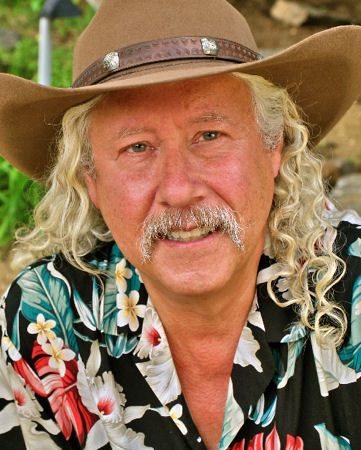

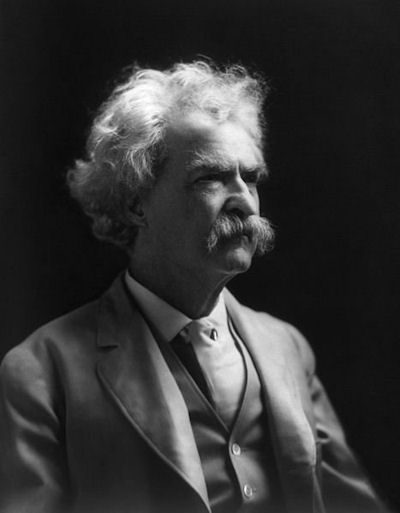

Mark Twain with a Guitar: Arlo

I don’t know what the Kennedy Center is waiting for. Thirteen years into awarding the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, they have yet to land on America’s greatest living storyteller—now that Utah Phillips is gone—that would be Arlo Guthrie, who might best be described as Mark Twain with a guitar. Since crafting Alice’s Restaurant in 1967—his classic 18 minute 34 second Thanksgiving perennial antiwar satire, Arlo has kept Woody Guthrie’s flame alive and then some, by being a constant voice for the voiceless, and the inheritor and greatest practitioner of a vein of humor that traces its roots back to Mark Twain, through Will Rogers, Woody Guthrie, Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Dick Gregory and U. Utah Phillips, the Golden Voice of the Great Southwest.

I don’t know what the Kennedy Center is waiting for. Thirteen years into awarding the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, they have yet to land on America’s greatest living storyteller—now that Utah Phillips is gone—that would be Arlo Guthrie, who might best be described as Mark Twain with a guitar. Since crafting Alice’s Restaurant in 1967—his classic 18 minute 34 second Thanksgiving perennial antiwar satire, Arlo has kept Woody Guthrie’s flame alive and then some, by being a constant voice for the voiceless, and the inheritor and greatest practitioner of a vein of humor that traces its roots back to Mark Twain, through Will Rogers, Woody Guthrie, Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Dick Gregory and U. Utah Phillips, the Golden Voice of the Great Southwest.

And Arlo does it all with a guitar, building his cante-fables into songs that charm musically as well as display their extraordinary imaginative range and daring. His story songs address the challenge of being under FBI surveillance, the fruit of having been the voice of the counterculture since Woodstock, under the watchful eye of US Customs agents and the DEA; the result of his hit song Coming Into Los Angeles, announcing his suitcase was filled with marijuana; and even gaining the scrutiny of the Department of Weights and Measures, when he refused to convert to the metric system since it would undermine his performance of David Mallet’s The Garden Song—arguing that we have to get out of our problems the same way we got into them—“inch by inch, and row by row.”

Nor can Arlo even take such a neutral institution as the US Post Office for granted—not since his memorable appearance in the Washington DC branch, to cut the ribbon on the first-class Woody Guthrie postage stamp; commented Arlo, in full view of the Postmaster General and beneath the icy glares of America’s Ten Most Wanted—“We weren’t surprised to see our father’s picture hanging in the post office—we were only surprised that you had to pay money to get it.”

One by one, Arlo has challenged the authorities and invited the prying eyes of virtually every agency of the US Government—none more so than the very first one he challenged—that would, of course, be the Draft Board—the setting of his unlikely 1967 hit, Alice’s Restaurant—where he succeeded in flunking his psychiatric exam by insisting that above all, he wanted “to kill, to see blood and gore hanging from their teeth.”

It’s one thing to be a folk singer identified with such important but warm and fuzzy causes as the environment (John Denver), the farmer (Willie Nelson) and the memory of 9/11 (Tom Paxton, for The Bravest, and Bruce Springsteen, for The Rising).

It’s quite another to carry the banner for draft resisters, pot smokers (before medical marijuana began to win mainstream acceptance), outlaws (for continuing to sing Pretty Boy Floyd), the American labor movement (by carrying on The Ballad of Harry Bridges), and not just iconic heartland small farmers, but the hard-traveling Chicano migrant farm-workers—who still respond to Arlo’s singing the old man’s Deportee (with music by Martin Hoffman)—with the still provocative and telling lines:

Some of us are illegal and others not wanted

Our work contract’s out and we have to move on

Six-hundred miles to that Mexican border

They chase us like rustlers, like outlaws, like thieves.

