ANGEL LUÍS FIGUEROA: THE MUSIC OF SANTERÍA

Angel Luís Figueroa: The music of Santería

10/05/2014

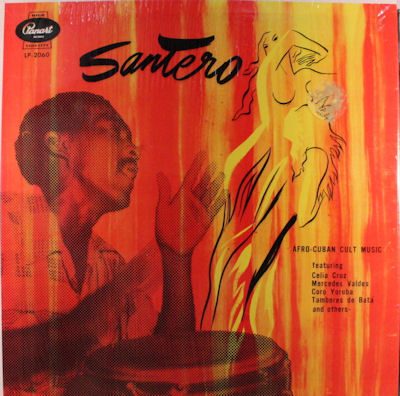

Shuffling through a record bin last month, an LP titled Santero from the famed Cuban label Panart caught my attention. The cover is beautiful but a little strange. Set against a fiery background, a conga player is frozen mid strike while a wraith of a beautiful woman billows like smoke from the drum, poised as if waking from a long sleep. In the liner notes, the writer claims it to be the first ever commercially recorded Afro-Cuban “cult music.” The strange track titles – Changó, Babalú Aye, Yemayá, Ochún, Obatalá, Eleggua – I recognized as the names of Santerían deities.

Shuffling through a record bin last month, an LP titled Santero from the famed Cuban label Panart caught my attention. The cover is beautiful but a little strange. Set against a fiery background, a conga player is frozen mid strike while a wraith of a beautiful woman billows like smoke from the drum, poised as if waking from a long sleep. In the liner notes, the writer claims it to be the first ever commercially recorded Afro-Cuban “cult music.” The strange track titles – Changó, Babalú Aye, Yemayá, Ochún, Obatalá, Eleggua – I recognized as the names of Santerían deities.

It was not the kind of record I would have expected to resurface in a new-age vinyl shop, but I was pleased to find it having taken a semester of percussion lessons. My teacher was the renowned Afro-Cuban percussionist, Angel Luís Figueroa, who has for the past decade, endeavored to make the music and philosophy of Santería accessible to all.

At my first lesson I remember entering the practice room and seeing Angel seated on the piano bench examining my paperwork. Salt and pepper hair, neatly trimmed facial hair and a persona that exuded youthful energy, he greeted me with candor (“Your last name is chicle? What kind of a last name is gum?”) He impressed upon me a desire to wear suave shoes, flirt excessively and sashay to the rhythm of I-yam-da-sheeit. In short, I immediately liked him.

Only the colored beads around his neck would have suggested that he was in fact a priest in an arcane religion and a master of a musical tradition that predated western history.

Angel runs Paws Music, an organization dedicated to the pedagogy of Afro-Cuban percussion, from his mid-town studio where Cochran Ave. meets Pico Blvd. Before he started teaching tykes the rumba clave, however, Angel was a child prodigy who taught himself to play on kitchen pots and pans. Now a prominent performer of bongos, congas, batá, and timbales, he has collaborated and toured with the likes of Herbie Hancock, Mongo Santamaría, The Temptations, and Celia Cruz. After mastering salsa and rumba music, he traced the roots of his influences back to Africa via the Caribbean practice of Santería.

The roots of Santería, known officially as La Regla Lucumí, existed long before the slave trade. When traders took the Yoruba people of West Africa to Cuba, in an effort to resist Spanish Catholicism, they strengthened their native beliefs and developed a new synthesis, which became the model for Santería today. Intricate drumming patterns, played on the batá drums, serve as a form of worship and a means to communicate with deities or orishas as they are called in the practice.

After stumbling across the Santero record, I decided to check in with Angel. It had been four years since I had last seen him, but driving west on Pico Blvd., I remembered the exact kamikaze turn into the narrow, nearly invisible driveway.

From the shade of the studio door, Angel greeted me with a pound hug (he grasped my hand as if preparing to arm-wrestle and pulled me into a hug) and ushered me inside whereupon we immediately began discussing both the pragmatic and cosmic elements of Santería. Santeros are the priests of the religion, but Angel doesn’t preach from a pulpit. Instead, his teaching space is a cozy, wood paneled recording studio adorned with every conceivable kind of percussion instrument.

Music functions heavily in Santerían rituals. “Sometimes I’m playing and my eyes roll to the back of my head. We’re in a ceremony, Santo has just come down and I can feel the energy; my hairs are all standing up. I’m in this trance and I’m sweating like a pig and I have three or four hundred dollars on my forehead.” (During the fervor of a ceremony – a toque – participants will sometimes slap money on the drummer’s perspiring forehead.) “If it sticks to you, then you get to keep it. If it falls to the floor, you’re not sweating enough and they take it back. The religion is beautiful, man.”

I imagined what the neighbors would think, looking over the fence to observe a ceremony such as this.

Batá music is played with three drums – the okónkolo, iyá and itótole – each with their own role. Okónkolo is the smallest and keeps time with short repeating patterns; the iyá is the large, master drum responsible for leading the rhythms and improvising; the itótole, a medium-sized drum, colors the texture by playing rhythmic counterpoint with the okónkolo or by entering into dialogues with the iyá. All the music is played from memory, but no performance is ever the same. The okónkolo and itótole players need listen carefully because the position of the iyá player can be capricious; he will look to change patterns and cycles at a moment’s notice in order to keep the two other drummers on their toes.

