Bellydance in Los Angeles

A Brief History

In the beginning, there was The Dance.

Pretty much everyone can get behind that. It’s a good bet that our Paleolithic ancestors cut a groove under the stars. Dig that funky new beat! Ooga’s calling it “rock” music!

OK, that’s just silly. The truth is we haven’t got the slightest idea what dance the first humans did. We don’t even know what sorts of dances were done within great civilizations, like Ancient Egypt, that we know for a fact employed dancers at special events. Archaeologists, historians, artists, and dancers throughout the ages have tried to imagine what the dances of our ancient forebears may have looked like.

Enter the bellydancer.

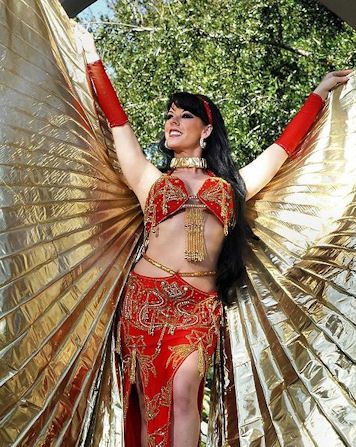

Wings of Isis with Suspira

A staple at weddings, births, and other life-affirming celebrations, the art form commonly known as bellydance goes by many other names, including Oriental Dance, Baladi, and Raqs Sharqi. The term most westerners use to describe the archetypal image of a mysterious Gypsy or harem dancer actually encompasses a multitude of folk dance traditions that have migrated and evolved over time. Today there is scarcely any country where some form of this dance is not performed, whether in public or private, by women and men of all ages, and children, as well.

No one knows where bellydance originated, though numerous countries claim ownership, and theories abound. One of the most commonly circulated stories is that Gypsies, migrating out of India along ancient trade routes, carried their native dance to the Middle East, evolving at every stop as it met and fused with other traditions. Along with spices and brocades the Silk Road brought this dance to Europe. But it wasn’t until 1893, when a young entrepreneur coined the term most people use today, that bellydance took America by storm.

Almeh du Caire (Almeh of Cairo), engraving by Frederic Goupil Fesquet (1806-1893)

When Sol Bloom unveiled his “Algerian Village” attraction at the Chicago World’s Fair, there was initially little interest. The fairgoers were too busy riding the exciting new Ferris Wheel and tasting unusual foods, like hamburgers and cream of wheat, to notice the little corner of the fair set up to look like a dusky foreign marketplace. Desperate to compete with the coin-elongating machines (also new at the fair), Bloom needed to draw attention to his exhibit. At the end of the 19th century, women were still wearing corsets and bustles, and Victorian prudishness dictated that even piano legs should be covered. The dancers were not scantily clad, but unencumbered by corsets, the movements of their torsos could be detected under loose tunics as they undulated. The French called it Danse du Ventre, or “Dance of the Stomach.” Bloom translated this into “Belly Dance,” which sounded so scandalous that everyone simply had to look.

It was the turn of the 20th century, and Americans were feeling restless. Automobiles were becoming affordable and the Auto Club was advertising California as an unspoiled Eden waiting to be populated by upwardly mobile sun worshipers. Hollywood was the new place for artists and spiritual seekers to convene. Movement and dance were adopted in many circles as routes to the Divine. A new craze for the exotic, coupled with the indomitable spirit of the American individual, took the old folk dance in a new direction.

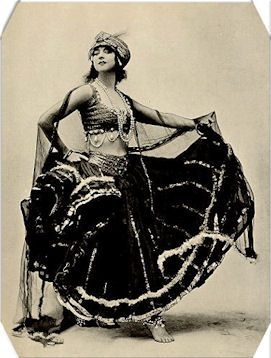

Ruth St. Denis (1879 – 1968)

Ruth St. Denis (1879 – 1968)

One dancer, Ruth St. Denis, while not a bellydancer in the strict sense of the word, was nevertheless influential to the modern conception of Oriental Dance. St. Denis had no formal training, but was brought up in the Vaudeville circuit, where she may have met dancers inspired by or possibly even from Sol Bloom’s show.

Things have changed so much in the last century that it’s easy to forget that only a few generations ago, Orientalism was all the rage in the West. Fine art renderings of harem and slave girl fantasies by earlier European painters who had visited (or read about) the Middle East and North Africa were influential, as was the discovery of King Tut’s tomb. Inspired by an advertisement for cigarettes featuring the Egyptian goddess Isis, St. Denis gave up all other dance forms to focus on creating Oriental dramas with elaborate costumes. She captivated audiences with her fantasy take on Eastern dance, becoming an idol to women in America and Europe who admired her freedom and individuality.

In 1915 St. Denis opened a dance school in Hollywood; two of her students, Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, would become Modern Dance legends. Her work heavily influenced the exotic dance sequences that frequently appeared in Hollywood movies at the peak of the Golden Age of Cinema.