In today’s political climate, where the entire debate has shifted ten degrees to the right of center, it takes considerable chutzpah to stand up for the disenfranchised immigrant worker, the antiwar activist, the aging hippie, and the troubadour who once observed, “some will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen.”

Arlo Guthrie is still blowing down that old dusty road pioneered by his father Woody, and still able to puncture stuffed shirts and deflate the pretensions of the mighty with a song and satire worthy of the architect of American humor—Mark Twain.

And somehow, in the midst of his impeccable 1960s longhair road warrior credentials, he has built a body of work unrivalled for its profound embodiment of America’s core values. With his hit song—Steve Goodman’s City of New Orleans—Arlo became the musical conscience of some of Katrina’s hardest hit residents—New Orleans’ musicians, whose instruments were destroyed by the hurricane. It was Arlo Guthrie who imagined and led a whistle-stop tour on the specially chartered train to raise money throughout the fabled former run from Kankakee, Illinois to New Orleans, Louisiana, to restore the dignity and ability to earn a living of their great jazz musicians who have been the true voice of America at home and abroad—ever since Louis Armstrong first picked up a trumpet on Basin Street.

It was Arlo’s tour—with the help of the likes of comedian Richard Pryor—noto bene the first recipient of the Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for American Humor—that put these trumpets and clarinets and slide trombones back into the hands of our ambassadors of goodwill. Not to put too fine a point on it—this Brooklyn-born (“with a guitar in one hand, and a harmonica in the other”), Washington, Massachusetts’ folk singer and storyteller helped bring Mardi Gras back to New Orleans. If that doesn’t deserve a prize, I don’t know what does.

And yet, that only begins to sum up Arlo’s concerns as an artist—his world view reaches beyond our shores; one of his most moving songs is the musical setting he created for English poet Adrian Mitchell’s poem Victor Jara, written in memory of the Chilean folk singer tortured and murdered by General Augusto Pinochet, with the help of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and our own CIA. Arlo was a major part of the legendary Phil Ochs’ concert to benefit Chilean refugees in 1973—after the overthrow of socialist Salvadore Allende and the murder of 3,000 students and workers in their national soccer stadium—Estadio Chile—which now bears the name of Victor Jara, whose hands were smashed by the military junta in full view of the doomed protesters imprisoned in the stadium.

Arlo and Adrian Mitchell’s song was the most moving testament to folk music’s ability to speak truth to power, “His hands were gentle/His hands were strong.” Arlo’s mission as an artist has always been to oppose unjust authority, to celebrate individual freedom and social equality, and to preserve the best of the past through its music and wit.

The tour that now brings him to UCLA’s Royce Hall for the second time in two years is called simply “Journey On.” It’s heartwarming that there seem to be no plans for a “last farewell tour,” since we need Arlo now more than ever. With so many faux patriots cluttering up the political landscape, how inspiring it is to be able to hear the real thing—a musician whose love for both the land and her people transcends the gaudy flag-waving jingoism of opportunists, but who seems always to be close by or ready to hop a train when hard times demand it.

When he first broke onto the folk scene in 1967, two years after Dylan declared, “It’s all over now, Baby Blue,” Guthrie seemed to be a most unlikely torch bearer for his father’s legacy; he was clearly no Pete Seeger in waiting, but an authentic anarchist and fabulist of this tallest of tall tales—the amazing story song Alice’s Restaurant that told how he succeeded in being thrown out by his draft board for being too crazy for the military.

We no longer have a draft, but we are still engaged in dubious battle in two countries with one in the wings—and Arlo’s song is still a timely reminder of the huge distance between those who get us into wars and those who must risk and too often lose their lives in fighting them.

And yet, as a humanist humorist, Arlo has found new ways to keep his signature tale from becoming an old chestnut only to drag out once a year on Thanksgiving. He was startled one day to be told by an observant friend that he might be able to solve one of the lingering mysteries of the modern era—what was cut out of Nixon’s Watergate tapes—the famed eighteen and a half minutes that has never been accounted for, but which could reveal what Nixon was terrified of being discovered by Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox. After all, wondered Arlo, how many things are exactly 18 minutes 34 seconds long?

When Arlo first performed it in public, at Gerde’s Folk City in 1967, his mother Marjorie Mazia Guthrie was one of only 12 members in the audience who came out to hear him. Other mothers might have looked around at the mostly empty house and been discouraged—and passed that discouragement onto her son, but not Marjorie. To the contrary, her optimistic take on the situation was that her son had 12 disciples—the same number Jesus had when he started out—and this from a Jewish mother. They were right on track.

