there alive.

The second and last time the Poet Laureate of Rock & Roll accepted an Honorary Doctorate was in 2004 at St. Andrews in Edinburgh, Scotland’s oldest university—founded in 1431. Judging from his “graduation picture” it doesn’t look like he would be eager to repeat the experience.

I’m a poet

I know it

I hope I don’t blow it

Dylan said in I Shall Be Free No. 10.

What he didn’t say was that he knew the great poets who came before him—all the way back to the anonymous quatrain that opens many anthologies of English poetry:

Western Wind when wilt thou blow

The small rains down shall rain

Christ that my love were in my arms

And I in my bed again

He calls upon its perfect image of lost love in his 1963 song Tomorrow Is a Long Time:

Yes and only if my own true love were waiting

And if I could hear her heart a softly pounding

Yes and only if she was lying by me

And I lie in my bed once again.

(Its other memorable images found their way into an anonymous cowboy song, Colorado Trail, collected by Carl Sandburg for his book The American Songbag:

Weep all ye little rains

Wail winds wail

All along along along

The Colorado Trail.

And subsequently the Irish poet William Butler Yeats echoed the same line that caught Dylan’s attention:

But O that I was young again and held her in my arms.

America’s current elder statesman of poetry that sings in this tradition, Richard Wilbur, once wrote a brilliant essay that captures this kind of borrowing one poet from another, calling it a “Conversation of Poets,” in which he shows many examples of ways in which poets pay tribute to their forebears while carving out their own road.

Dylan has been a part of this conversation from the beginning.

He transformed the nursery rhyme Who Killed Cock Robin into the protest song Who Killed Davey Moore—a powerful indictment of boxing from the fans to the referee to the sportswriters to the boxer who killed him to the gamblers who profited from it. He recast the Childe Ballad Lord Randall into the antiwar classic A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.

Temporary Like Achilles from Blonde on Blonde goes all the way back to Homer for its title, and I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine from John Wesley Harding finds a place for Christianity’s greatest memoirist in an early portrait of the sacred vs. profane, juxtaposing the world ruled by “kings and queens” against the martyr to self-sacrifice ruled only by Christ. Eleven years before it may well foreshadow Dylan’s conversion to Christianity. But more to the present point it demonstrates that Dylan was able to employ the entire canon of Western literature for his own purposes and broadening vision. To take but one more example, in the previously referenced Highlands from Time Out of Mind he adapts the title from 18th Century Scottish poet Robert Burns, and then quotes it in the song:

My heart’s in the Highlands

No wonder Scotland’s oldest university honored him.

Bob Dylan is America’s greatest songwriter, and he has shown over fifty years that the art of songwriting need take its hat off to nobody—even when that hat is a Huck Finn cap.

Especially so, since Huck’s author Samuel L. Clemens was a founding member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. One might even say—in Dylan’s album title from 1965—that by honoring Dylan they are bringing it all back home.

Yes Bob, Things Have Changed.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com Ross has a PhD in Modern Literature.