The real and metaphorical Silk Road has never been a one-way street. While dance traditions from the East influenced our artistic development as a nation, innovations in the West changed the face of bellydance in its place of origin. Epic Hollywood pictures inspired an equivalent Golden Age in Cairo, and the glamorous two-piece costume, born in Hollywood, was worn proudly by the most sophisticated Egyptian dancers of the time. Called bedlah, or “suit” in Arabic, this iconic look has become inextricably linked with bellydance throughout the world.

Samia Gamal, Egyptian dancer and film star (1924 – 1994)

Political upheavals affected relations between North America and the Middle East, and the relationship both regions had to bellydance. A wave of Armenian immigrants, seeking refuge from the terrible genocide in Turkey, arrived in Los Angeles. They were soon followed by refugees from around the Levant, peaceful folk trying to escape war. With these groups came the old customs of hospitality and celebrating special events with lively music and dancing. Night clubs sprang up all over town, with names like The Fez, Coco’s, Ali Baba’s, Hadji Baba’s, Grecian Village, and Seventh Veil.

Samia Gamal, Egyptian dancer and film star (1924 – 1994))

Although at first most of the clientele was Arabic, curious Americans would stop in and find themselves entranced by the exotic music and ethereal dancers. Many young women, and a few men, stuck around, encouraged and aided by the dancers and musicians to learn the art form until they were able to go on as performers themselves. For decades these nightclubs were hotbeds of creative cultural interplay, with Greek, Armenian, Turkish, and Lebanese musicians and dancers working together, creating a hybrid form of bellydance, known today as American Cabaret sometimes called AmCab or Classic American bellydance.

Sometime in the late 1950s, a young model and actress named Diane Webber was drawn into the mystique of the Fez, and took lessons from Nadia Simone, an Armenian dancer who grew up in Turkey before moving to Germany, then Los Angeles. Once ready to strike out on her own, and looking for new venues, in addition to Arabic clubs, Webber began performing at Renaissance Faires and teaching classes at a non-profit community adult school called Everywoman’s Village. By this time, the Women’s Lib movement was flourishing, and the school was intended for women whose education had been stalled by marriage or motherhood, offering the chance to take classes that would otherwise have been unavailable to them. Webber, who had learned to bellydance the old way, by observation and imitation, analyzed and codified the dance fundamentals in such a way that even someone without a dance background could understand. Other bellydancers at this time, like Jamila Salimpour in San Francisco, and Morocco in New York, were doing the same thing, systematizing the dance in a uniquely America fashion. Meanwhile in L.A., Webber’s troupe, Perfumes of Araby (after a line from Macbeth) became a popular fixture at local festivals, and many of her students followed in her footsteps to dance at the Arabic nightclubs.

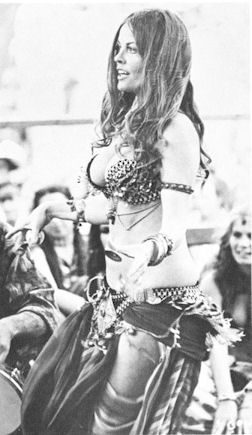

Diane Webber (1932 – 2008)

Unfortunately, world events once again changed the playing field. Driven by politics and drug money, the clubs grew seedy, with the new, younger generation demanding a different kind of entertainment that would set them apart from their Old World parents. One by one, the old nightclubs shut down, or in some cases, like the Seventh Veil, turned into sleazy topless bars, worlds away from the original atmosphere, feeding directly into negative stereotypes of Arabs, that were fomenting in the public consciousness as wars raged overseas.

Diane Webber (1932 – 2008)

Ironically, while attitudes toward bellydancers in the Middle East were becoming increasingly sour, with women there subjected to restrictive laws against public displays of any kind, American women were discovering bellydance as an empowering, feminine mode of creative self-expression and a way to commune with other women. When negative stereotyping by both Arab and American audiences began to affect this newly realized bellydance community, an organization called the Middle Eastern Cabaret Dancers Association (MECDA) was formed, and dancers actually picketed the night clubs in a march for dignity.

In 1979, Diane Webber retired as director of Perfumes of Araby, passing the torch to her star student from Everywoman’s Village. Anaheed, who cut her teeth on the Arabic night club scene, was one of the dancers on the MECDA picket line, and carries on the American Cabaret tradition to this day, a beloved teacher and promoter of bellydance events in the San Fernando Valley. Everywoman’s Village closed in 1999 after a long struggle over finances, but by then there were many other outlets for women to find themselves. New political strife sent an influx of Egyptians to the United States, bringing their own distinctive style of bellydance. The internet also made it possible for dancers on different continents to share information, videos, ideas, and inspirations. Growing cultural sensitivity means dancers today are more aware of differentiations between regions of the world that would have been lumped together by the early Orientalists. Reflecting this change, MECDA rechristened itself the Middle Eastern Culture and Dance Association.