That same year, 1967, saw the publication of Hard-Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People, with many of Woody’s hardest-hitting Dust Bowl Ballads, and his extraordinary head-notes to all the songs in the book—from the likes of Aunt Molly Jackson (I Am a Union Woman), Sarah Ogan Gunning (I Hate the Capitalist System), Jim Garland (I Don’t Want Your Millions, Mister) and Ella May Wiggans (The Mill Mother’s Lament). It remains one of the most useful reference books I own.

Many years in the making, this Oak Publication finally saw the light of day none too soon, for Woody Guthrie died that same year, October 3, 1967, at 55, after suffering for 17 years with Huntington’s Chorea, the genetically inherited degenerative illness that also took the life of Woody’s mother and four of his children by his first wife, Mary. Fortunately for Arlo, for his children and, need I say it, his country, Arlo, apparently along with his full siblings Nora and Joady, dodged the genetic bullet—which would mean that it is gone from future generations of their descendants as well.

But living in the shadow of death for a good part of his adult life must surely have colored both Arlo’s innate seriousness as an artist, his deft comic touch and timing, and his depth of humor that addresses the sometime darkness of the human condition without flinching from tragedy or retreating from his clear embrace of the human comedy.

That rare balancing act, in which he both carries on the best of the past, and continues to champion his father’s hard-hitting songs for hard-hit people, while using his uncanny gifts as a storyteller, raconteur, and songwriter himself to entertain as much as he enlightens and inspires, has endeared him to a grateful folk music audience for going on 45 years.

What a remarkable stroke of good luck to have inherited his father’s genius and dodged his father’s family curse; and what extraordinary good fortune that we still have him around to enjoy, having grown from a daring young man on the flying trapeze to the heir apparent of the grand old man of American folk music (Pete Seeger, of course, who turns 92 this May 3rd).

Arlo can’t string three words together without making you laugh, and like Mark Twain, who specifically opposed US intervention in the Phillipines during the Spanish-American War and our propensity towards imperialism in general, he took to heart John Quincy Adams quixotic warning, “America does not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.”

Not when we have so many dragons right here at home that need slaying. If Mark Twain had “a pen warmed-up in Hell,” Arlo has maintained a lighter touch, but he has never sacrificed being a truth teller for popular acclaim. At 63 he remains an outsider, a rebel, albeit a rebel with a cause.

Like Twain’s greatest creation, another outsider and rebel, Huck Finn, his Aunt Sally was going to adopt him and civilize him, but he couldn’t stand it. Huck never had to grow up; Arlo did, but he never gets old. So once again he is about to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, guitar in hand and Moose (poem) in tow.

He’s been on that road for forty-five years, and has yet to host Saturday Night Live, the Oscars, star in a sitcom, or appear in a movie as anyone other than himself, the sine qua non of attracting the attention of the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor Committee.

And yet, for some strange reason, when the Berlin Wall came tumbling down in 1989, who did the German people call upon to be with them, talk to them, sing to them and celebrate with them? Guess what: it wasn’t Richard Pryor (1998), Jonathan Winters (1999), Carl Reiner (2000), Whoopi Goldberg (2001), Bob Newhart (2002), Lily Tomlin (2003), Lorne Michaels (2004), Steve Martin (2005), Neil Simon (2006), Billy Crystal (2007), George Carlin (2008), Bill Cosby (2009), or the 2010 winner, Tina Fey.

It was Pete and Arlo—having led the fight for freedom and justice for so long in their own country, Germans understood that they were the ones to stand in front of that crumbling Wall and serenade their newly won freedom.

How could the German people get it so right, and the Kennedy Center so wrong? I am not sure, but offhand I can think of no American author who would better appreciate the delicious irony in the situation—than the one who used humor as a weapon against slavery and war in his own time, and who would surely honor a performer who uses it as a weapon for peace and freedom now.

They don’t call it the Mark Twain Prize for nothing. If Arlo doesn’t deserve it, nobody does. And if not now, when?

Arlo Guthrie, with Abe Guthrie and the Burns Sisters, will be at UCLA’s Royce Hall on Friday, April 8 th at 8:00pm and FOX Performing Arts Center in Riverside on Sunday, April 10th at 7:30pm. Tickets available through Ticketmaster or at the respective Box Offices: UCLALive! and FOX PAC. Additional Woody related activities happen in the Inland Empire that weekend. Check out L.A. Acoustic Music Festival for more information.

N.B.: The Kennedy Center honored Pete Seeger in 1994 as a performing artist. No one would mistake Pete for a humorist; in concert he has often played straight man to Arlo.

Ross Altman may be reached at greygoosemusic@aol.com Ross will perform at the Earth and Arbor Day Festival in Santa Clarita’s Central Park, Saturday, April 16 at 3:00pm; and at the Roots Fest on Adams in San Diego, Saturday, April 30, 2011.