Batá music is played with three drums – the okónkolo, iyá and itótole – each with their own role. Okónkolo is the smallest and keeps time with short repeating patterns; the iyá is the large, master drum responsible for leading the rhythms and improvising; the itótole, a medium-sized drum, colors the texture by playing rhythmic counterpoint with the okónkolo or by entering into dialogues with the iyá. All the music is played from memory, but no performance is ever the same. The okónkolo and itótole players need listen carefully because the position of the iyá player can be capricious; he will look to change patterns and cycles at a moment’s notice in order to keep the two other drummers on their toes.

There are two main musical ceremonies in the tradition. The toque is a secular celebration with drumming, singing and dancing. The other is a sacred ceremony called the igbodu where the rhythms of each orisha are represented as a unified, musical whole. “The igbodu is seco,” Angel elaborated, “because it has no words and lasts exactly one hour, from noon to 1pm. It is a time to honor the tradition and feel connected to the past.” In a seamless display of interlocking rhythms, the three drums perform the igbodu for a silent gathering of priests.

Not without dogmas, many sects of Santería exclude women from performing on the drums. Angel explained, “Inside of the drum lives a goddess. She’s angry because she was trapped in the drum and must live there for eternity. The only kind of energy that can appease her anger is male energy.” I knew already that, contrary to most proponents, Angel asserts his belief in teaching Santerían music to both genders. At times, his efforts to make the practice less rigid have compromised his position within the community of santeros, but his resolve remains firm. “No batalero should ever, ever have disdain for women, because in Santeria the women are gods.”

Two of his students, Danny Alfaro and Thaddeus Gallizzi arrived at the studio, dressed from head to toe in white. It is common practice at a toque that the performers wear white as a gesture of purity and a means to attract positive energy. After some debate as to whether or not Thaddeus’ shoes were white enough, the trio was soon seated and ready to play, the hourglass-shaped drums on their laps. Angel announced themselves as Los Tres Caballeros, and quickly refreshed his students on the piece they were about to perform.

Angel has to be creative in order to teach the music because it can’t effectively be contained by western notation. Using onomatopoetic syllables, he teaches a few bars at a time to individual drummers and then teaches where that pattern aligns within the larger context of the rhythm. Angel corrected the itótole player saying, “No, no your response is: ki ki bumboom. Ki ki!” The student listened intently.

Angel has to be creative in order to teach the music because it can’t effectively be contained by western notation. Using onomatopoetic syllables, he teaches a few bars at a time to individual drummers and then teaches where that pattern aligns within the larger context of the rhythm. Angel corrected the itótole player saying, “No, no your response is: ki ki bumboom. Ki ki!” The student listened intently.

“It’s in my DNA somehow by virtue of my Nicaraguan heritage and growing up in the Mission District of San Francisco,” said student Danny Alfaro. The music rekindled an interest in his heritage and inspired the desire for a deeper understanding of music and philosophy. “The music mesmerizes me just because of the random or chaotic feeling in the rhythm and the fixed or stable feeling in the voices. It’s a very interesting and powerful effect.”

Adjusting the drum in his lap, Angel shook the bells clinging to the iyá and slapped the large end twice – a signal to the other players to shut up. They would play the Chachalakpafún rhythm to honor Yemayá, the mother of all living things.

Batá rhythms are not in any way equivalent to the sacred music of the west. Instead of being pure and gentle, they are intense and visceral. They resonate with our instincts more than our feelings, resulting in profound emotions and subconscious connections. When they played, I sat in front of the drums, hearing the pointillist melodies ripple across the synchronized drumheads. To me, hearing the mesmerizing patterns and the rhythmic figures morph into each other I imagine something like the sonic equivalent of the aurora borealis.

“You have to think about the rhythms the same as everything else in the universe.” Angel said, commenting on the complex, orbital nature of the rhythms. “The galaxy is also falling through space because the inner engine of the galaxy is pulling all these things around it. The batá is our rhythmic interpretation of that. The rhythms fall into the future much in the same way that the sun falls around the black hole and the planets revolve around the sun.”

Angel confided, “I came to the religion as a scientist. But I asked myself, is the universe expanding? Yes. These people (the Yorubas) said it was expanding three thousand years ago.” He drummed his fingers on the chair and smiled, “Don’t get me wrong though I still love Edwin Hubble.”

I found it odd but somehow natural that the dichotomy between religion and science should come together in so casual an environment. Suddenly, the hum of traffic outside and the burbling water dispenser all seemed like an integral part of our discussion. In the same way that the batá drums remain synchronized despite rarely playing in the same time signature, Angel sees all things as interconnected.

I wanted to ask him to elaborate, but couldn’t quite find the right words. He answered my unasked question perfectly saying, “That’s just the polymeter of the universe.”

I want to thank Angel Luis Figueroa for making himself available to my wide-eyed questions and for being an incredible resource to all who are interested in the tradition. Check the links to find out what’s new with Angel Figueroa and Los Tres Caballeros.

Jonathan Shifflett is a recent graduate of USC’s classical guitar program, who has since seen the light and traded the guitar for a banjo. When not tracking down train car murals or searching for hobo hieroglyphics, he enjoys pretending to play the fiddle and thinking about the folk music world at large.