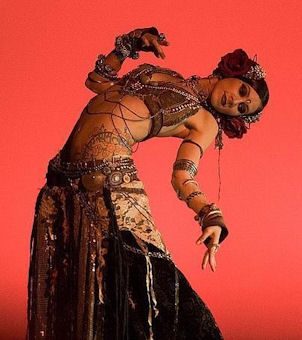

Rachel Brice, American Tribal Fusion

Today, many bellydancers pride themselves on knowing the difference between, say, an Egyptian Saiidi and a Persian Gulf Khaliji, folkloric dances from different countries that both fall under the umbrella of bellydance. At the same time, numerous individuals are creatively fusing Middle Eastern and Classic American bellydance with African, Latin, and South Asian folk dances. The last few decades have seen the rise of a style in this vein that originated in San Francisco with one of Jamila Salimpour’s students, Carolina Nericcio. Called American Tribal Style, or ATS, this form relies on a standardized movement vocabulary and focuses on group improvisation. This style in turn has spawned another contemporary movement called American Tribal Fusion, exemplified by world-famous dancer Rachel Brice. Tribal Fusion draws from a similar costume and movement vocabulary to ATS but with an emphasis on individual expression and sharply defined body isolations. With so many styles to choose from, one thing is clear: the American tradition of bellydance is here to stay, and will continue to evolve as dancers carry the old art into the 21st century.

Interested in checking out the diversity of bellydance in L.A?

Here are some upcoming events to get you started!

Holiday Hafla to benefit the launch of Los Angeles MECDA

Saturday, December 3, 2011 6:00pm – 10:00pm

Sabor Y Cultura Cafe

5625 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood CA 90028

Dancers, Troupes, Henna & Tarot card reading

“Project Dream” accepting new or like-new stuffed animals and blankets

323-662-9332 lamecda@gmail.com

Ya Harissa Bellydance Theatre

Sunday, December 4, 2011 7:30pm – 9:30pm

The Talking Stick

1411 Lincoln Blvd., Venice, CA 90291

310-450-6052

Twelve dancers performing dances from the Middle East and North Africa.

No cover charge.

Tribal Fusion Faire VIII

December 10th – 11th, 2011

Saturday 10am – 11pm

Sunday 10am – 7pm

San Luis Obispo Veterans Memorial Building

801 Grand Ave., San Luis Obispo, CA

Celebrating All Tribes with Dance, Music, Food, & Shopping

Holiday Party with Mesmera!

Sunday, December 11, 2011

3:00pm – 6:00pm

Studio A Dance

2306 Hyperion, Los Angeles, CA 90027

Teacher/student performances

Live drumming, open dancing, refreshments

$8 at the door

Anaheed and Anja’s Holiday Dance Party

Sunday, December 11, 2011 7:00pm – 9:00pm

Granada Pavilion

11128 Balboa Blvd., Granada Hills, CA 91344

Live music, open dancing, and light refreshments.

$18 advance, $23 at door

For more information call Anaheed 818-893-9019 or Anja 818-389-5279

Tonya’s Annual Spirit of Christmas Extravaganza and Annual BDCU “Mega Stars of the Universe” Show

December 14, 2011 7:00 – 11:00 pm

Khoury’s Restaurant

110 N Marina Dr., Long Beach, CA 90803

$20 admission plus 2 drink minimum or $10 food purchase

Contact: Atlantis 562-433-6615

Club Cleopatra

Sunday, December 18, 2011 6:00 – 8:00 pm

El Baron Restaurant

8641 W. Washington Blvd.

Culver City, CA, 90232

Belly dance performances every 3rd SUNDAY of the month

$10 cover

310-210-5664

www.facebook.com/pages/Culver-City-CA/Club-Cleopatra

Winter Fiesta and Pot Luck at DanceGarden

Sunday December 18, 2011

Doors at 3:00pm, Show at 3:30pm

DanceGardenLA

3407 Glendale Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90039

Performances by DanceGarden teachers, students and more!

DJ Sets by Petrol Bomb Samosa and Raffles for FREE CLASSES!

No cover, but please bring a dish or beverage to share

323-660-4556 jenna@beyondbellydance.com

New Year’s Party and Open House at the Los Angeles Bellydance Academy!

Wednesday December 28th Doors open at 6:30pm, Show starts at 7:00pm

8503 Pickford St., Los Angeles CA 90035

Student/teacher showcase

Raffle for FREE CLASSES!

Swap Meet

THE PARTY IS FREE, so bring your friends and family and LET’S DANCE!

310-854-3500

http://labellydanceacademy.com/

Zarina Silverman is an artist and native of Los Angeles who was bitten by the bellydance bug in 2002 and has been shimmying ever since. She will be performing in the American Cabaret style to live music at Anaheed and Anja’s Holiday Party in Granada Hills on December 11. Many thanks to Anaheed for sharing her firsthand account of the rise and fall of the Arabic club scene in Los Angeles.

Bellydance in Los Angeles

A Brief History